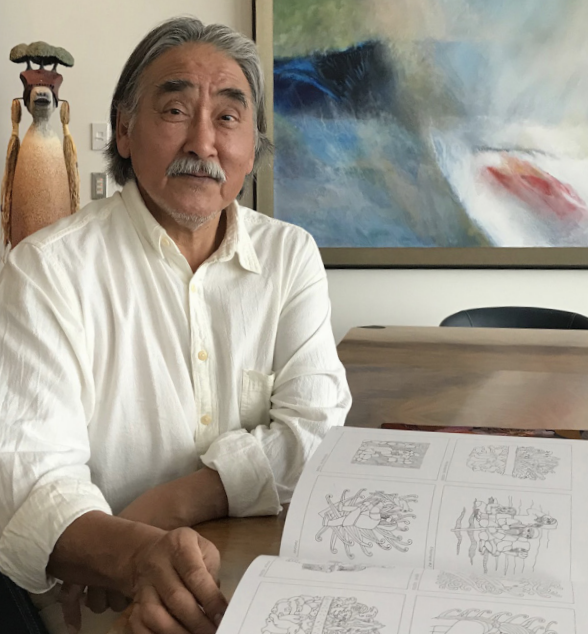

Connecting with the past—Artist Abraham Anghik Ruben reflects on art & ancestry

The Winnipeg Art Gallery–Qaumajuq has launched a solo exhibition highlighting the work of Inuvialuit artist Abraham Anghik Ruben and his 50-year career.

The show features more than 100 of his works, many of which are being shown publicly for the first time. Ruben said stepping into the Qilak Gallery to see the installation was a special moment.

“I walked into the hall and I was quite blown away,” he told Eye on the Arctic in a telephone interview. “It’s an immense 8,000-square-foot space with 30-foot-high ceilings and natural light from glass domes above. I told the director years ago, ‘No problem—I can fill it.’ And we did.”

This is Ruben’s first major show at the gallery since 2001.

The works on view span his career—from early stone carvings to recent paintings begun during the COVID-19 pandemic. The exhibition is co-curated by Inuk artist Heather Campbell and WAG-Qaumajuq curator Darlene Coward Wight, and it is the first to be mounted in the Qilak Gallery, Qaumajuq’s largest space dedicated to Inuit art. The show runs until spring 2026.

Many of Ruben’s pieces explore the interactions between Inuit and Nordic peoples and the spiritual connections between the two cultures.

“Since about 2004, I’ve been exploring the contact between the Vikings and the Inuit,” Ruben said.

“There’s very little written evidence, but there’s so much physical evidence—narwhal tusks, walrus hides, even live polar bears—that points to extensive trade. That kind of exchange doesn’t happen in open warfare. There had to be cooperation.”

Ruben said he’s hard pressed to choose a favourite work in the show.

“Every piece needs to be able to stand on its own,” he said.

“I’ve infused these works with physical, intellectual, emotional, cultural, and spiritual elements. It’s my way of honouring my elders, my parents, my early teachers—people who gave me a way to look at the world.”

Connecting with the past

Ruben was born in 1951 near Paulatuk in the Northwest Territories. His work has been shown internationally including the Smithsonian and the Louvre. He was appointed to the Order of Canada in 2016 for his contributions to art and Indigenous cultural preservation.

Now based on Salt Spring Island, BC, Ruben lives on a 10-acre farm with his wife, where they grow much of their own food. He says the landscape of the island has shaped his work just as profoundly as his Arctic roots.

“We live 1,200 feet up, facing east,” he said. “We can see Mount Baker, the mountains above Vancouver… and it’s the only place in Canada where I can work outside year-round.”

Asked what he hopes visitors take from the exhibition, Ruben said he hopes people can reflect on what it means to live and thrive in a rapidly changing world.

“I’d like people to walk away with some connection to the past,” he said. “I’m honouring both the Inuit and the Norse—two peoples who understood the spirit of place, who passed down tools for survival, and who taught us to be just plain good human beings. [Because today] we seem to have lost our way.”

When it comes to advice for artists hoping to follow in his footsteps, he said the most important thing is humility and trusting your instincts, something he learned early.

At 19, Ruben followed his instincts off a tour bus in Fairbanks, Alaska, and convinced master artist Ronald Senungetuk to take him on, despite having no formal training.

“He gave me two weeks to prove myself,” Ruben said. “I came back with sketches, and he told me, ‘I’ve never seen such a load of crap in my life—but you made the effort. That’ll do. Your classes start tomorrow.’”

It’s a lesson that Ruben said has stayed with him ever since.

“Follow your heart,” he said. “Follow your intuition.”

Comments, tips or story ideas? Contact Eilís at eilis.quinn(at)cbc.ca

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: Connecting through culture—How Isaruit became a haven for Ottawa Inuit, Eye on the Arctic

Finland: Sami joik, symphonic music fusion from Finland makes int’l debut in Ottawa, Eye on the Arctic

United States: How Inuit culture helped unlock power of classical score for Inupiaq violinist, Eye on the Arctic