The Supreme Court of Canada has rejected the request of a convicted drug smuggler to return to Canada to serve out the remainder of his sentence. The high court upheld the right of the public safety minister to refuse requests from Canadians imprisoned abroad to return to serve the rest of their sentences at home.

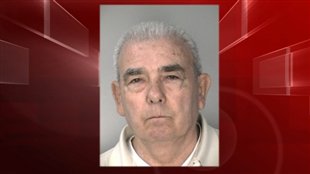

Pierino Divito, 75, pleaded guilty to cocaine possession and intent to distribute and was serving a seven-and-a-half-year sentence in Texas.In 2006, he requested a transfer back to Canada to serve the remainder of his American sentence at home. The U.S. agreed, but the Canadian government refused twice. Divito appealed to the courts.

Canada has “transfer of offenders treaties” with many other countries that allow for this kind of exchange of prisoners and previous governments have allowed prisoners to return. But the current administration has mostly refused such requests.

Decision preserves minister “virtually unaccountable discretion”

“…(this decision) affirms a wide and virtually unaccountable discretion on the part of the minister to reject applications for prisoner transfer,” says Audrey Macklin, professor and chair in human rights law at the University of Toronto. In what she calls its “opaque” decision, she notes the court did leave space to review individual decisions but says that is a process that is much narrower and less accessible.

“The starting point, (that) the minister has wide discretion, seems to be preserved,” says Macklin. “Since this government has used its wide discretion to reject virtually all applications that come before it, there’s reason to think that they will feel emboldened to continue in that practice. And it will be difficult but not impossible for individuals subject to it to mount a challenge.”

Decision may compromise inmate exchanges

Prisoner exchange agreements depend on reciprocity, she adds. And while some may think Canada wins by not accepting the return of Canadian inmates, she thinks it’s just a matter of time before other governments refuse the return of their own prisoners.

Refusal means inmates are not supervised

Accepting the return of Canadian inmate to serve time at home means the government can supervise rehabilitation and the reintegration into society at the end of a sentence, Macklin points out. She thinks it is of less benefit to society to have someone finish their term abroad and then return to Canadians society with no supervision.

The Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms (section 6) assures the right of citizens to enter and remain in Canada. But some of the judges agreed the violation of that right is justified if inmates pose a danger to Canadians while they are in a Canadian prison. The Canadian government had argued Divito might get involved in organized crime. That, says Macklin, raises questions about the kind of job the corrections service is doing in running Canadian prisons.

For reasons beyond our control, and for an undetermined period of time, our comment section is now closed. However, our social networks remain open to your contributions.