No, it’s not a new food recipe, its about how food is digested.

A Canadian research team has made a breakthrough in discovering how the digestive system works. It has been something that has eluded scientists for years, mostly because they were looking at the wrong thing.

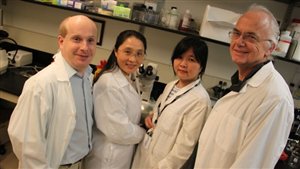

Dr Jan Huizinga of McMaster University in Hamilton, Ontario lead the research team.

Scientists have puzzled over bowel movement ever since the discovered the intestines nutrient absorbing function in the 19th century.

The new discovery hinges on a particular type of cell and its network, which are called “interstitial cells of Cajal”, named after the scientist who first discovered them.

Also known as “pacemakers” the network of cells send regular signals to muscles in the intestines to contract. There are two sets of the pacemakers, the first set is controlled by the nervous system and the researchers discovered the second set is activated by the nutrients in food in the gut.

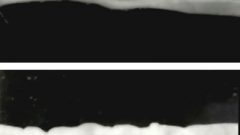

The top photo shows a rat’s gut undergoing propulsion, the motion of pushing content down the intestine in a relatively linear fashion. The buttom photo shows segmentation, the wax and waning of the intestine that allows nutrients in the food to the absorbed. (Supplied by Jan Huizinga)

This second set is where the research team made its discovery, having previously been looking incorrectly at the nervous system as the activator for the “checkered pattern” of muscle contraction.

When they used a nerve blocker to block all the nervous system, the segmentation activity in intestine continued.

“Then we saw beautiful segmentation motor pattern and we said, ‘Look at this. This can happen without any interference of the nerve system.’ So then we changed all of our hypotheses. We changed all of our protocols, all of our project objectives,” he said.

While the first set pushes food along the intestine, like squeezing a toothpaste tube, the second set causes a different muscle contraction holding the food and mixing it, a “segmentation” of the intestine

The pacemaker cells are scientifically known as !CC-MP (myenteric plexus) for the first set of propulsion triggers, and the second set are known as ICC-DMP (deep myenteric plexus)

Dr. Jan Huizinga, says without the second set of pacemakers, the food would simply be pushed too quickly through the intestine. He says “the second pacemaker is absolutely essential otherwise we wouldn’t be able to absorb the nutrients”. It’s the action of the two sets of pacemaker actions that cause a rhtymic motor activity in the gut.

Because segmentation activity had been poorly understood, there had been few treatments for conditions like constipation, diarrhea, bloating and malabsorption of nutrients.

The next step for Professor Huizinga and his team is to further study the second pacemaker, ICC-DMP, to come up with a treatment for such problems by modifying segmentation activities.

Dr. Huizinga said collaborating with experts from different fields has been key to the study. For example, to understand how the two pacemaker networks communicate with each other, Huizinga worked with engineers from the University of Toronto. A mathematician from the University of Manitoba and clinicians from Wuhan University in China also took part in the study.

The study was published in science journal Nature Communications on Monday (abstract here)

For reasons beyond our control, and for an undetermined period of time, our comment section is now closed. However, our social networks remain open to your contributions.