Indigenous peoples and cultures in Canada are undergoing a renaissance in the wake of the national Truth and Reconciliation Commission, and a new giant map that charts the places and spaces before European contact, is providing a greater visual and historic context.

“There’s so much to learn in this one little spot, because it’s so different.”

The TRC investigated the Residential School System that was in effect in from 1870 to 1990 across the country.

It forced indigenous children from the age of 7 to 15, into schools, generally far from their homes.

The experience for many children, of extreme abuse, and the banning of their languages and shaming their cultures, left a legacy of pain and social disruption that is only beginning to be addressed in this new millenium.

The TRC culminated in 94 Calls to Action, and slowly but steadily the greater Canadian society is responding.

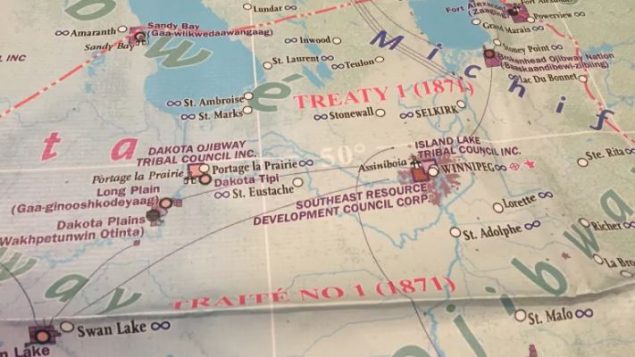

Canadian Geographic along with Indigenous cartographers, have created a giant floor map, and an accompanying Indigenous Peoples Atlas of Canada, with the names and places as the First People’s knew them.

Rosanna Deerchild is host of the CBC Radio program, “Unreserved”.

“Maps have long been called a tool of colonialization. They’ve carved out pieces of what was indigenous land and replaced them with neat lines of provinces and territories. Colonial names have been written over Indigenous place-names, Rosanna Deerchild said, as she introduced the subject. “Maps are power,” she said.

Charlene Bearhead is an education adviser for the map and the new Indigenous Peoples Atlas of Canada.

Listen“We hear so much about truth and reconciliation and what does it mean in reconciling our understanding and knowledge,” Bearhead told Deerchild during an interview, on the map.

“We expect people to be able to shift their mindset and to open their minds and to understand … who were the original peoples of these [lands] and what were the original names.”

Bearhead says this map will help Canadians do that.

Without provincial or territorial boundaries, and the names, of cities and towns, the map outlines the varied Indigenous communities across the country, the languages spoken, and the treaties signed with the Crown.

Rosanna Deerchild, sitting to the left of Hudson Bay, finds her community, O-Pipon-Na-Piwin, or South Indian Lake on the map, in what is now known as the province of Manitoba. (CBC/Stephanie Cram)

“People have the misconception that treaties came from Europeans, and we know that Indigenous people long before European contact were sophisticated, and negotiated … how that land would be used,” Bearhead explained.

Now touring with the map, Bearhead has witnessed some different reactions to it.

“For the most part Indigenous people walk on the map and it makes sense and they are like, ‘I know where this is, I know the story of this place for my people,'” she said.

“Non-Indigenous people walk onto the map and have this blank look on their faces,” Bearhead said, as they realize there are no provincial boundaries evident.

Rosanna Deerchild and Charlene Bearhead explore the giant floor map which accompanies the Indigenous Peoples Atlas of Canada. (CBC/Stephanie Cram)

“People that are members of the Michel Band [in Alberta] come to the map and it’s so emotional because the Michel Band has never been shown on a map before,” she said, explaining that the Michel Band dissolved in 1958.

Cree students from Northern Québec were delighted with seeing the map for the first time.

“The kids said, ‘my home’s on here, this is where I live.’ I think it instils some pride and some hope with Indigenous people,” Bearhead said.

“There’s so much to learn in this one little spot, because it’s so different.” she said.

Charlene Bearhead is also the educational coordinator for the national inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls, and she was the Education Lead at the National Centre for Truth and Reconciliation.

(With files from CBC)

For reasons beyond our control, and for an undetermined period of time, our comment section is now closed. However, our social networks remain open to your contributions.