Photo: Radio-Canada

On a quiet afternoon on Dec. 6, 1989, a young man armed with a semi-automatic rifle hidden in a plastic garbage bag walked into the hilltop campus of the Université de Montréal’s engineering school with vengeance in his heart.

After lingering at the registrar’s office of Ecole Polytechnique for about an hour, Marc Lépine (born Gamil Gharbi) entered a second floor classroom.

Lépine ordered male and female students to separate, sending the men to the right and the women to the left.

He then ordered about 50 men to leave.

“I hate feminists!” Lépine shouted as he opened fire at the nine women still in the room, killing six of them and wounding three others.

Lépine then left the classroom, B-311, to continue his carnage in other parts of the building.

By the time he turned the gun on himself, seconds after he killed off his final victim with a hunting knife, Lépine had shot 28 people, killing 14 young women.

The Montreal Massacre, as it is now known, sent shockwaves across Canada and sparked an enduring political debate that reverberates to this day.

On one side of this debate are people like Heidi Rathjen, who was at the Polytechnic that day and has devoted her life to tighter gun control in Canada ever since.

“In our reactions, we knew that many things contributed to this tragedy – things like violence, sexism and so on – but one thing that we could wrap our heads around as engineering students was the fact that he was able to carry out all this violence rapidly and effectively because he had legal access to a firearm. And he shouldn’t have had,” says Rathjen, coordinator of PolySeSouvient, or PolyRemembers, a gun control citizens advocacy group.

On the other side of Canada’s gun debate are people like Dr. Caillin Langmann, an emergency room physician and professor of medicine, who argues that gun control measures championed by Rathjen and other gun control activists have done nothing to reduce gun violence in Canada and may have even taken much needed resources from programs that are known to be much more effective in reducing gun-related carnage.

The long-simmering 30-year-old discussion is again back in the news as the government in the province of Quebec launches a new gun registry for hunting and sporting rifles and shotguns and the federal government in Ottawa continues to push proposed legislation that would further tighten Canada’s gun laws.

A brief history of gun control in Canada

A man is seen reflected in the commemorative plaque during a ceremony marking the 28th anniversary of the Montreal Massacre when a gunman shot 14 women to death and injured 14 other people Wednesday, Dec. 6, 2017 in Montreal. (Paul Chiasson/THE CANADIAN PRESS)

The current debate reaches back a long way.

Almost immediately after the Polytechnique massacre, the Progressive-Conservative government of then prime minister Brian Mulroney introduced tighter gun control legislation.

Bill C-17 banned large-capacity magazines and semiautomatic military-style rifles, introduced new regulations on safe storage of firearms and stricter screening and safety training for prospective firearms buyers.

The bill also tightened up the firearms licencing system, requiring applicants to provide references, complete a safety-training course and pass an examination, and introduced a mandatory 28-day waiting period before new licence holders were allowed to acquire a firearm.

In addition, the application form for the firearms acquisition certificate was expanded to screen applicants’ marital and medical status as well as performing criminal background checks. If the applicant was married or divorced, one of the references was required to be from a spouse or former partner.

But, according to Rathjen, the efforts of gun control activists, who had collected over half-a-million signatures, to pass even tougher legislation ran into strong opposition.

“Another thing we didn’t know about gun control in Canada is we do have a very strong gun lobby,” Rathjen told Radio Canada International in a telephone interview.

“It might not be as visible as the NRA (National Rifle Association) in the United States, but we have many-many different groups – hunters and collectors, and merchants and gun clubs, and so on – that opposed stricter controls, so the minister couldn’t pass gun control legislation after the worst shooting massacre in recent Canadian history.”

That prompted Rathjen and Wendy Cukier, a professor at Ryerson University in Toronto, to set up the Coalition for Gun Control.

Cukier became the president of the organization, which she heads to this day, while Rathjen took a break from her engineering career to become the coalition’s only paid employee.

When the Liberal Party led by Jean Chrétien trounced the Progressive Conservatives in the 1993 federal election, gun control activists won a powerful ally in the federal legislature.

“We worked six years until we – with all kinds of groups, police groups, women’s groups – passed comprehensive gun control in December 1995,” Rathjen says.

“At the time we achieved legislatively everything we asked for.”

Bill C-68 made it a criminal offence to own a firearm without a licence, including a hunting rifle or shotgun. However, the key aspect of the Liberal legislation was the creation of the Long Gun Registry.

All long guns – hunting rifles, shotguns, sports rifles like the once used in biathlon – now had to be registered (handguns in Canada had to be registered since 1934).

With her mission accomplished, Rathjen left the coalition to once again focus on her career.

Long gun registry fight

Poly Remembers co-ordinator Heidi Rathjen speaks during a news conference calling on the government for increased gun control in Ottawa, Thursday, Nov. 30, 2017. Quebec’s attempt to establish a provincial firearms registry is facing resistance. Less than 20 per cent of the long guns believed to be in circulation have been declared. (Adrian Wyld/THE CANADIAN PRESS)

Things went well for a while, except for the fact that federal Long Gun Registry was way over budget for various reasons, Rathjen says.

In fact, the Long Gun Registry had surpassed its initial budget estimate by more than $1 billion, sparking outrage and adding much-needed ammunition to the opponents of the registry.

The political winds in Ottawa started to change.

Wounded by a damaging patronage scandal and internal squabbling, the Liberals lost power to the Conservatives in 2006,

The Conservatives were born in 2003 out of a shotgun marriage between the remnants of the Progressive Conservative Party and the ascendant Canadian Alliance, a populist right-of-centre party with strong roots in Western and rural Canada, where the long gun registry was despised.

The minority Conservative government under the leadership of then prime minister Stephen Harper attempted to dismantle the Long Gun Registry in 2010, but a private member’s bill was defeated in the House of Commons.

In 2012, after having secured a parliamentary majority a year earlier, the Conservatives finally kept their electoral promise to kill the federal gun registry.

“So we did good five steps forward and four steps backwards,” Rathjen says.

Quebec opts for its own solution

Quebec Interim Public Security Minister Pierre Moreau speaks at a news conference after he tabled a legislation creating a gun registry, Thursday, Dec. 3, 2015 at the legislature in Quebec City. Moreau, centre, is accompanied by Polytechnique victim Helene Thibault, from the left, Quebec Solidaire MNA Manon Masse, Polytechnique victim Nathalie Provost, Opposition MNA Stephane Bergeron, Polytechnique victim Heidi Rathjen, and CAQ MNA Andre Spenard. (Jacques Boissinot/THE CANADIAN PRESS)

But in Quebec, scarred by the memory of the Polytechnique massacre, the 2006 mass shooting at Montreal’s Dawson College, and the 2012 election night attempt on the life of sovereignist premier-elect Pauline Marois at the Metropolis nightclub in Montreal – all committed with legally obtained firearms – the idea of abolishing the registry was not politically palatable.

The province fought hard, going all the way to the Supreme Court of Canada, to preserve the Quebec portion of the registry.

However, on March 27, 2015, Canada’s highest court dismissed Quebec’s appeal challenging the constitutionality of destruction of long gun registry records, and refused to order the transfer of these records to the province.

On June 9, 2016, with cross-party support, Quebec’s National Assembly overwhelmingly passed legislation (99 for, 8 against, 0 abstentions) that created a provincial long gun registry.

But the law, which came into effect on Jan. 29, 2019, has run into fierce opposition from many Quebec gun owners and Indigenous groups, who argue it unfairly targets law-abiding gun owners for crimes committed by “a couple of lunatics.”

Quebec Indigenous and Inuit groups say the law interferes with their traditional lifestyle, which depends to large degree on sharing resources and equipment for hunting and fishing, including firearms. They also argue the provincial legislation runs counter to land claim and self-government agreements signed by the province with Quebec’s Inuit and Cree communities.

They also point to technical difficulties of online registration of firearms in remote communities without access to high speed Internet and filling out forms that are available only in French and English.

As of Feb. 4, only 397,898 non-restricted firearms were registered in Quebec, compared to 1.6 million guns that were registered in the province in 2012 just before the federal gun registry was terminated.

Guy Lavergne, a Quebec-based attorney who represents the National Firearms Association, one of the most vocal gun owner associations in Canada, says, based on his experience, even the 1.6 million figure in the old federal registry was not complete.

There was a large number of non-restricted firearms that were not registered in the federal registry because of resistance to the registration system, he adds.

Lavergne estimates there are about two million long guns in Quebec, which means only about of one-fifth of long guns in the province have been registered so far.

As an avid sports shooter and hunter, Lavergne says he understands the concerns of ordinary gun owners who feel ostracized and marginalized by the prevailing anti-gun political discourse in Quebec and Canada.

Legal and political arguments against Quebec gun registry

There is a revolt brewing in small towns across Quebec against a new law forcing long-gun owners to register their non-restricted firearms with the government. Hunting rifles are seen on display in a glass case at a gun and rifle store in downtown Vancouver, Wednesday, Sept. 15, 2010. (Jonathan Hayward/THE CANADIAN PRESS)

Lavergne says the NFA’s opposition to the Quebec gun registry has both a legal and a political perspective.

“The legal aspect is that in the current state of the law the government of Quebec has no business creating a provincial gun registry because that falls within the federal constitutional powers and that’s what the Supreme Court of Canada decided in 2000 when a similar gun registry was created by the federal parliament through the Firearms Act,” he says.

Lavergne says the NFA filed a constitutional challenge to the provincial legislation in 2016.

The case is currently before the Quebec Court of Appeal and will be heard on Feb. 26.

The NFA lost in the lower courts, which accepted the Quebec government’s argument that the legislation is within provincial jurisdiction.

The NFA argues that the legislation does not deal with the property aspect of the firearms and it’s not about the administration of justice, which puts it outside provincial jurisdiction.

But, Lavergne says, there is also a political and ideological aspect to the NFA’s opposition to certain gun control measures advocated by the province and the Liberal government in Ottawa.

“I think the main problem is that gun control in general instead of addressing the criminal use of firearms, makes criminals out of honest people,” he says.

“The gun registry – whether it was the old one or the current provincial long gun registry – only targets law-abiding gun owners, it only targets people who are licenced to own firearms and it doesn’t address the criminal use of firearms whatsoever.”

The legislation creates a series of infractions where no harm has occurred, he adds.

Lavergne says gun control is a political response to what happened at Ecole Polytechnique and other high profile mass shooting incidents.

“It is a way for the government to basically hold all gun owners, a whole class of people, responsible for the actions of a couple of lunatics.

“I think that is the main reason that gun owners are so vehemently opposed to the Quebec gun registry.”

Lavergne says gun owners feel that they’ve already been checked by police and by government authorities through the licencing process and yet they are viewed as would-be criminals with their every action, movement and purchase being monitored by police.

‘A fact of life’

Guy Morin, vice-president of a Quebec group opposed to the provincial long-gun registry, is shown at his home, Thursday, Feb. 25, 2016 in Quebec City. (Jacques Boissinot/THE CANADIAN PRESS)

Not surprisingly, Rathjen sees the matter differently.

“It was very predictable that the gun lobby would organize campaigns and boycotts and petitions. Their boycott was very effective” she says.

The boycott was aimed at putting so much pressure on the provincial government that it would back down on the day that the law would come fully into effect on Jan. 29.

“Happily the government held firm, said that it would not back down in front of the pressures of the minority of gun owners that are against the law, and that fines will apply,” says Rathjen.

Gun control advocates are confident that most gun owners, even if they oppose registration, are law-abiding citizens and will eventually comply, especially since most of them are not willing to pay $500 to $5,000 in fines if they don’t comply, she adds.

“Registration was a fact of life for 12 years while the federal long gun registry was in effect, hunting and target shooting continued, it wasn’t the end of the world, businesses continued, sports continued,” she says. “So the only objection now is in principle, it’s ideological.”

Rathjen says the legislation enjoys wide-ranging support of every political party in the National Assembly, she said.

“It was passed fair and square after eight years of judicial procedures, legislative procedures, regulatory procedures,” says Rathjen. “Every step of the democratic process was respected in adopting this law.”

To give in to the demands of a vocal minority of gun owners would be absurd, she argues.

“It would be like saying the majority of smokers are against banning smoking in the workplace and so they’re going to decide not to respect the law.

“The registry bill was passed not to please the gun owners, it was passed as a public safety measure.”

She says it is now up to the provincial government to come up with strategies to ensure higher compliance with the law.

“The government could be aggressive with fines or it could be softer with a combination of fines and more education and reach-out, but either way the law is staying and eventually it will be respected, we’re confident.”

Rathjen rejects the idea that the legislation unfairly targets law-abiding gun owners.

“The authors of all the mass shootings that we’ve seen in Canada over the past few years have been legal gun owners, [these mass shootings were] committed with legal guns that the system allowed these people to have and they shouldn’t have had,” Rathjen says.

Registration is just one component of gun control, a tool that helps police to remove guns from people who shouldn’t have them, she argued.

“At some point the system did not work in terms of alerting the police of authors of these tragedies, that they had mental health issues for example, all of them did,” Rathjen says..

“These tragedies could’ve been averted if the different components of gun control worked together properly, if people would have alerted the police about the mosque shooter’s mental health problems, then the police might have determined there was a risk and decided to remove the guns from this individual.”

Useful tool for law enforcement?

Montreal police officers look at a weapon seized from a house in Montreal, Wednesday, July 31, 2013, following a standoff with an armed man. (Graham Hughes/THE CANADIAN PRESS)

Clément Robitaille, head of prevention and fight against criminality at the Quebec Ministry of Public Security, and the man responsible for managing the newly created provincial firearms registry, says it creates a database that is very useful for police work.

“It allows us to answer three very important questions: who has firearms? What kind of firearms? And where are they being stored?”

Robitaille says there are several situations where this information could be of great use for law enforcement, including when the permit holder presents a danger to himself or others.

“This kind of information at the fingertips of police officers could help prevent family dramas and make life safer for all Quebecers,” he says.

Lavergne, the NFA lawyer, dismisses the arguments by police that they need the registry to be able to trace guns and solve crimes as bunch of baloney.

“The police have been asked, ‘How many crimes have you been able to elucidate through the long gun registry?’” he says. “And the answer was, ‘We don’t have the statistics or data on that.’”

Even in the cases such as the Polytechnique massacre, the Metropolis and the Quebec mosque shooting – all of which were carried out with legally purchased guns – having a registry would have played no role in preventing these tragedies or even solving these crimes.”

Metropolis shooter Richard Bain was caught on the scene and Quebec mosque shooter Alexandre Bissonnette called the police and turned himself in, Lavergne says.

Lavergne notes that both men had mental health problems and Bissonnette admitted to lying on his firearms licence application form about his mental health history,

While proponents of stricter gun control point to these facts as further proof for the need for much tougher and more in-depth background checks, Lavergne says the resources spent on keeping another layer of bureaucracy would be better spent on funding mental health initiatives.

Rathjen differs, saying one can’t measure whether a law is effective or not by looking at anecdotes or individual incidents, because when something is prevented, there is no trace of it.

“Because we have much tougher gun control than in the United States, we have much less gun-related crime, gun-related murders, but you still can’t name the people that were saved by having tougher gun control, in the same way that you can’t name the people that were saved for having speed limits on highways,” she says.

“We still have accidents but it doesn’t mean that the speed limits are no good and we should get rid of them. It just means we could do better.”

Gun control measures work on the populational level, Rathjen argues.

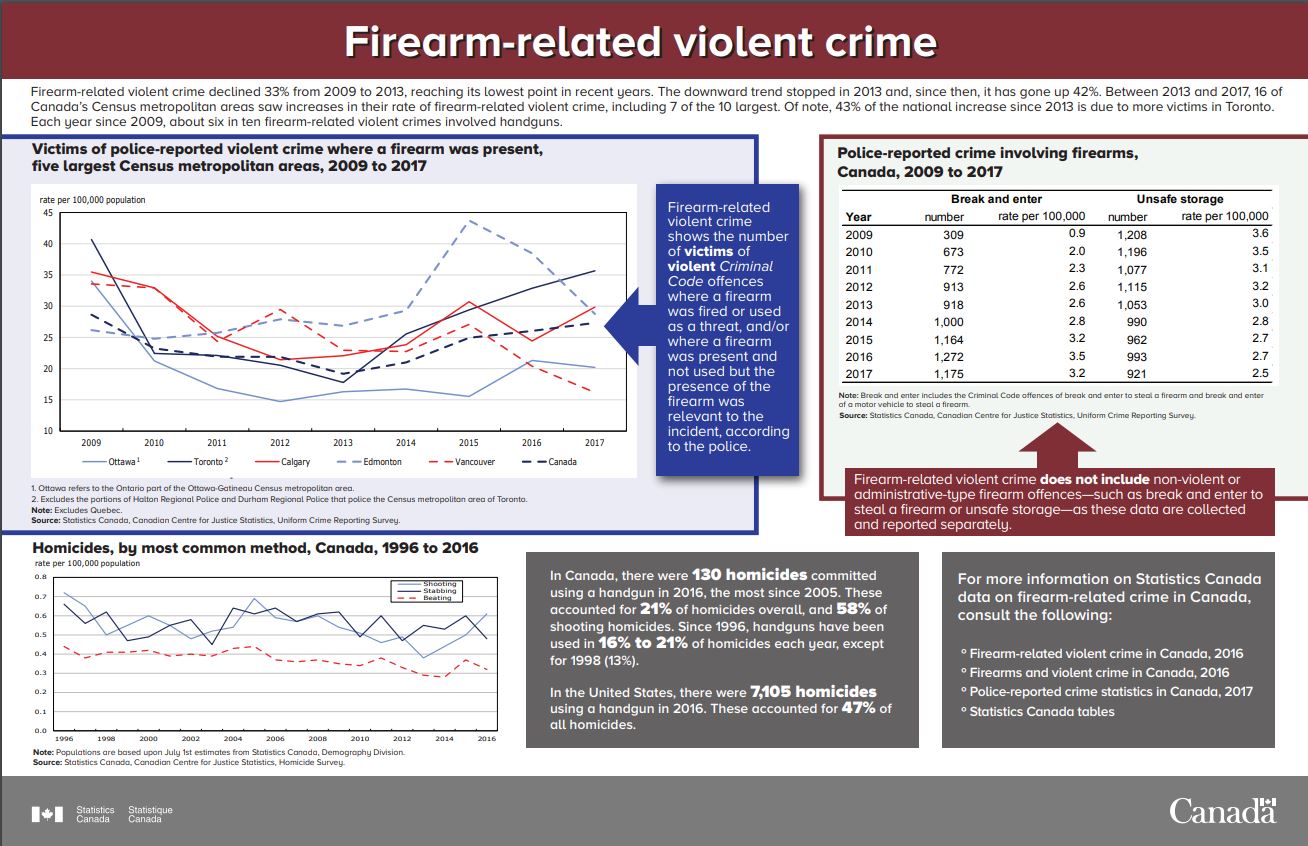

“We have seen with the federal law, which was in effect from about 2000 to 2012, that during that time there was constant reduction in gun-related homicides to a point when in the last years of the registry, the rates of gun homicides were at the lowest ever recorded in 40 years.”

“And since the federal gun registry was abolished, all we’ve seen is year after year, four years in a row of increase in gun-related homicides to a point now that the rate is at its highest point in 25 years.”

What’s behind the numbers?

(Source: Statistics Canada)

But for Dr. Langmann, the emergency room physician and professor, the statistics often cited by gun control advocates tell a completely different story.

He has published peer-reviewed statistical analysis of Canada’s gun related homicides in scientific journals and has been called to testify in front of a parliamentary committee looking into federal gun control legislation.

Langmann’s research has found “no significant beneficial association” between various gun control laws introduced since the late 1970s and gun-related homicide rates in Canada over the last 40 years.

“It’s actually not an unusual finding at all,” Langmann said in a phone interview with RCI from Hamilton, Ontario, where he is based.

“There is a number of studies that have demonstrated that most of these laws had no effect on homicides.”

Langmann says the problem with gun control as a tool for preventing gun related violence and suicides is that substitutes for legal guns are easily available.

He adds that someone who intends to commit a crime using a gun can relatively easily obtain an illegal firearm on the black market and most spousal homicides are committed through beatings, stabbing or strangulation.

And, he says, someone intent on committing suicide can turn to hanging instead, which is as deadly as a firearm.

“If you look at actual legal gun owners, very few of them commit homicide a year,” Langmann says. “We know that there are at least two million licenced gun owners in Canada and there is maybe 10 – and it fluctuates wildly – sometimes 17, sometimes much less than 10 homicides a year by those people. So registering a firearm is not going to affect that.”

He says what can change Canada’s gun related crime statistics are measures aimed at affecting the demand side of the equation.

“It’s becoming more clear that quite a large number of homicides in Canada are due to gang violence or crime-associated violence,” Langmann says.

The factors that drive this kind of gun violence are related to protection and self-defence, revenge, theft, a vacuum in hierarchy such as imprisonment or loss of leadership, and the age of the participants, as well as social cohesion of the community, Langmann says.

And most of these homicides are committed by younger men, who are most at risk of both becoming a victim or perpetrator of homicides, he says.

“What we’ve found through studies is that if we try to divert those youth at risk, to capture them committing petty crime before they get involved in significant criminality, or we discover children, who are at risk due to poverty, family and home factors, and we divert them away from belonging to gangs into better education and diversion away from violence, cognitive behavioural therapy, which involves understanding their emotions and behaviour, modifying behaviour, we can actually significantly reduce homicide rates and we can reduce rates of membership in gangs,” Langmann says.

“Those are hard things to do, they require more long-term approach, they’re not politically exciting and therefore most politicians just aren’t interested.”

Firearms Bulletin 2016 by Statistics Canada on Scribd

Langmann says mass shootings such as the Polytechnique massacre or the more recent Quebec mosque shooting are a statistical anomaly and are exceedingly rare.

While for obvious reasons they galvanize public attention, he says they are very hard to prevent.

Langmann adds that there are other substitutes to guns, as shown by last April’s van attack in Toronto, which killed 10 people and injured 16.

“I think what you’re looking at is trying to stop something like a shark attack,” he says.

“They are extremely rare and we don’t really understand all that is involved in contributing to this.”

Banning firearms is not a solution in a country like Canada where a lot of people are involved in hunting, he adds.

“And hunting rifles are probably the most dangerous of all firearms in terms of a trauma from the medical perspective,” Langmann says.

“They can cause significant amount of damage, their cartridges are large and high-powered.”

In a brief submitted to Parliament’s Standing Committee on Public Safety and National Security in April of 2018, Langmann even suggested doing away with Canada’s current system of firearms classification.

“What is becoming clear from current research is that the type of firearm, and control of certain types of firearms or magazine size restrictions results in no reduction in firearm homicide or suicide,” Langmann wrote.

“Extensive analysis of mass homicide events demonstrates that mass killers can use a wide variety of firearm types, even firearms with small magazine capacities, to cause a significant number of deaths. There does not appear to be an association with magazine capacity and death as the shooter often appears to have enough time between shots to reload.”

Statements like this are an anathema for gun control advocates in Canada.

“No matter what you call them, when a weapon allows you to kill dozens and dozens of people in a matter of minutes, because you have rapid fire accessories, like large capacity magazines or you have these killer bullets that explode on contact, or sniper rifles that could shoot at up to two kilometres, these are weapons that are much too risky, their risk for public safety far outweighs any benefit that you can get from hobbies or sports purposes,” Rathjen says.

“These are the weapons designed to kill in military contexts that should be banned. So I don’t care what you call them but these weapons shouldn’t be allowed in the hands of civilians.”

Gun control activist Heidi Rathjen speaks during a news conference in Montreal, Friday, Nov. 28, 2014. (Graham Hughes/THE CANADIAN PRESS)

But it is precisely this kind of language that gets gun owners riled up.

They point out that exploding projectiles are illegal for sale to civilians not only in Canada but in most countries around the world and are reserved for military use, and even then usually against material targets such as enemy vehicles and aircraft.

Some hunting bullets – hollow point and soft-point bullets – are designed to mushroom or expand upon impact to cause maximum damage in the prey to incapacitate it and ensure its quick death but such bullets were banned from the military use in international conflicts by the 1899 Hague Convention.

In fact, many military-grade bullets cannot be used for hunting because they are designed to penetrate their target through body armour or other obstacles and do not provide enough stopping power for large game.

Large capacity magazines have been illegal in Canada since 1990 as the result of legislation that followed the Polytechnique massacre. To be legally sold in Canada, all semi-automatic rifle and shotgun magazines are limited to five rounds. Modifying magazines to increase their capacity is also a crime in Canada.

“If somebody is willing to commit a crime in order to commit another crime, I don’t think that’s a gun problem, I think it’s a criminality problem,” says the NFA’s Lavergne.

Nevertheless, says Rathjen, that didn’t stop the Quebec mosque shooter Alexandre Bissonnette and the Metropolis shooter Richard Henry Bain from tampering with the magazines of their Czech-produced semi-automatic rifles to remove the pins that limited them to accepting only five rounds and to increase their capacity to up to 30 rounds.

Fortunately, in both cases the rifles jammed, preventing both Bain and Bissonnette from unleashing their full fire power.

“Just the fact that these weapons are out there and they are able to accept large capacity magazines, and these large capacity magazines are easily modifiable to the full capacity, to us that’s the risk,” Rathjen says.

“We’ve had many instances of these shooters tinkering with their magazines that are legal in order them to allow to contain all the bullets that they are designed for originally.”

And as far as sniper rifles that can shoot up to two kilometres, Lavergne says that’s another example of gun control activists using scare tactics on a population that knows little or nothing about firearms.

He points out that such sniper rifles are very expensive, costing up to several thousand dollars not counting the cost of optical sights, which could easily double the price of the weapon. These rifles weigh anywhere from 12kg to 18kg (a typical hunting rifle or a semi-automatic carbine weighs between 3kg and 4kg).

It takes tremendous skill to operate such rifles and even the Canadian military, which is internationally renown for its snipers, has only a few dozen people at most who can engage targets at distances beyond 2,000 metres.

New federal legislation in the works

Recreational shooter Pat Eyre fires a round from her 9mm Glock handgun at the United Shooting Range in Gormley, Ont., north of Toronto, Friday, Jan. 3, 2003. (Kevin FrayerCP PHOTO)

The Liberal government is currently poised to pass new federal firearms legislation that Ottawa says is necessary to reduce the frequency of violent gun crime.

In the last election, the Liberal Party ran on the promise of reversing a decade’s worth of Conservative changes to gun rules that were introduced by the previous Liberal government.

Liberals argue that Bill C-71, introduced by Public Safety Minister Ralph Goodale, fulfils that commitment through an overhaul of the background check system, new record-keeping requirements for retailers and further restrictions on transporting restricted firearms.

“The provisions in Bill C-71 are modest and reasonable, and they do not entail a significant new cost,” Goodale said in introducing the bill.

“Bill C-71 an important piece of legislation in support of public safety and the ability of law enforcement to investigate gun crimes, while at the same time being reasonable and respectful toward law-abiding firearms owners and businesses.”

Rathjen says even though her group is disappointed with Bill C-71, it supports the legislation, which is currently moving through the Senate, because it’s “a step forward.”

“It brings in some measures that are absolutely critical, for example, the obligation to make sure that the person you’re selling your gun to has a valid possession permit, which is not the case now,” Rathjen said.

“But to us it’s a very disappointing piece of legislation because it’s so weak compared to what the Liberals could have done within the scope of their election promises.”

Rathjen has sharp words for the Liberal government of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau, saying it is “terrified of the gun lobby” and doing too little too late with legislation on gun control.

“It’s very disingenuous that they’re looking into it at a time when it’s probably too late to get anything done concretely, which is terrible because the Liberal Party actually ran on getting handguns and assault weapons off our streets, and yet there is nothing about that in the bill they did table, which still hasn’t been passed,” she says.

“And if they say they are going to anything about it, they won’t have time.”

The Liberal bill brings back the legislative requirement for keeping commercial sales records of all gun purchases, which was eliminated by the Conservative government in 2012.

“The problem is they [the Liberals] are bringing it back in a way that makes it extremely difficult for authorities to access this data,” Rathjen says.

“Police need a search warrant in order to trace one gun… there is no way to pool the data, there is no way for authorities to do quality checks to see if the law is being applied.”

Lavergne, meanwhile, says for gun owners the proposed federal legislation raises many of the same objections as the provincial gun registry in Quebec.

“Again it is targeting law-abiding gun owners,” he says

“It is creating additional bureaucracy where none is required and it doesn’t do anything to address the real problems of gun violence.”

One of the gun owners’ biggest objections to the proposed legislation has to do with something called Authorisation to Transport (ATT).

There are three classes of firearms in Canada: non-restricted firearms (shotguns, hunting and sporting rifles); restricted firearms (which includes handguns, some more compact semi-automatic rifles such as the AR-15) and prohibited firearms (fully automatic guns and assault rifles, sawed-off shotguns and rifles, and smaller handguns that are easier to conceal).

Under the current rules, restricted firearms can only be legally possessed at authorised locations such as the owner’s residence or a certified shooting range.

In addition, all restricted firearms owners require an ATT from a provincial or territorial Chief Firearms Officer (CFO) in order to transport a restricted firearm from one authorised location to another.

“For example, I’m a member of a gun club in Ontario and I have an authorization to transport handguns between my house and that gun club,” Lavergne says. “I’m not allowed to make a detour, I’m not allowed to stop along the way and I have to take the most reasonably direct route, and while I do so, I have to transport these handguns under lock, in a locked case in the trunk of my car.”

Under legislation that was passed by the Conservative government in the last months of their tenure, this process of authorizations had been simplified, Lavergne says.

Instead of seeking a separate authorization every time a gun owner wanted to go to a shooting club or a gunsmith, an ATT was issued for a number of pre-approved locations.

“Those would be, for example, to take your firearm to a gun show or to an appraiser, or to a gunsmith for a repair, or to any shooting range in the province,” Lavergne says

“Basically instead of filling out an application, faxing it to the Chief Firearms Officer and getting a piece of paper in return every time you wanted to go to one of these places with a handgun, you had one that was issued to you at large but only for those locations. It doesn’t allow you to take your handgun to the mall or to a wedding.”

The new Bill C-71 reinstates the requirement for separate ATTs for all authorised locations except for gun ranges. In other words, if Bill C-71 becomes law, a gun owner is only authorised to transport his restricted firearms between his residence and his gun club.

Lavergne says that if the firearm malfunctions or needs some repairs, the gun owner cannot simply drive from the gun range to see his authorised gunsmith, but has to return home file a separate ATT, wait for it to arrive to be able to legally transport it for repairs.

Another aspect of Bill C-71 that is vehemently opposed to by many gun owners has to do with rules governing the purchase or transfer non-restricted firearms – hunting rifles and shotguns – between two licence holders.

Under the current legislation, a gun owner who wants to sell or transfer his or her firearm to another person has to check whether the buyer has a valid firearm Possession and Acquisition Licence (selling or transferring a firearm to someone who doesn’t have a licence is illegal).

Under the proposed legislation, the seller would not only have to see the licence but also call it into the Canada Firearms Centre (CFC) operated by the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP) and verify whether the licence is a valid one.

The seller then has to obtain a reference number to show that the transaction has been authorised by the CFC.

“Basically, the firearms licence is no longer a valid document to purchase firearms because every transaction has to be vetted by the RCMP,” Lavergne said. “Again it’s adding a layer of bureaucracy and it creates a crime when no harm occurred.”

Lavergne says that because the government keeps a record of each transaction, Bill C-71 in effect recreates the federal long gun registry.

“The Trudeau government is saying, ‘We’re not reinstating the long gun registry,’ but the reality is they’re recreating the process and they’re keeping the records of transaction, so in essence once every single long gun would have changed hands one time, you will have a long gun registry,” says Lavergne.

Keeping guns out of the hands of criminals

A plain clothes officer carries a firearm to display on a table which contains guns, drugs, and money as Ontario Provincial Police host a news conference in Vaughan, Ont., on Thursday, Feb. 23, 2017, detailing an investigation into illegal firearms and trafficking of illegal drugs in Ontario, Quebec and the United States. (Chris Young/THE CANADIAN PRESS)

When asked whether there are gun control measures he would support, Lavergne says that measures that make sense to him are the ones that target criminal activity and prevent people with criminal intent or criminal behaviour from having access to firearms.

The NFA would have no problem with legislation that prevents people who have been convicted of violent crime or have exhibited violent behaviour from purchasing or possessing firearms, he adds.

“But by and large the problem with gun control as it has been applied in Canada is that most of the resources are put to target non-criminal behaviour and just creating layer upon layer of bureaucracy,” Lavergne says.

“That’s not a good use of resources but it allows politicians to say, ‘We’ve addressed the problem,’ but no, they’re not addressing the problem.”

‘It’s not my thing but it was fun’

Despite her advocacy for stricter gun control, Rathjen says she doesn’t hate guns as is often claimed by her opponents.

“Wendy and I, when we worked early on to get the laws passed in the 1990s we met with friendly gun owners, we went to shooting ranges and shot,” Rathjen says. “I don’t know, maybe I enjoyed it a bit, it’s not my thing but it was fun. I could see how people can enjoy it.”

But that’s not the point, she argues.

“I like driving my car, it doesn’t mean I’m against licencing and registration,” Rathjen says.

“You can enjoy guns but you can also recognize that these are dangerous objects when they fall into the wrong hands and it’s to everyone’s benefit to make sure they’re strictly controlled.”