Freedom, Liberté, Liberdade. Diogo Ramos now sings these words in three languages – English, French and Portuguese – as he released officially this month the videoclip for the single Liberté je t’aime (Freedom, I love you) during a impromptu show given in one of Montreal’s lively backstreets. The song is part of an album released in 2018, Samba sans frontières (Samba without borders). The Brazilian singer-songwriter and guitar player had been holding on to the videoclip and expected to launch it in March this year, but the COVID-19 pandemic prevented the official launch.

The main collaboration of the whole album is certainly with fellow Brazilian singer Bia, who is well-known in Quebec, but also in Europe. She adapted the classic samba Liberté je t’aime, that Diogo Ramos had already recorded 20 years before in Brazil. The lyrics were in Portuguese, but he wanted the song to be heard in French. Bia is an expert in this kind of writing, since she herself recorded a whole album of adaptations of French and Brazilian songs, Coeur vagabond.

Bia Krieger sings with Diogo Ramos during an impromptu show in a Montreal backyard on June 17, 2020. (Photo Credits: Joana do Valle)

The video for Liberté je t’aime was recorded last summer on a rooftop in the trendy Plateau Mont-Royal neighbourhood, with Bia and Diogo Ramos’ full band, with some of the best Brazilian musicians in Quebec: Lissiene Neiva on back vocals, Rodrigo Simões on cavaquinho, Gabriel Schwartz on the flute, Olivier Hebert on the trombone, André Galamba on the bass, and Sacha Daoud on the drums.

“It was the most beautiful day in my life, after the birth of my two daughters,” he recalls.

The video shows performers of samba de gafieira, an elaborate and elegant kind of samba dancing that reminds of tango. The dancers in the video are part of the Sambakana collective, which organizes an international gafieira festival every year in Montreal.

The dancers were invited to take part in the mini-show organized by Diogo Ramos in mid-July in a Montreal backyard. That felt as good as spring coming back after a very long and harsh winter.

Dancers perform samba de gafieira during a mini-show in a backstreet of Montreal on July, 17, 2020. Brazilian singer Bia Krieger sings along with Diogo Ramos to celebrate the official launch of the videoclip for his single “Liberté je t’aime”. (Photo Credits : Joanna do Valle)

From Bahia to São Paulo

A decade ago, Brazilian-born Diogo Ramos came to Montreal, Quebec, in search for a better life, much like his parents when they left their native Bahia, in Northeastern Brazil, to settle in São Paulo, the country’s metropolis.

Ramos was raised in the big city, but never forgot his Bahian roots, in particular thanks to the music played by his uncles. Learning the guitar at age 13, he won his first award three years later with an original composition, and then never stopped playing and composing. In Brazil, he collaborated with other artists, such as world-famous singer-songwriter Chico César.

Following the example of the Tropicália movement founded in the late 1960s by young Northeastern artists such as Gilberto Gil and Caetano Veloso opposed to the military regime, Diogo Ramos’ involvement with music is one of a citizen defending democracy. First in Brazil, and now in Canada, he pleads for freedom and defense of civil rights, and the current situation in his homeland is a cause for “despair”, he says.

“Brazil’s identity has nothing to do with President Jair Bolsonaro. Actually, I think that his refusal to acknowledge the severity of the COVID crisis – that he merely considered as “as small flu” – is causing one of the largest genocides of our history,” Diogo Ramos said emphatically during a telephone interview this month.

“He said he tested positive to the coronavirus, then negative, but we never know whether he is spreading fake news because he refused to disclose the results of his tests, and this is dividing the population,” Diogo Ramos commented.

Brazil’s national health workers union accused Bolsonaro of crimes against humanity at The Hague’s International Criminal Court (ICC) for his “negligent and irresponsible actions” in dealing with the pandemic, which caused over 90,000 deaths to date. This amounts to a “genocide” in the eyes of the Brazilian health professionals. And although the pandemic in Latin America’s largest country is not showing any signs of receding soon, Mr. Bolsonaro’s government ordered this Wednesday the reopening of Brazil’s borders to international flights.

The mere decision to move to Quebec was also a political one : “Europe is too crowded, and I discovered thanks to the Bureau du Quebec in São Paulo that this small part of North America is a bit more socialist,” recalls Diogo Ramos. “I did the right thing,” judges Ramos in retrospect, 10 years after he moved to Québec. “I feel very proud of my decision.”

Soon after his arrival, Diogo Ramos started collaborating with other Brazilian artists established in Montreal. The pioneer Paulo Ramos – who is not a relative, despite bearing the same name – brought his samba to Quebec in the late 1980s, and Rommel Ribeiro, whose sensibility immediately “clicked” with Diogo’s. The two joined forces, and Diogo produced Rommel’s excellent first album, Egológico Recycle.

Watch below “Nhiazinha”, one of the tracks of Rommel Ribeiro’s album produced by Diogo Ramos, in a recording at the Montreal Museum of Fine Arts.

To this day Diogo Ramos is grateful to his French teachers at Cegep du Vieux-Montreal who introduced him to the specificity of Quebec’s “société distincte” (“different society”), a status it enjoys within the Canadian Confederation after René Lévesque led his “Révolution tranquille” (Quiet Revolution) in the 1960’s.

After collaborating with local artists, learning French and studying the guitar at Université du Québec à Montréal (UQAM), Diogo Ramos felt he started to feel like a “Québécois”, and felt ready to express his gratitude in French. Which is also a way of translating his mixed identity into music : “This country has welcomed me and respected me. I wanted to give some love in return,” he said.

Thanks to the free “Francization” program offered by Québec’s government, Ramos had discovered the national troubadours at the core of the province’s specific popular culture. It is their words he decided to sing with his own “Brazilian sauce” in his first Canadian album released in 2018, Samba sans frontières – Samba without borders.

A grant by the Conseil des Arts et des Lettres du Québec allowed him to study in greater depth the work of traditional “chansonniers”, leading to a personal album with eight tracks in French out of ten – being that one is in Portuguese and one is instrumental.

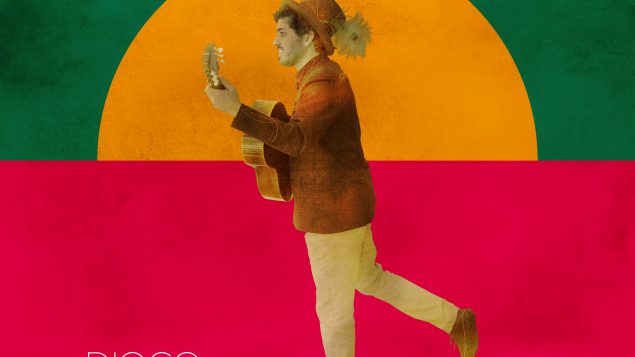

Diogo Ramos released “Samba sans frontières” in 2018 and performed a tour in Brazil, Europe and North America in 2019. (Photo Credits: Lidia Barreiros)

Samba sans frontières, Diogo Ramos tells me, is a hymn to Quebec’s society, rooted in the research he performed on three poets who are part of the social fabric of the French Canadian province. Diogo Ramos mentions in particular the iconic poet Gilles Vigneault, with whom he identified, maybe because of his political commitment during the Quiet Revolution and in favour of self-determination for Quebecers.

“In the song On ne sait jamais, Vigneault’s words express precisely what I am feeling”, says Ramos, and singing the lyrics in French over the phone: “Il ne faut pas fermer son coeur à l’étranger, au voyageur”.

“One shall not close their heart to the stranger, to the traveler.”

“Immigrants from the world over are meeting with Québec’s culture, and if people can open up to them, we can all shine together! It is like feminism. We made some progress, but we have to continue pushing for more; we have to keep learning.”

This need for dialogue is even more acute in these times of pandemic, he says, citing the Black Lives Matter (BLM) movement that denounces systemic racism, and again citing the great Gilles Vigneault who, in a recent interview with a Quebec newspaper, said that we are all responsible for ourselves, but also for our neighbours, and that we should ask ourselves whether we are worthy of this planet, and whether we should go on as usual.

Diogo Ramos feels proud that half a million people gathered in Montreal for the Climate march led by Swedish activist Greta Thunberg. Among the new generations, he admires a young lawyer and social activist of Haitian descent, Fabrice Vil, who inspires him in his fight against racism and for a dialogue between cultures. All of these elements resonate with his work as a musician, he says.

“I want to make music to change the world. We should make more music and less cars,” he says, reminding me of an old graffiti that was painted on Paris walls in May 1968: Make love, not war…

Singing toads

Another famous “chansonnier” who inspired Diogo Ramos is Félix Leclerc – the first Quebecer to enjoy success in French cabarets in the 1950s. He adapted the song Hymne au printemps (Ode to Spring), which celebrates the beauty of Nature: “Près du ruisseau sont alignées les fées/Et les crapauds chantent la liberté”, which would translate into: “Near the stream are aligned fairies/And the toads are singing freedom.”

The same connexion with nature and simple pleasures is felt in Orange, a song with lyrics by the filmmaker Pierre Perrault, mostly known for his documentary films documenting life in rural Quebec, but less known as a poet.

Friendhsip is definitely key in Diogo Ramos artistic collaborations, and if many of his poet friends from Quebec already passed, he had the honour to meet Gilles Vigneault and to sing On ne sait jamais to him last summer. “He was touched, and so was I,” he remembers.

His close friendship with Bia, made of music and dance won’t certainly fade away, and he still remembers the day he overcame his shyness to call her and ask whether she could write French lyrics for a music he’d made.

“She was so generous and accessible, he says. She asked me my address, and immediately cycled to my house.”

Less than an hour later, the French lyrics for Voyageur were on the paper. “I didn’t touch a thing. It was perfect.”

For reasons beyond our control, and for an undetermined period of time, our comment section is now closed. However, our social networks remain open to your contributions.