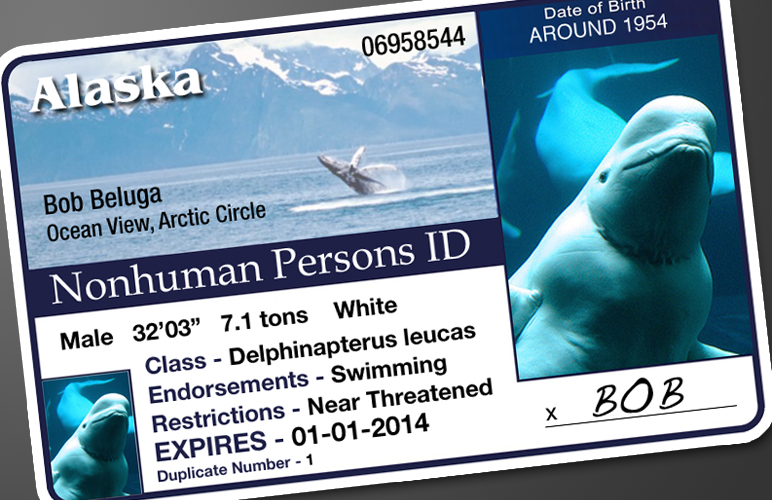

Are beluga, bowhead whales ‘nonhuman persons’ who shouldn’t be hunted?

Are dolphins, porpoises and whales so intelligent and self-aware that they should be treated as “nonhuman persons” — entitled to individual rights, including freedom from being hunted by people?

Are dolphins, porpoises and whales so intelligent and self-aware that they should be treated as “nonhuman persons” — entitled to individual rights, including freedom from being hunted by people?

The answer — according to a recent symposium at a national science conference that included philosopher Thomas White and dolphin biologist Lori Marino — may challenge Alaskans’ long-held assumptions about the ethics of harvesting certain species of marine mammals.

Most Alaskans believe that it’s OK to kill for food in sustainable harvests conducted with minimal waste and humane dispatch. Traditional Alaska Native culture also teaches that these harvested animals should be revered, with any successful hunt considered a blessing.

But what if the animals in question can look in a mirror and recognize themselves as individuals — a recent finding about dolphins?

What if they’re “people,” just not of the Homo sapiens variety?

If Alaska species such as beluga and bowhead whales actually share the capacity for self-recognition, culture and intellect now documented in dolphins, they would therefore deserve the “moral standing” due to “persons,” White explained in an email to Alaska Dispatch.

“No individual ‘person’ — no matter the species — can, from an ethical perspective, be treated as an object or piece of property for someone else’s use,” White added. “If humans make that claim about ‘human persons,’ I don’t see any way that we can say anything different about a ‘nonhuman person.’ “

And that, perhaps, suggests that these intelligent animals — annually harvested by Native villages in carefully managed hunts — should be left alone.

Argument for Cetacean rights

White, Marino and others were part of Declaration of Rights for Cetaceans: Ethical and Policy Implications of Intelligence, a symposium held last weekend at the 2012 annual meeting of the American Association for the Advancement of Science in Vancouver. The discussion was inspired by an earlier conference that produced a 10-point “Declaration of Rights for Cetaceans.”

Over the past year, the group has been gathering supporters for the Declaration — which outlines how to countries ought to protect the “life, liberty and well being” and culture of the world’s cetaceans, including the rights of dolphins and whales to freedom of movement and “residence” in their natural marine habitats.

Dolphins and whales, the argument goes, are simply smart and sophisticated enough to deserve individual legal rights that would put them off-limits to being captured or killed by people.

“Under the declaration of rights for cetaceans … the animals would be protected as ‘non-human persons’ and have a legally enforceable right to life,” reported the London-based Guardian, in a story about the symposium. “If incorporated into law, the declaration would bring legal force to bear on whale hunters as well as marine parks, aquariums and other entertainment venues (that) would be barred from keeping dolphins, whales or porpoises in captivity.”

“The next step is taking the science and advocating for law in different places, from a regional point of view, from a national point of view, and eventually from a multinational and international view,” added presenter Chris Butler-Stroud, of the Whale and Dolphin Conservation Society, in the same Guardian story.

The arguments in favor bear little resemblance to broad positions taken by extreme animals rights groups but appear to be grounded on new scientific findings about the exceptional intellectual and social capacity of cetaceans — whales, dolphins and porpoises.

“A variety of scientific studies have found that whales and dolphins are capable of advanced cognitive abilities (such as problem-solving, artificial ‘language’ comprehension and complex social behavior), indicating that these cetaceans are far more intellectually and emotionally sophisticated than previously thought,” according to the symposium abstract. “Moreover, evidence is growing that for at least some cetacean species, culture is both sophisticated and important.”

Marino, in her presentation, laid out the growing body of evidence that the extraordinary smarts of cetaceans sets them apart from many other mammal species, putting them on par, in some respects, with primates like humans and chimps.

“They possess large complex brains second in relative size to our own and have demonstrated prodigious cognitive abilities in such areas as language comprehension, abstract thinking, problem solving, self-recognition and meta-cognition,” she wrote in the abstract to her presentation. “Many cetacean species rely upon complex social dynamics. Moreover, field studies over the past few years have revealed startling evidence for complex cultural traditions in many cetacean species, including orcas, sperm whales and humpback whales, to name a few. “

The evidence “argues for a major shift in human attitudes and treatment of them from commodities and resources to beings with a similar level of intelligence, self-awareness and sensitivity to our own,” she wrote.

“We’re saying the science has shown that individuality, consciousness and self-awareness are no longer unique human properties,” White told the Guardian newspaper in this story. “That poses all kinds of challenges.

“Dolphins are non-human persons. A person needs to be an individual. And if individuals count, then the deliberate killing of individuals of this sort is ethically the equivalent of deliberately killing a human being. The captivity of beings of this sort, particularly in conditions that would not allow for a decent life, is ethically unacceptable, and commercial whaling is ethically unacceptable.”

What about Alaska marine mammals like belugas?

Last weekend’s symposium was not specifically focused on Alaska marine mammals nor the ethics of subsistence harvesting of animals like belugas, in the same broad family of toothed cetaceans as killer whales and dolphins. But Alaska Dispatch queried White and asked how the same positions might apply to the hunting and killing of whales for food. White’s positions have also been laid out in the book, “In Defense of Dolphins: The New Moral Frontier,” and on a website of the same name.

“Specifically as your questions relate to bowheads and belugas, I get to plead ignorance,” White replied. “As a philosopher, I have to be very careful about what I claim to know about the scientific literature, and, until very recently, my focus has been exclusively on dolphins (but keep in mind that orcas are dolphins).”

Still, dolphins, no matter the species, have “sophisticated intellectual and emotional abilities” that include self awareness, personalities, abstract thought — traits that used to be considered unique to humans, White said.

“I can say unequivocally that based on what is known about dolphins, the deliberate killing of an individual dolphin is the ethical equivalent of an individual human because both have what philosophers refer to as ‘moral standing’ due ‘persons,'” he told us.

“Let’s assume for the sake of argument that bowheads and belugas have these traits. If so, the answer is straightforward.”

But isn’t the harvest of beluga and bowhead whales, along with other subsistence activities, a mainstay of village life along coastal Alaska?

Say belugas and bowheads came to be considered “nonhuman persons” who could no longer be hunted. Wouldn’t the cessation of the whale harvest cause immense harm to a Native culture already under siege from dislocation, poor nutrition, climate change, erosion, alcoholism, domestic violence and poverty?

In his email message, White acknowledge that applying their ethical arguments for cetacean rights to subsistence hunting by Alaska Natives or other aboriginal people raises enormously difficult issues.

“The plight of the tribes you describe, as is also true of the Native Americans and First Peoples elsewhere, is almost entirely the fault of the Europeans, Americans, etc. who have steamrollered over them, pushed them around and discriminated against them for centuries,” White wrote. “They did absolutely terrible things on this score, and the small number of people trying to protect what’s left of their cultures have a very difficult job. So from that point of view, they deserve our sympathy and respect.”

But science evolves, and with it, our understanding of the natural world and the capacities of the highly intelligent non-human species on Earth.

“Just because a culture has persisted over time, this doesn’t mean that all of its traits are ethically acceptable,” White said.

“In our case, we’re arguing that the progress of science over the last 50 years has taken us to the point where cultural practices that seemed ethical in the past now look different. That’s a challenge for Sea World. That’s a challenge for the Japanese. It’s also a challenge for the peoples you refer to.”

“However, in the case of any peoples who are already under special stress because of the way they’ve been treated by the whites, it is the whites who bear a special responsibility about providing the resources to make it possible for these communities to have healthy conditions in which to live at the same time that the rights of cetaceans are respected. Otherwise, this is just the latest example of those peoples being pushed around and being harmed because the dominant culture has the muscle to do so.”

Contact Doug O’Harra at doug(at)alaskadispatch.com

For more stories from Alaska Dispatch, click here.