Is the Holman print program worth saving? – The evolution of the arts economy in Canada’s North

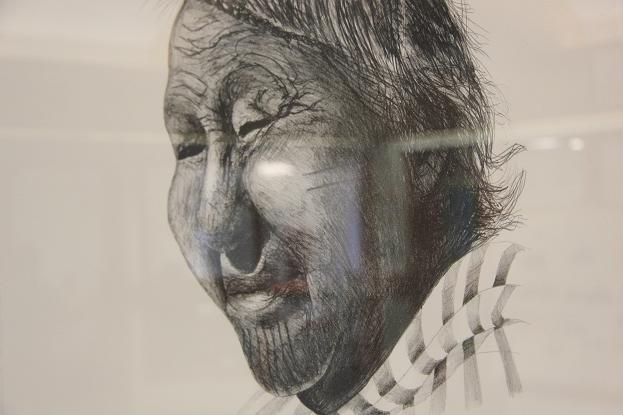

ULUKHAKTOK (Holman), Northwest Territories – Louie Nigiyok, a printmaker and artist from this remote Inuit community in Canada’s western Arctic, starts his days pretty much the way that he always has since the 1980s.

He wakes up and makes his way to the local print studio, now housed at the Ulukhaktok Arts Centre.

After sweeping and tidying up, Nigiyok passes through the centre’s gift shop, where his drawings and print works are displayed, to the centre’s drawing studio.

Large portrait windows rim the room, offering a stunning view of the surrounding landscape, and flooding the studio with natural light.

Nigiyok pulls an unfinished polar bear drawing from the top of a cabinet and spreads it out on a nearby table. Like most afternoons these days, he’s the only artist in the centre. As the afternoon wears on, he works silently, alternating between staring out the window and peering intently at the drawing, sketching and shading.

“At the beginning it was both the money and the art that interested me,” Nigiyok says of his first foray into the local printmaking program in the 1980s. “But now a lot of times it’s more of a hobby than a job because it’s fun to do. I love it.”

The only thing missing nowadays, he says, is that the community’s other printmakers and artists no longer feel the same way.

The Holman Collection

Ulukhaktok, known as Holman until 2006, has a proud artistic history. Catholic missionary Father Henri Tardy started a print and drawing program and founded the Holman Eskimo Co-operative in the 1960s.

By 1980s, this community, then numbering approximately 300 people, was one of the most vibrant art-producing centres in the Canadian North.

In 1980, it was decided that an annual print collection would be issued, something that brought the community wide acclaim.

Holman artists like Mark Emerak and Helen Kalvak gained national and international reputations.

Kalvak was made of member of the Royal Canadian Academy of Arts and even went on to receive the Order of Canada, the country’s highest civilian honour, for her contributions to the visual arts.

Nigiyok remembers these times vividly: the bustle as they produced and selected the 20 or 30 images that would make up the collection and then the editioning each of those images into 35 prints.

“Each print collection at that time had an international reputation,” Nigiyok says. “We were working side by side with a good group of artists and deciding how the print should be done. That was the most exciting part.”

End of an era

But times have changed.

The annual print collection was discontinued in 2000. The way locals tell it, contributing factors included lack of funding and difficulties in hiring and maintaining an in-house art advisor.

And though the Ulukhaktok Arts Centre opened in 2010 with carving, sewing and drawing studios where locals could make crafts for sale, efforts to restart the print program and annual collection have so far been unsuccessful.

“After 10 years of closure, we tried to re-open it again,” Nigiyok says. “We tried to get the printmakers and artists back in but they’ve lost interest. They have no energy left because everything was closed too long.”

A printmaking workshop organized to reunite the old printmakers and artists in 2011 didn’t fare any better.

“There was only one artist left out of a dozen,” Nigiyok says. “You can tell right there that the interest is lost.”

But despite these setbacks, Nigiyok hasn’t given up hope. He says the print program and annual collection were too important to Ulukhaktok to give up on and he’s determined they’ll find a way to bring them back.

Evolution of arts in the North

Arts production in the Canadian North has a long history. When the Canadian government began settling the semi-nomadic Inuit into permanent communities in the mid-1900s, they also began encouraging arts production as a way to encourage economic self-sufficiency among the Inuit.

The Canadian Craft Guild was established and the federal government invested in purchasing art and putting arts and crafts officers into communities in what is now the Northwest Territories and Nunavut.

“Arts and crafts was one of the few industries Inuit could participate in without speaking English,” says Karen Kabloona, director of tourism and cultural industries for the government of Nunavut, a territory in Canada’s eastern Arctic. “Inuit were asked to put their stories onto paper or into carvings and the economy grew from there.”

Art buyers and collectors in Canada, and internationally, clamoured for these depictions of traditional Inuit life. And works, especially carvings made from stone or bone, became extremely popular.

Arctic Co-operatives Ltd now sell everything from snowmobiles to groceries, but they were initially set up as a place to buy and sell these crafts and distribute the profits in the communities.

“Many of the community-based co-operatives in today’s Nunavut and Northwest Territories actually began as producer co-ops,” says Debbie Moszynski the vice president of Art Marketing for Arctic Co-operatives Ltd. in Winnipeg, Manitoba. “The establishment of the first local co-ops was really established through art marketing.”

The print programs set up across the Arctic had varying success. But those in Holman, Northwest Territories, Baker Lake, Pangnirtung and Cape Dorset, in what is now Nunavut and Puvirnituq, in Nunavik, Northern Quebec earned wide acclaim.

The annual print collections quickly became the communities’ calling card and gave the artists and collections cachet in the southern art market.

However, like in Holman, the print programs in many of these communities have petered out. And although the Cape Dorset print collection remains strong and has an international reputation, and the Uqqurmiut Arts Centre in Pangnirtung has begun reissuing its annual collection, in other areas of the Arctic, the programs have faded from memory.

In the community of Baker Lake, Nunavut, about 1150km away from Ulukhaktok, the arrival of the Meadowbank Gold Mine in 2010 offered unrivalled employment opportunities and stability for locals, meaning the employment and retention of artists and printers became almost impossible.

Even in Cape Dorset, with the success and travel opportunities afforded by a career in the arts, they are having problems adjusting. While the works from the stable of mid and late career artists continue to sell for hundreds and thousands of dollars down south. Cultivating a new stable of artists is proving more of a challenge.

Looking ahead

Those looking to restart the Holman collection may face similar challenges.

The local high school is named after Helen Kalvak. Her Order of Canada and the certificate marking her induction into the Royal Academy of the Arts hang in the lobby. Dozens of framed prints line the school hallways. But despite these markers of Ulukhaktok’s famed past, most students just shrugged their shoulders when asked whether they were eager to follow in Kalvak’s footsteps.

However, despite the challenges of cultivating the next generation of artists in communities like Ulukhaktok, and the increased importance of mining and resource development in the North, the economic and cultural role of arts and crafts in the northern economy shouldn’t be underestimated, say experts.

Arctic Co-op’s Debbie Moszynski says they continue to buy around 4000 pieces of art work annually from artists.

“We are certainly seeing fewer new artists coming to market but those that are, are very creative and helping to sustain Inuit art work,” she says.

The financial and cultural impact

In the Northwest Territories, arts and crafts from its Inuit and First Nations communities, including artworks, beading and carvings, put around six million dollars into the territory’s economy.

And while arts and crafts may just be a fraction of the hundreds of millions of dollars that mining and resource development bring into the North, its role in the economy shouldn’t be overlooked says Kevin Todd, director of investment and economic analysis for the Northwest Territories Department of Industry, Tourism and Investment.

“The thing with big resource developments is that it’s very specific in terms of location. And where the deposit is, is not necessarily where the people live or where people visit.”

The Northwest Territories population of 42,000 people is spread out among the territory’s 33 communities. About half of the population resides in the capital city of Yellowknife. But outside that, 90 per cent of NWT’s other 32 communities are aboriginal ones, often in remote locations.

“People want to live in their home community and they need a way to earn income,” Todd says. “That’s where their families are, that’s where they’re being educated.

“From both a cultural and an economic point of view, arts and fine crafts are important. They help pass culture from generation to generation.

“They’re economically important because it brings a lot of cash into communities that otherwise don’t have a lot of opportunities there. If you can create something with arts and fine crafts and also create opportunities in a traditional economy, those things together can generate a fair amount of cash income.”

Nunavut’s Karen Kabloona agrees. Arts and crafts continue to bring in around $23- million annually into Nunavut’s economy. And while the government welcomes mining and resource development for the employment opportunities they provide, she says maintaining an arts and crafts industry is equally important in order to provide the predominantly Inuit population of the territory an important choice.

“It suits our Inuit lifestyles,” Kabloona says of the flexibility arts and crafts production gives producers to schedule their work outside of hunting season. “It’s especially important in our smaller communities where there’s limited industrial options or office work and where people may want to maintain a traditional lifestyle and spend more time out on the land.”

“We’ll continue investing in arts and crafts because it’s a vehicle for cultural expression, cultural identity. It’s good for the soul. It’s good for tourism. There’s a lot of very good reasons to continue to invest in arts and crafts besides that it’s an important industry for people that chose not to work in mining or other industries or for government.”

And while it may appear anecdotally that younger people are less interested in the established drawing and print programs in places like Cape Dorset or Baker Lake, Kabloona says she’s not worried, pointing to the photography, video and digital art increasingly being produced in the territory.

“Young people growing up today are living a very different life from their parents and grandparents but I think the art industry will continue. Very exciting things are happening with young people and their expression through art. I think that will appeal to the same audience that Nunavut art has always appealed to.”

The future of the Holman collection

So what are the chances that Louie Nigiyok will see the Holman annual print collection restarted?

NWT’s Todd says it’s important to maintain historical traditions like the Holman Collection. Once community interest is there, like with initiatives in the territory’s other communities, the government is ready to support it, he says.

Now all Nigiyok has to do, is find a way to drum up that interest.

Nigiyok says there’s a three-year plan to restart the print program. The plan envisions employing a full-time art advisor and would involve the local high school to try to train a new generation of artists.

Nigiyok says they’ve applied for funding through the Northwest Territories Business Development and Investment Corporation and are waiting for an answer on a grant request.

“It will be good for the community. It will put us back on the map again,” he says. “Our culture is slowly dying and within the next 20 years, who knows what will happen? We try to keep our culture alive through our art, through cultural figures in the prints.”

But even if everything works out, getting things up and running will take time, he says.

“You can’t learn art overnight,” he says. “It’s a long process and it takes a while to get to where you want to be. The only way to get a print collection going up again is having motivated artists willing to come in every day for six months of the year.”

“(Our print program) should never have died off in the first place. It’s taking us a long time to get it up and going again… but I hope the young people will continue it.

“I’m getting drained just like the rest of the old artists so it’s time for some fresh blood.”

This story is part of Eye on the Arctic’s Arctic Art series.

Write to Eilís Quinn at eilis.quinn(at)cbc.ca