U.S. polar bear conservation plan focuses on near-term goals

The federal agency that manages polar bears concedes the most important action needed to protect the threatened animals – reduction of global greenhouse gas emissions to curb Arctic warming that is thinning sea ice – is beyond its powers.

So a polar bear conservation management plan, issued in draft form Thursday by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, focuses instead on actions the agency says it has the ability to accomplish.

“Addressing climate change will take a global commitment but in the meantime the Fish and Wildlife Service and its partners are committed to do everything within our control to give the bear a chance to survive while we await global action,” the agency’s Jenifer Kohout, a co-chair of the team who wrote the plan, said in a teleconference.

Cooperation with Russia

The plan calls for enhanced international conservation work, including with Russia; better management of bear-human conflicts, likely to become more frequent as loss of sea ice drives more polar bears to land and the food sources there; protection of denning habitat, which is increasingly on land instead of on sea ice; protections for polar bears from oil spills, a growing risk as offshore oil development and shipping increase in the Arctic; and better management of the Native subsistence hunt through a tiered system that could allow hunting restrictions when bear subpopulations dwindle.

Nonclimate stressors are “not unimportant,” but eliminating them would bring only a relatively small benefit to polar bears, said Todd Atwood, a U.S. Geological Survey biologist, polar bear expert and member of the conservation plan team. “The driving force is projected sea-ice decline and loss of sea-ice habitat,” he said.

The conservation plan does call for limited agency action on greenhouse gas emissions and climate change. It calls for the Fish and Wildlife Service to do more to explain to the public how polar bears are being hurt by human-caused climate change, to support actions to address human-caused Arctic warming and to continue an internal campaign to become carbon-neutral by 2020.

Greenhouse gas emissions

Polar bears, when listed as threatened in 2008, became the first animals granted Endangered Species Act protections because of global climate change.

If greenhouse gas emissions continue on their current trajectory, according to new research by the USGS, polar bears will decline dramatically around the circumpolar north, except in the ice-sheltering Canadian Arctic archipelago.

“They’ll be still around. But if we do nothing about greenhouse-gas emissions, by the end of the century they’ll be a fraction of the population that they are now and they’ll be in a fraction of the range,” said Atwood, who co-authored a threat-assessment report used to craft the polar bear conservation plan.

Such a fate would bode ill for areas far to the south, Atwood said. “Polar bears are just a sentinel for broader global changes that will happen beyond the Arctic,” he said.

Carrying out the plan would cost the government $12.9 million over five years, according to the U.S. Interior Department.

Input from industry, indigenous peoples

The draft plan released Thursday was crafted in accordance with the Endangered Species Act and the Marine Mammal Protection Act. It is the U.S. contribution to an emerging circumpolar strategy on polar bear preservation, with contributions from Canada, Russia, Norway and Greenland and based on past international agreements.

It is subject to a 45-day public comment period.

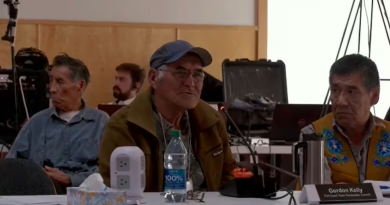

Alaska Native subsistence hunters, the oil industry and the state of Alaska, which have challenged federal polar bear policies – and even the threatened listing itself – were represented on the plan team.

With such broad participation, the result was a consensus, said Mike Runge, a USGS research ecologist who helped chair the group.

“This was really a collaborative effort by a broad group of stakeholders with very different interests and goals around a lot of issues but a common desire for polar bear conservation,” Runge said in the teleconference. Members “tried very hard to make sure that the issues that might cause dissent were talked about openly and discussed from many angles,” he said.

The Alaska Oil and Gas Association, an industry’s trade group represented on the plan team, is satisfied with the outcome, executive director Kara Moriarty said in a statement. “Striving to create and adopt strategies that benefit the viability of the polar bear species while affording the State of Alaska to pursue economic interests in the Arctic benefits a wide variety of stakeholders in addition to polar bears,” Moriarty said.

The Alaska Nanuuq Commission, a Native subsistence hunting organization, was also represented on the plan team.

“In the words of our founder Charles Johnson, when we lose polar bears, we also lose our cultures,” Jack Omelak, executive director of the commission, said in a statement released by the Fish and Wildlife Service. “Our people are natural conservationists and have practiced taking only what is needed for centuries. We treat polar bears and their habitats with reverence. Now, we are looking to our global community to do the same.”

Mixed reactions

Environmentalists had mixed reactions to the plan.

Margaret Williams, director of the U.S. Arctic program at the World Wildlife Fund, said it is “commendable” the Fish and Wildlife Service was clear in its statements about greenhouse gas emissions and climate change.

But with Royal Dutch Shell poised to resume drilling this year in the Chukchi Sea, more detail is needed about development impacts, she said. “The most immediate threat that we think that can be tackled is the potential for oil spills,” she said.

The Center for Biological Diversity, the environmental group that submitted the original petition to list the polar bear, said the conservation plan falls far short of what is needed to help polar bears.

“When it comes to the carbon pollution melting the polar bears’ Arctic world, this plan just shrugs and hopes for the best,” Rebecca Noblin, Alaska director at the center said in a statement. “The science shows clearly that deep greenhouse gas reductions are needed to save polar bears from extinction, but the Obama administration doesn’t lay out a clear plan for what those targets should be and how to get there.

“Without specific targets we’ll see more and more polar bears drowning and starving to death.”

Alaska Dispatch News reporter Kamala Kelkar contributed to this article.

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: Study shows polar bears relocating to icier Canadian Archipelago, Eye on the Arctic

Finland: Finland’s bears are on the move, Yle News

Russia: Submariners feed polar bears with garbage, Barents Observer

Sweden: Petition to restrict brown bears in North Sweden, Radio Sweden

United States: Scientists seek cause of patchy baldness in some Beaufort Sea polar bears, Alaska Dispatch