Climate-driven Arctic permafrost thaw will dramatically alter northern landscapes: study

Rapid climate-driven permafrost thaw in huge swaths of the Arctic will dramatically change northern landscapes in the same way landscapes in southern Canada changed after the last Ice Age over 13,000 years ago, according to new Canadian research.

Similar processes are also underway in Alaska, as well as areas of the Russian Arctic and Siberia, said Steve Kokelj, a permafrost scientist at the Northwest Territories Geological Survey.

Kokelj is the lead author of a study published in February 2017, in the journal Geology, titled Climate-driven thaw of permafrost-preserved glacial landscapes, northwestern Canada.

“Permafrost is the geological manifestation of climate, it’s frozen ground,” said Kokelj. “And in the North much of the ground is frozen, and permafrost can be hundreds of meters in thickness.”

The permafrost temperature varies, from very cold permafrost in the Arctic to very warm permafrost further south, Kokelj said.

“What we are particularly interested in as scientists is understanding which permafrost contains ice because if there is lots of ice in the ground and that permafrost thaws, then the terrain will subside and the landscape will change as function of how much ice there is in the ground,” Kokelj said.

Kokelj and his research group studied so-called thaw slumps, landscape features where the icy permafrost starts to thaw.

“And these disturbances kind of chew their way up across the landscape as the ice melts,” Kokelj said.

These features are becoming very large and they’ve grown particularly rapidly over the last 20 years driven by climate change, Kokelj said.

Some of these thaw slumps in the Mackenzie Delta region occupy an area of 20 to 30 hectares and they’ve displaced millions of cubic metres of materials, Kokelj said.

“And we have good evidence that this is not something that has been common in the last 100 or 1,000 years,” he said.

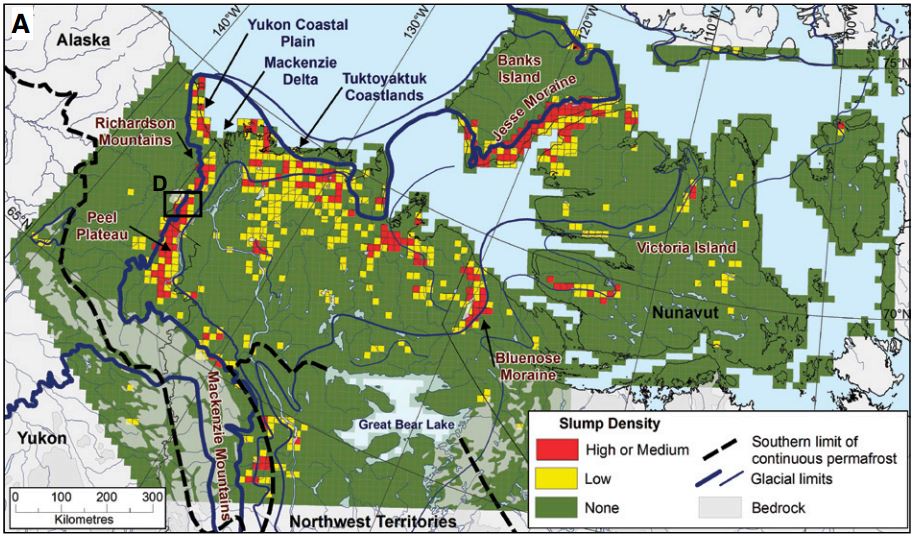

Kokelj and his team of researchers at the NWT Geological Survey mapped the distribution of these thaw slumps over a 1.2 million square kilometre area of northwestern Canada using satellite images and other data, as well as studying the landforms deposited at the ice edge of the former Laurentide Ice Sheet (LIS), the immense glacier that covered most of Canada during the last Ice Age, 15,000 years ago.

“And what the pattern was that emerged was this heat map and it showed very clearly that the distribution of these disturbances was bounded by the limits of the continental glaciation, which covered almost all of Canada as recently as 13,000 years ago,” Kokelj said. “The limits where we find these thaw slumps is very-very well constrained by the limits of the ice sheet.”

A conservative estimate is that these disturbances affect landscapes over an area exceeding 136,000 square kilometres, Kokelj said.

When the ice sheet retreated thousands of years ago, it created huge landscape disturbances and in southern Canada big transitions happened 13,000 years ago, Kokelj said.

“In the North, as the ice sheet retreated, permafrost essentially preserved a lot of this ice that was either buried or formed in that very dynamic environment at the front of the ice sheet,” Kokelj said. “And this ancient ice has been preserved for over 10,000 years and the changes that transformed the southern landscapes, some of those changes haven’t occurred in the north yet. And the climate-driven thaw that’s occurring now is manifested by very significant changes in these particular landscapes.”

This means that some landscapes have an inherent potential for dramatic change in the future, he said.

And some of the landscapes that are changing most rapidly are the more northern landscapes, Kokelj said.

“That seems counterintuitive because the permafrost should be very cold in the most northern settings but what in fact has happened is that ice has been best preserved in those coldest environments, so the potential for change is actually the greatest,” Kokelj said.

These same transformative processes occurred in the southern latitudes thousands of years ago but that process was delayed in the North because the climate stayed relatively cold and the permafrost has preserved a lot of that ice from the retreating Laurentide Ice Sheet, Kokelj said.

“These landscapes are poised to change,” he said.

And these landscape disturbances are also changing the chemical composition of northern streams and rivers as millions of tons of this carbon-rich sediment are carried away downstream with the thawing permafrost, he said.

Understanding these landscape changes is critical for figuring out how to be best adapt to and mitigate the future impact of climate change, Kokelj said.

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: Canadian river carries carbon from thawing permafrost to sea, Alaska Dispatch News

Finland: Climate change brings new insect arrivals to Finland, Yle News

Greenland: Can we still avert irreversible ice sheet melt?, Deutsche Welle’s Ice-Blog

Norway: UN Secretary-General to visit Norwegian Arctic, Eye on the Arctic

Russia: Ancient virus found in Arctic permafrost, Alaska Dispatch News

Sweden: How will global warming affect the average Swede?, Radio Sweden

United States: New permafrost map shows areas in Alaska vulnerable to thaw-induced collapses, Alaska Dispatch News