Blog: Can environmental diplomacy save Arctic languages?

Following a 2008 symposium on indigenous arctic languages in Tromsø, Norway, the Indigenous Permanent Participants of the Arctic Council launched the Arctic Languages Vitality initiative under the auspices of the Council’s Sustainable Development Working Group. Envisioned as an Indigenous-driven project supporting the vitality of the sixty or so languages native to the Arctic, the initiative has been stalled since a February 2015 progress report.

Some of the delay has been attributed to funding complications at the end of Canada’s 2013-2015 Arctic Council Chairmanship and to a lack of leadership among the Indigenous groups. Kickstarter funding from the Canadian Government and supplements from the Saami Council and the US National Science Foundation allowed the establishment of general project coordination and several representative and expert meetings, but this dried up before resources could be allocated to on-the-ground revitalization activities in Arctic communities.

Not a simple matter

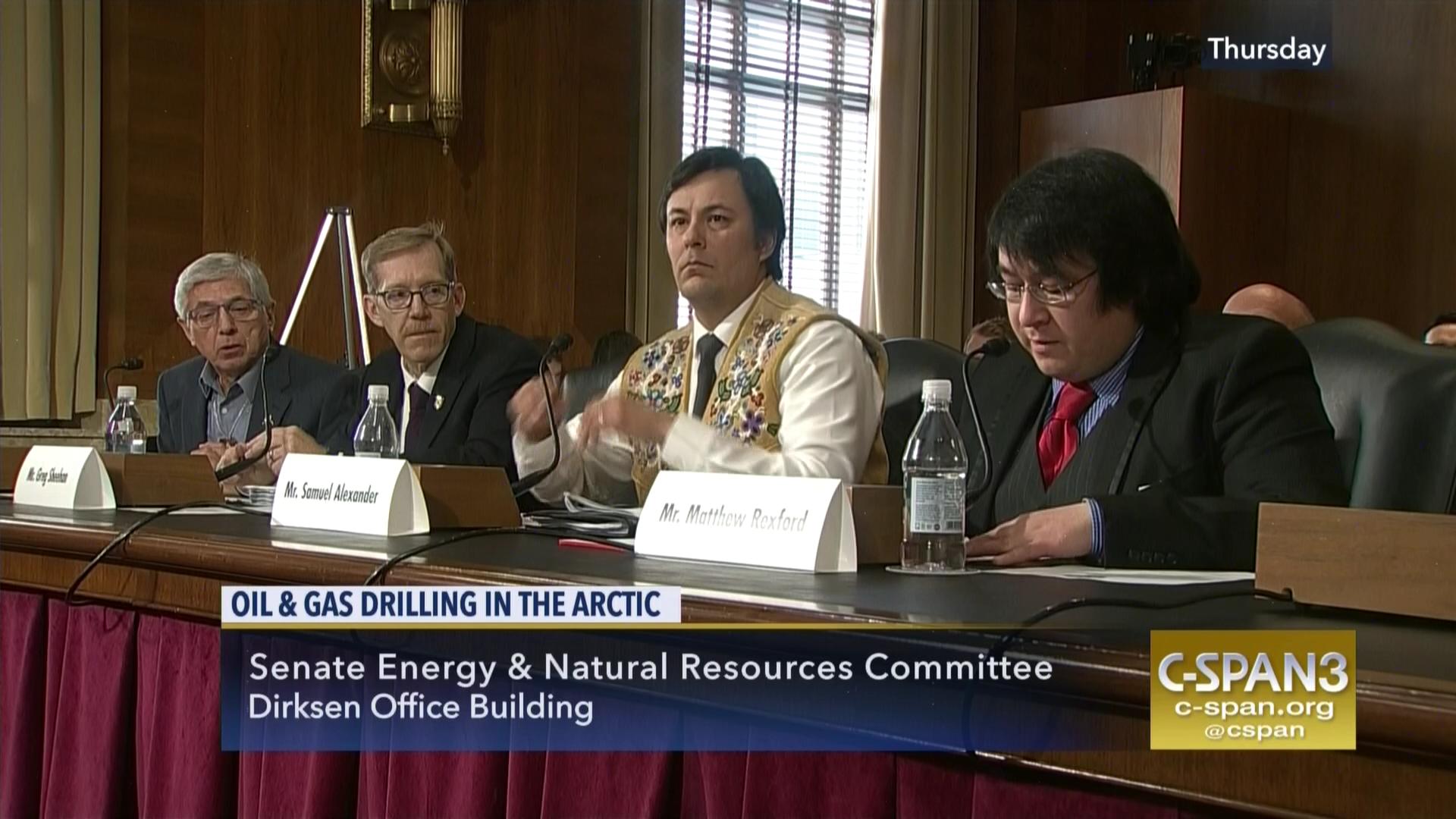

This isn’t surprising, given the complicated nature of financial continuity in an eight-member intergovernmental body with rotating two-year chairmanships. Neither is it a simple matter to coordinate leadership structures among six Indigenous groups with frequently conflicting positions, such as Gwich’in and Iñupait representatives’ comments in the recent U.S. Senate Committee on Energy and Natural Resources hearing on oil and gas exploration and development in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge. That’s just within Alaska, and the permutations of opinion among communities across the greater Arctic are even more complex. One thing all Arctic Indigenous communities share, however, is a high degree of language endangerment (with the notable exception of Greenlandic/Kalaallisut), occurring alongside ecological changes in their traditional lands.

These two challenges are more intertwined than most would expect. “When languages die, ecosystems often die with them” read the headline of a 2014 article running as part of Public Radio International’s Living on Earth series. Languages are delicate social repositories of human knowledge. This knowledge is critical to the management of ecosystems and environmental management practices are bound up in the ways people say things about places. In turn, traditional subsistence activities often provide a source of resilience for endangered languages that would otherwise become victims to colonial assimilation. To summarize: Language death begets species death and species death begets language death.

Dialogue a necessity

While academia has discoursed these processes to obscurity, broad-based civic dialogue is necessary if one is to expect any sort of high-level political will to change things for the better. This involves a pointing of moral fingers: who are the historically responsible parties, and who should pay for the prevention of further ecolinguistic degradation? The perpetrators of imperial-style linguicide of the 19th-Century variety, for example, can thus easily be blamed for some degree of ecological destruction. Similarly, it is often possible to identify clear causes for the species extinctions that lead Indigenous communities to reduce the amount of time devoted to traditional subsistence activities and turn instead to putting food on the table through increased participation in wage labor markets dominated by colonial languages.

The need for more complicated moral gymnastics arises when trade-offs and disputes between communities need to be settled. In the Arctic specifically, for example, sources of revenue that may fund mitigation efforts in one community may have negative spillover effects elsewhere via a linked system. For example, local services to extractive industries may provide the revenue that funds language nests and other programs in one area, while the environmental damage linked to those revenue streams may reduce the ability of a neighboring community to hunt or fish.

Language vitality and ecosystem health

The relationship between language vitality and ecosystem health in the Arctic has been examined and assessed by academia and intergovernmental bodies such as the Arctic Council’s Conservation of Arctic Flora and Fauna (CAFF) Working Group in its 2013 Arctic Biodiversity Assessment. When it comes to management, however, regional, national and international governance mechanisms that affect conservation and language use globally do not usually make it easy to address the issues in a holistic manner. Fortunately for the Arctic, cross-pollination has been increasing despite an organizational cleft among Arctic Council Working Groups that to some degree reflects traditional silos of institutionalized knowledge. One clear example is the repository of linguistic and languages data in CAFF’s Arctic Biodiveristy Data Service.

Project opportunities

Whereas the resolution of disputes between communities is a political matter, the Arctic Council’s Working Groups can be compared to governmental science agencies providing the data against which value judgments are weighed, or to a civil service dutifully dedicated to constitutional continuity through waves of political change. Although the extent to which Arctic Council Chairmanships are politicized among member countries is also relatively low, each two-year mandate provides the chair country with an opportunity to invigorate certain projects and initiatives according to its own international and domestic priorities, with resources that are sometimes overlooked until chairmanship planning begins.

Supporting the vitality of Indigenous arctic languages both for the purposes of environmental functionalism and for the direct social benefits for the communities that speak them would help Iceland live up to its reputation for unorthodox problem-solving in support of its Arctic Council ambitions. As all chairmanships have since the 1996 establishment of the Arctic Council, Iceland’s upcoming 2019-2021 chairmanship is expected to place a strong emphasis on both environmental protection and human well-being. The degree to which the Icelandic Ministry for Foreign Affairs is able to coordinate its own departments and other relevant Ministries to these ends will determine how successful the two years are in the eyes of other Arctic countries and whoever else is paying attention.

Part 2 of this series, Arctic languages survival – Iceland to the rescue? takes a deeper look at Iceland’s role in the politics of language revitalization and environmental conservation.

***

Takeshi Kaji is the Director of the Arctic Circle Secretariat in Reykjavík, Iceland. The Arctic Circle is a non-partisan organization dedicated to open, democratic dialogue on the future of the Arctic. The views expressed in this article are those of the author alone.

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: Inuit in Canada and Greenland seek co-management of crucial Arctic habitat, Radio Canada International

Finland: Sami group occupies island in northern Finland to protest fishing rules, Yle News

Greenland: `Enough of this postcolonial sh#%’ – An interview with Greenlandic author Niviaq Korneliussen, Eye on the Arctic

Norway: Establishment of Álgu Fund marks new beginning in Arctic Council, indigenous peoples say, The Independent Barents Observer

Sweden: Treatment of Sami people among Swedish shortcomings : Amnesty International report, Radio Sweden

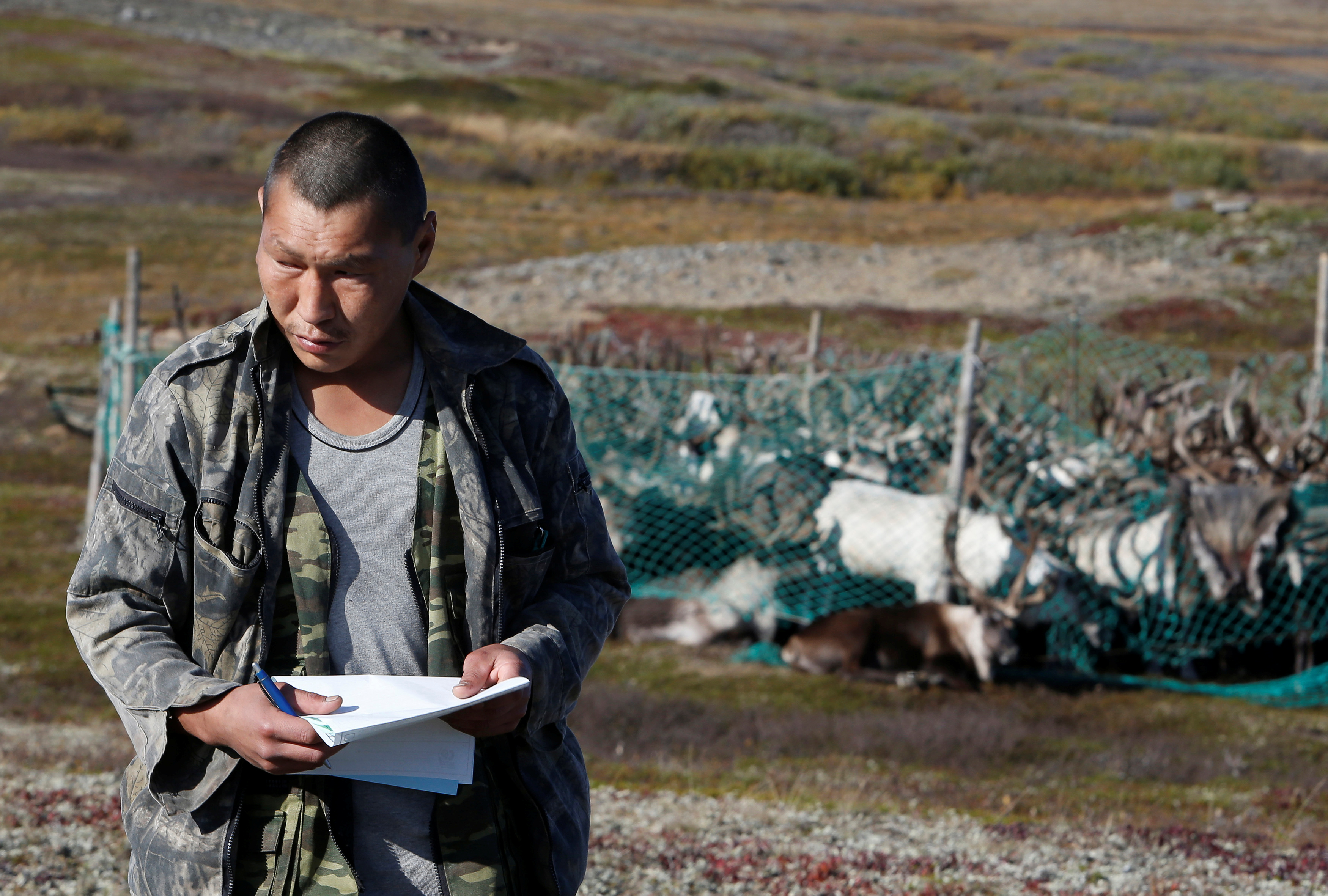

Russia: More protected lands on Nenets tundra in Arctic Russia, The Independent Barents Observe

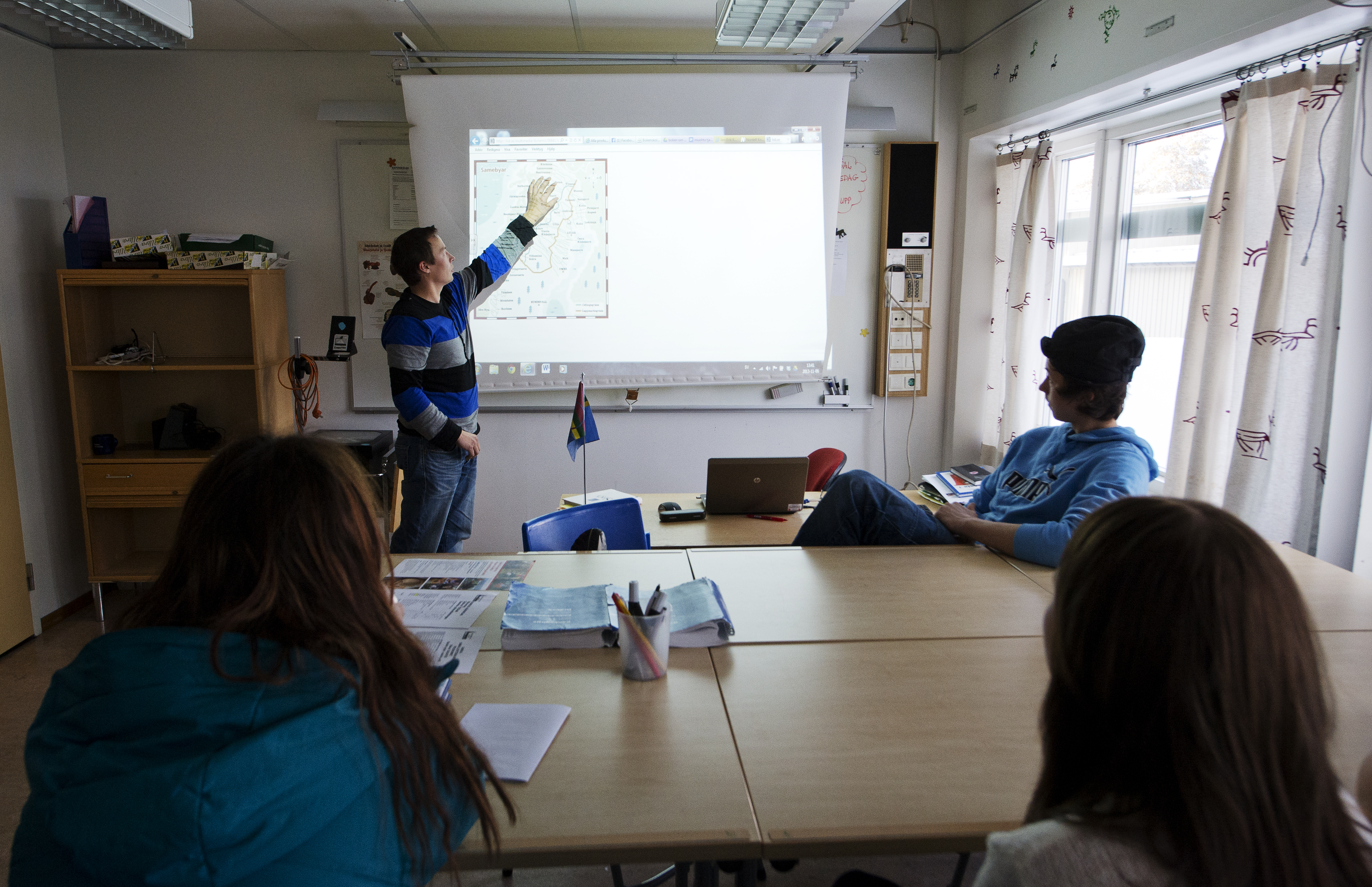

United States: Preserving Indigenous languages in Alaska, one grocery store at a time, Alaska Dispatch News