Canada files submission to establish continental shelf outer limits in Arctic Ocean

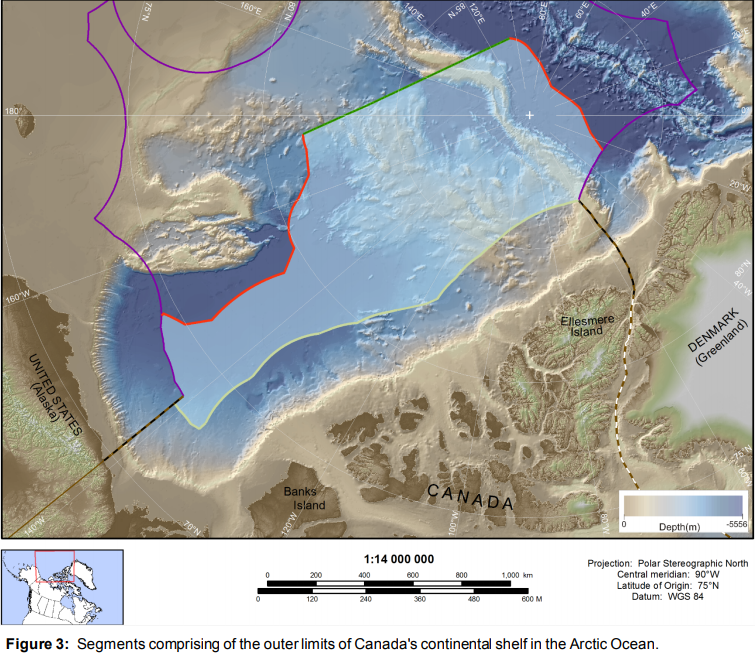

Canada filed its Arctic continental shelf submission with the U.N. Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf on Thursday, claiming approximately 1.2 million square kilometres of the Arctic Ocean seabed and subsoil in an area that includes the North Pole.

“Canada is committed to furthering its leadership in the Arctic,” said Chrystia Freeland, Canada’s minister of foreign affairs, in a news release. “Defining our continental shelf is vital to ensuring our sovereignty and to serving the interests of all people, including Indigenous peoples, in the Arctic.”

The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS) gives coastal states a 200 nautical mile continental shelf claim that allows countries the right to exploit resources in the seabed and subsoil of their respective areas.

The activities could be anything from deep seabed mining and fishing, to oil and gas exploration.

Canada has been working on gathering data to support its claims in the Arctic and Atlantic Oceans since 2003.

“We are proud to support Canada’s Arctic Ocean submission to the Commission on the Limits of the Continental Shelf, supported by science and evidence, reaffirming our government’s commitment to furthering Canada’s leadership in the Arctic,” Amarjeet Sohi, Canada’s minister of Natural Resources, said in the news release.

Overlapping claims

But UNCLOS allows continental shelves to be extended if a state has scientific data to prove that particular underwater geological or geographical features are actually extensions of their continental shelves.

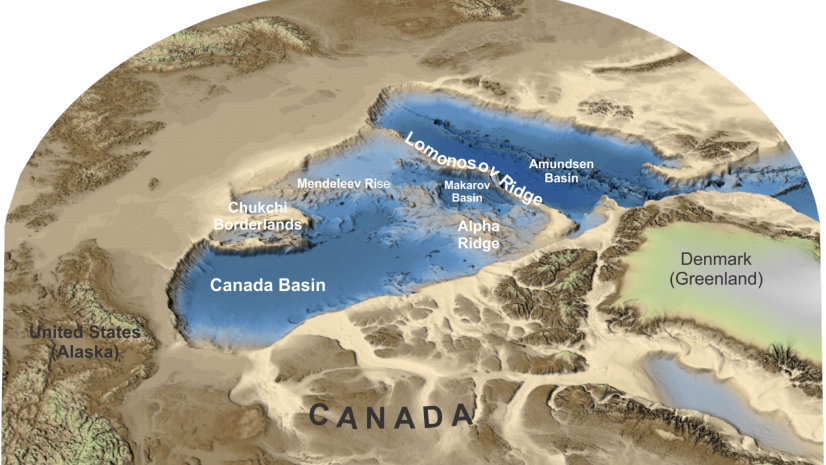

The Lomonosov Ridge is a kind of underwater mountain chain that extends across the seafloor of the Arctic Ocean and is something that Canada, Russia and Denmark all claim is an extension of their respective continental shelves.

Russia was first to make a claim in the area, stopping just short of the North Pole, in 2001. Denmark submitted its submission concerning the Lomonosov Ridge in 2014.

The commission rules on the validity of the science submitted by countries, which then becomes the basis for subsequent political discussions over jurisdiction.

Adam Lajeunesse, the Irving Chair at the Mulroney Institute of Government at St. Francis Xavier University in Nova Scotia, Canada, and a Research Fellow at the Canadian Global Affairs Institute, says Canada’s claim contained few surprises.

“There was (some conjecture) that we would sort of do a quid pro quo and stop our claim at about the pole as a means of facilitating a political settlement ultimately,” Lajeunesse said in a phone interview with Eye on the Arctic. “But like the Danes, we’ve gone well over the North Pole and are claiming an enormous chunk of the Arctic continental shelf now.”

The commission has already ruled that the geology data put for forth in Russia’s claim looks sound, but it could rule the same on Canada’s and Denmark’s data, says Lajeunesse.

“There’s a very real chance that all three countries will have put forth claims based on good scientific evidence. Ultimately this will be a political resolution, not something resolved by the United Nations.”

For more on UNCLOS, the Arctic and why the U.S. remains an outlier on this question, listen to more of Eye on the Arctic‘s conversation with Adam Lajeunesse, the Irving Chair at the Mulroney Institute of Government at St. Francis Xavier University and a Research Fellow at the Canadian Global Affairs Institute.

Climate driving state interest in boundaries

Climate change is warming the Arctic at more than twice the rate of the rest of the world and is driving increased economic and political interest in the North from the international community.

However, though headlines have long trumpeted an Arctic resource bonanza, Lajeunesse says whatever the final boundries end up being, the potential for resource extraction in this part of the world is overblown.

“Even if we find a huge amount of oil in this area, say around the North Pole, I tell people to keep in mind this about 2400 km away from nearest Canadian or Russian infrastructure,” he said.

“Over the last 10 years we’ve be trying to drill wells in the Chukchi Sea and the Kara Sea that are maybe 50 to 70 km from away from infrastructure, and those wells cost $10 billion.

“So the idea of us every really developing this region around the North Pole and ever actually mining it or getting oil and gas… I think that’s probably a fantasy and I think people shouldn’t overestimate the economic value of those resources, at least when they’re considering where all this is going. “

Canada’s submissions now complete

Canada ratified UNCLOS in 2013.

Canada’s Arctic Ocean continental shelf claim is the country’s last such submission. Canada’s Atlantic continental shelf claim was filed in 2013.

It has no continental shelf claims in the Pacific Ocean.

The commission will take at least 10 years before ruling on Canada’s Arctic Ocean submission.

Correction: A previous version of this story incorrectly said that Canada’s continental shelf submission was filed on Wednesday. The submission was made on Thursday. This version of the text has been corrected.

Write to Eilis Quinn at Eilis.Quinn(at)cbc.ca

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: Canada to file submission for its continental shelf limits in Arctic Ocean in 2019, Radio Canada International

Finland: Norway will not give away mountain peak, The Independent Barents Observer

Greenland: Canada and Denmark set up joint task force to resolve Arctic boundary issues, Radio Canada International

Norway: Norway and EU clash over rights to resource-rich waters around Svalbard, The Independent Barents Observer

Russia: Russia scores scientific point in quest for extended Arctic continental shelf, Radio Canada International

United States: U.S. to collect Arctic data for modern navigational charts, Alaska Dispatch News