Taloyoak band, Nickelback producer set up recording hub in Arctic community

For one week this winter, the quiet of Taloyoak’s Boothia Hotel was broken by the rumble of electric guitar.

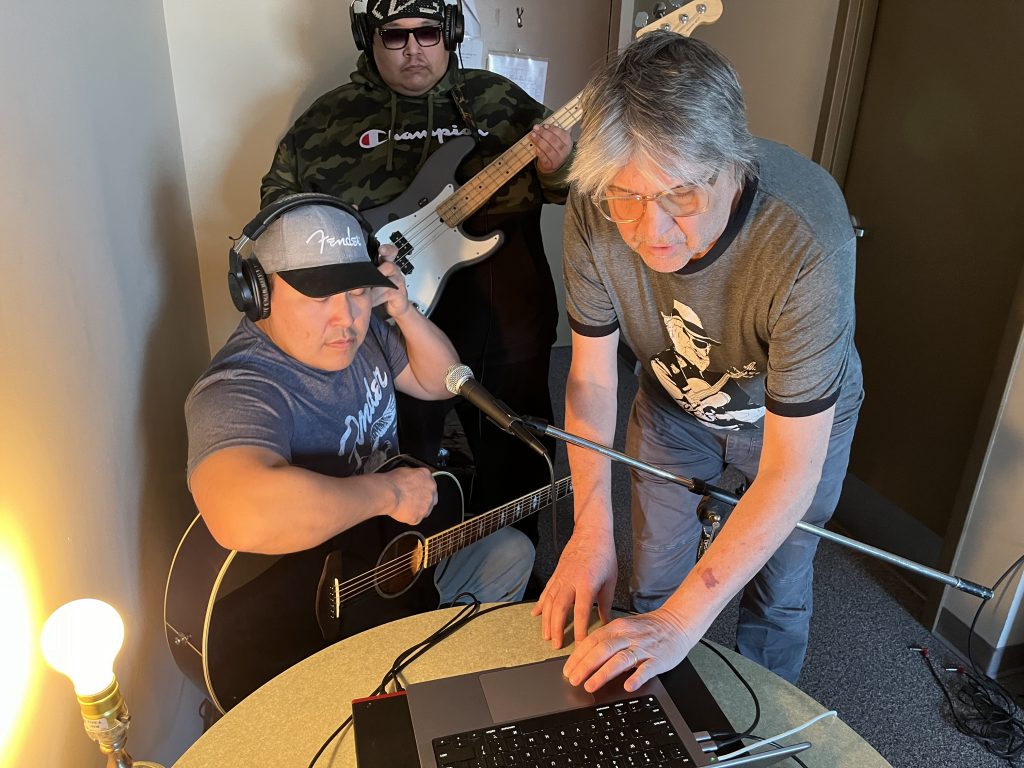

Every now and then, the music pauses, and the sound of animated voices cascades through the thin walls. It’s all coming from room seven, where something very special is happening: the local Taluqruak Band, along with Dale Penner, a producer best known for his work with Nickelback, are busy transforming the mess of wires, cables, cases, and computers into the northernmost music production hub on mainland Canada.

Drawing Inspiration from trailblazing Inuit musicians

Joe Tulurialik, the lead singer and guitar player, says the soundtrack to his childhood was pioneering Inuit musicians like the Uvagut Band from Iqaluit, and particularly those from northern Quebec, like Sikumiut from Puvirnituq and the Salluit Band from Salluit.

“I mostly grew up with my grandparents and they listened to a lot of CBC Radio where they’d play those songs,” he said. “That’s the style of music I grew up with and am still a fan of now.”

It wasn’t long he wanted to play music himself.

“My dad plays guitar and I grew up watching him sing and play at community events at Easter and Christmas time,” Tulurialik said. “Then at 12 years old I picked up the guitar and played my first public event six months later.”

Showcasing language through music

The Taluqruak Band traces its beginnings to the Anglican church in Taloyoak, where Tulurialik and his cousin Paul Ogruk led praise and worship services in their youth.

Today, the band consists of Tulurialik and Paul, along with Lloyd Saittuq on drums, Saul Kootook on lead guitar and background vocals, and Andrew Aiyout, who shares singing and guitar duties with Tulurialik.

Their setlist covers the Inuktitut-language music Tulurialik grew up with, as well as original compositions sung in Natsilingmiutut, an Inuit-language dialect of the region.

“We like English music but there’s already a lot of it out there,” Tulurialik said.

“We want to promote our very distinctive dialect and keep our language and culture alive. It’s very important to us.”

Distance challenges for Arctic musicians

The band often performs in the community and even at regional events. However, they say that the ongoing challenges of creating and sharing music from their remote location persist.

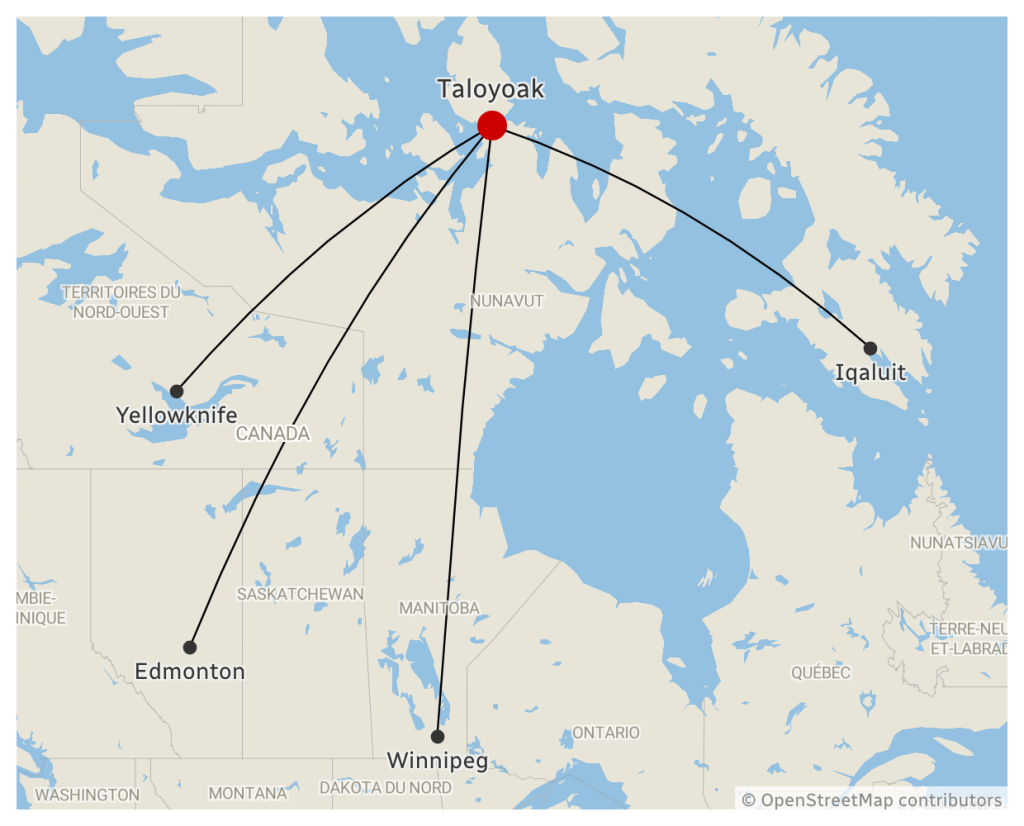

“People understand distances are long and the cost of living is high in Nunavut, but what people maybe don’t know is that here in the Kitikmeot Region we’re isolated even within Nunavut, and that here in Taloyoak, we’re remote even within the Kitikmeot Region,” Tulurialik said.

Tulurialik said he still remembers the thrill of once being selected to perform at Nunavut’s top musical event, the Alianait Arts Festival, only to be left disappointed when they couldn’t attend due to the costs of transporting the band from Taloyoak to Iqaluit.

“It’s not the first time something like that happened to us,” he said. “And it got me thinking, we don’t even have professional recording studios here—not just in Taloyoak, but not in any of the Kitikmeot communities— so we can’t get our music out when we can’t travel. But then I was like, OK, but what can I do about it?”

After careful consideration, Tulurialik found the answer: establishing studio space in Taloyoak. He believed the initiative would not only benefit local musicians but also the entire hamlet, facilitating the recording of traditional music, stories, and community events. Moreover, he envisioned the studio as a resource for artists in neighboring Kitikmeot communities, ultimately transforming Taloyoak into a musical hub for the region.

As an Inuit beneficiary, he knew there must be funding or grants available for cultural projects. But said he felt stumped by his lack of knowledge regarding where to start, whom to reach out to, and how to navigate the paperwork involved.

“I have a lot of passion but not a lot of education. I stopped school at 15 and don’t have a high school diploma. I have no problem doing the work, but I just needed direction on how to do it.”

Empowering northern talent

All that changed when Tulurialik saw Thor Simonsen, the founder of record label and touring company Hitmakerz, being interviewed on UvagutTV’s The Tunnganarniq Show about the company’s commitment to supporting and promoting Nunavut musicians.

Tulurialik immediately reached out to Simonsen to share his idea. Simonsen connected Tulurialik with Hitmakerz CEO Sarah Elaine McLay and over the next months they worked together on the proposal.

“Hitmakerz always wants to support creativity in the communities so artists can share their stories, strengthen their culture and create sustainable careers in music,” McLay said.

“Joe’s passion and vision about getting access to recording facilities not only for the community, but also for the region, just made Hitmakerz so excited to support this project.”

Nunavut’s Department of Economic Development and Transportation agreed to fund the project, with the Municipality of Taloyoak also signing on to donate time and space for things like equipment storage.

When it was time to choose who would go to Taloyoak to train the Taluqruak Band on the equipment and how to set it up, Hitmakerz said Dale Penner was an obvious choice.

Penner, originally from Manitoba, landed his first significant opportunity as a sound engineer on Loverboy’s Heaven in Your Eyes, one of the hit songs from the original Top Gun movie soundtrack. Following this success, Penner transitioned into production work, working with musicians like Econoline Crush, Holly McNarland and the Matthew Good Band. His big break came with producing Nickelback’s album The State and helping them secure their U.S. label deal with Roadrunner Records that made them global superstars.

“Dale Penner has decades of experience and has had great success recording and producing bands so he has a skill set very complementary for what Joe wants to accomplish,” McLay said.

North-South collaboration

Penner said that as someone that’s “never been further North than Winnipeg” he was initially unsure about taking the gig in the High Arctic, but that phone calls and Zoom meetings with Tulurialik convinced him.

“I was a little hesitant at first, and told Sarah to let me think about it,” he said. “But once I talked with Joe about what he wanted to do, it was his enthusiasm and my sense of adventure that got me here.”

Tulurialik said it was already a dream come true when he learned the project funding had come through, but when Hitmakerz told him Dale Penner was the person coming to set everything up and train them, he couldn’t believe it.

“I looked up the work he’d done with Nickelback and other famous bands down South, and I messaged all my bandmates and other people about it,” he said. “I just thought, ‘Wow, this guy is the real deal and he’s coming here to Taloyoak to teach me? What have I gotten myself into? It’s crazy.”

Penner said he’s got just as much out of the experience as the band has.

“It’s so chill and relaxed here and I’m learning so much,” he said.

“The level of their ability to play their instruments and sing and write melodies is very good. If you put aside the constraints on them like the distance of being in the Arctic, there’s no difference working with them, than there is with any other band.”

Adapting equipment demands to remote location

Putting together equipment for the Taloyoak Studios project required multiple conversations with Tulurialik and careful thought, Penner said.

Like in other Nunavut communities, Taloyoak grapples with insufficient housing and office facilities. With no opportunity for a permanent studio space, Penner knew he had to concentrate on light, streamlined and highly mobile equipment that the band could tear down and set up depending on if they were recording music in a home, or live performances at the community centre. Equipped with this gear, and a laptop running Avid ProTools, the most dominantly used software in professional music production, the project was ready to go.

Once the internet becomes more reliable in the North, Penner said musicians in Arctic Canada will be less disadvantaged when it comes to recording music and sharing it with the public.

“The pandemic changed a lot,” he said. “I live in Winnipeg but am mostly working with U.S. artists these days and a lot of that work is remote. I can record a track from one city. I can record another track from another and I can mix it all in my studio in Winnipeg.

“So what they could be doing up here is pretty much the same as the way a lot of people work these days. It opens access to the complete, global music community for musicians in the Arctic.”

Creative innovation in the Arctic

Tulurialik said he’s eager to make this vision a reality, especially in Nunavut. He said he envisions collaborative projects with other Kitikmeot musicians where a guitar player from Kugaaruk and a singer from Gjoa Haven, could all contribute tracks that could eventually be mixed in Taloyoak.

Tulurialik said he’s excited to see where the Taloyoak Studios project leads and is eager to share his story to let other Nunavummiut—inhabitants of Nunavut— know not to give up on their visions no matter how small or remote the community may be.

“I hope people hear this story and realize there’s so much creativity and ideas in our small communities, not just music but business and entrepreneurship too.

“Some of us may not be educated, but we make up for it with passion and creativity. We just need the information on how to get those ideas out there.”

Comments, tips or story ideas? Contact Eilís at eilis.quinn(at)cbc.ca

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: Connecting through culture—How Isaruit became a haven for Ottawa Inuit, Eye on the Arctic

Finland: Sami joik, symphonic music fusion from Finland makes int’l debut in Ottawa, Eye on the Arctic

United States: How Inuit culture helped unlock power of classical score for Inupiaq violinist, Eye on the Arctic