Gradually, one reunion at a time, the healing continues.

For a number of years now, victims of what is now called the Sixties Scoop are coming together–in love, fear and trepidation.

The Sixties Scoop is a catch-all name for a series of policies enacted by provincial child welfare authorities starting in the mid-1950s during which thousands of Indigenous children were taken from their homes and families.

The children were placed in foster homes and eventually adopted out to white families from across Canada and the United States, losing their names, their language, their mothers, fathers, sisters and brothers.

Many of those children–much, much older now–are now reuniting with their families.

One of those reunions took place Tuesday at Regina International Airport.

The brothers look on as some of Helliwell’s grandchildren stand in front of them. (Liam Avison/CBC)

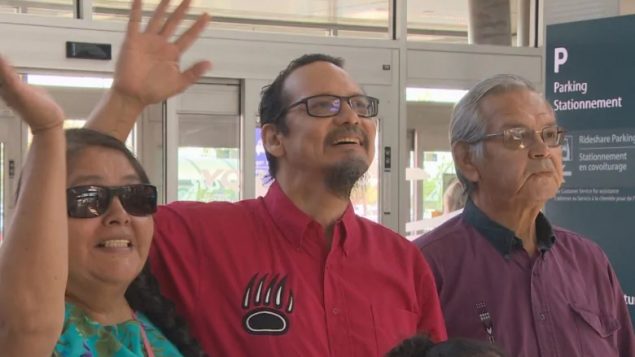

Nick Helliwell and his brother Anthony Stonechild saw each other for the first time in 50 years.

When they last embraced, Helliwell was two and Stonechild was four.

“I recognized him immediately as I saw him come down the walkway. I just knew it was him,” Helliwell told CBC News’ Emily Pasiuk.

“It’s like spirit. It’s still there,” Stonechild told Pasiuk.

Joining the embrace was their brother Henry Blair Pascal as well has Helliwell’s wife and grandchildren.

Another brother, who brought Helliwell and Stonechild together through Facebook, was home in Prince Alberta and will receive a visit later this week.

Both Stonechild and Helliwell were in multiple homes as children.

Stonechild remembers being moved every three months.

When Helliwell, centre, saw his brother on the walkway, ‘I just knew it was him.’ (Liam Avison/CBC)

“I call it the kaleidoscope of life. Every three months I would close my eyes, open them and everything is different.”

Helliwell lived in 15 different homes before he was six.

The unending upheavals left marks they still must salve.

“That experience completely disconnected me from my sense of family or home,” Helliwell told Pasiuk.

“Reconnecting with family now becomes a really, really scary prospect for me because I realize that very fundamental parts of my being have been damaged.”

Stonechild, who lives in Vancouver, says he has lived a lonely life, suffering from what he says were shame and prejudices imposed because he was Indigenous.

He says people reached out to him but he did not know who to respond.

“This is the first time I’ve walked into a world that I really feel I belong back in.”

The brothers have family in the Peepeekisis First Nation, 90 miles north of Regina.

They plan to travel there this week, together.

With files from CBC

For reasons beyond our control, and for an undetermined period of time, our comment section is now closed. However, our social networks remain open to your contributions.