As provincial governments across Canada prepare plans to gradually lift lockdowns and reopen parts of the economy shuttered by the global pandemic, experts warn that policy-makers have no room for error in this unprecedented public health experiment.

But that seems to be pretty much the extent of the consensus in the expert community on how to go about lifting the lockdowns and reopening the economy without triggering another wave of infections that would overwhelm Canada’s already strained health system.

While some, like Dr. Christopher Mody, advocate for measures to quickly build up herd immunity by allowing carefully selected segments of the population to mix and thus get exposed to the coronavirus, others, like Dr. David Buckeridge, warn against going too fast and relying too much on the concept of herd immunity to guide policy making.

For Mody, who heads the Department of Microbiology, Immunology and Infectious Diseases at the Cumming School of Medicine, at the University of Calgary, it comes to a careful balancing act between protecting the most vulnerable segments of the population and “lifting up the lead” on lockdown measures for less vulnerable segments of the population, such as post-secondary students and younger adults.

We’ve flattened the curve, now what?

Police cadets keep an eye on social distancing in Lafontaine Park Friday Apr. 3, 2020 in Montreal. (Ryan Remiorz/THE CANADIAN PRESS)

While public health measures such as physical distancing and lockdowns have been very successful in flattening the curve and preventing the peak of the pandemic from overwhelming Canada’s health care system, these measures have also extended the length of the pandemic, Mody says.

“When we talk about flattening the curve what we mean by that is reducing the height of the peak,” Mody says.

“What was important during the initial part of the pandemic, it was pretty clear that if we left this thing run all by itself without doing something, the peak was going to exceed our capacity to deal with cases with the current healthcare system.”

And so Canadians pitched in and by staying at home and following other public health measures, they managed to reduce that peak, he says.

“But when you do those things, what you do is you actually push cases into the future. You don’t actually reduce the total number of cases,” Mody says.

“You flatten and widen the curve. The consequence of that is that if we let that happen, we’re going to see a smaller number of cases at the peak, that’s great, but we’re still going to have cases through May, June, July, August, maybe even into the fall, because we basically extended that tail out that far. We’ve done such a good job pushing down the peak that we extended it out the other side.”

That’s not what we want, he says.

“What we want to do, we want to be smart about this,” Mody says. “What we want to do is to actually reduce the number of cases while simultaneously accomplishing a number of other goals.”

The first goal is to reduce the number of cases and that means decreasing the area under the curve, Mody says.

“Simultaneously we want to protect people that are going to get really sick and potentially die of COVID-19,” he says. “Simultaneously we want to restart an economy, we want to restore people’s lives and family units and social proximity, as well as physical proximity, we want all those things to happen.”

A chink in COVID-19’s armour?

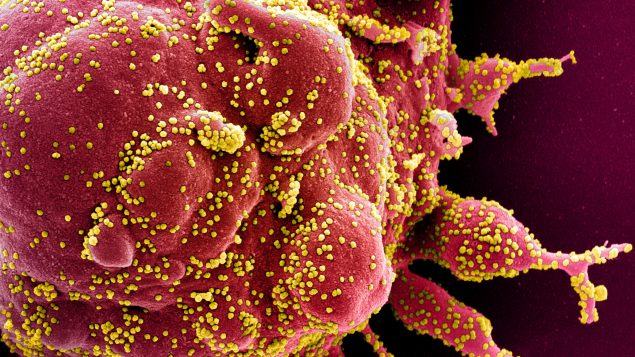

An undated transmission electron micrograph of a SARS-CoV-2 virus particle, also known as novel coronavirus, the virus which causes COVID-19, isolated from a patient. (NIAID Integrated Research Facility (IRF)/Handout via REUTERS.)

And COVID-19 has a “chink in the armour” that we might be able to exploit, Mody says.

Unlike the 1918 pandemic that killed people who were young, which made it difficult to protect the vulnerable population and restore an economy, COVID-19 kills mostly older adults while younger people are relatively protected, he says.

“So basically, we have an opportunity, we have an opening, we have the possibility of introducing it in such a way that we can introduce it to a segment of the population, while still trying to protect another segment of the population,” Mody says.

“Now, that’s going to take very strategic loosening of restrictions, lifting the lead if you will. Because you’ve got to lift the lead in a way that still protects elderly patients.”

Since there is no vaccine and we’re not going to have a vaccine in the near future, if ever, we have to resort to the way humanity has fought pandemics since time immemorial, says Mody.

“Everybody didn’t get infected and everybody didn’t die because humans as a population developed immunity,” Mody says.

“If enough humans get infected and survive and develop immunity, then one infected patient doesn’t contact another susceptible individual because all the people who are in between those two people are immune and the virus can’t transfer through an immune person.”

Start working on herd immunity

That’s basically the idea behind the concept of herd immunity, he says.

“We want to develop herd immunity in the population,” Mody says.

The idea is to develop herd immunity in the population by exposing people who will get infected and will have a much smaller chance of an adverse outcome, and protect those people that cannot deal with the infection or are much more likely to have an adverse outcome.

That has to be done really strategically, Mody says.

“We need to specifically target segments of the population where we bring them back into contact in a way that actually promotes herd immunity and that we actually follow that herd immunity to see whether we’re successful or not,” Mody says.

That would require a lot of antibody testing to track the epidemic, he says.

And it’s not without risks.

“When we start reducing restrictions, people are going to get sick, people are going to go to hospital, and even young people are going to die. And we have to understand that,” Mody says.

“This is not a perfect strategy. But by doing this strategy a lot less people will suffer, a lot less people will go to hospital and fewer people will die.”

People under the age of 40 could be one of the first groups to have restrictions carefully lifted and resume normal activities, Mody says.

“But we need to protect the vulnerable populations, we need to protect people that are in contact with elderly people,” says Mody. “So if a public school student is looked after by their 75-year-old grandmother and grandfather, it’s a bad idea, really bad idea.”

Sectors of the population that have young people in them – post-secondary students, trades people – could also be possible candidates for selective lifting of restrictions because they are going to be in less contact with vulnerable populations, Mody says.

“It requires some analysis of what’s the demographic in there and how often are they going to contact vulnerable populations and during this time can we actually increase protections for the vulnerable populations,” says Mody.

“The issue is not to lift the lead for everybody but to lift the lead for those who can handle it while simultaneously protecting the people that can’t.”

A demographic challenge

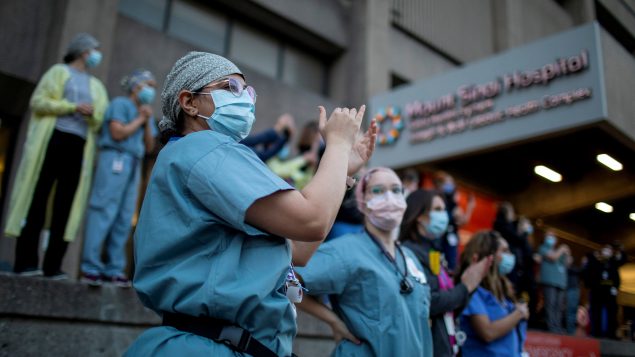

Healthcare workers clap as Toronto Police and the city’s front-line responders pay tribute to healthcare workers along University Avenue as the number of coronavirus disease (COVID-19) cases continue to grow in Toronto, Ontario, Canada Apr. 19, 2020. (Carlos Osorio/REUTERS)

However, Canada’s demographic makeup could interfere with the strategy of building herd immunity.

According to Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health epidemiologists Gypsyamber D’Souza and David Dowdy, we will likely need at least 70 per cent of the population to be immune to have herd protection against SARS-CoV-2, the virus that causes COVID-19.

That would mean 26.6 million Canadians would have to have immunity against SARS-CoV-2, for herd immunity to work.

That basically means that every Canadian below the age of 55 would need to be either exposed to the virus or get vaccinated at some point in the future for herd immunity to work.

McGill University epidemiologist David Buckeridge says the herd immunity debate misses the point.

“It’s a great goal, the question is how you get there and how you get there in a way that you’re reasonably sure that you’re not going to have unexpected consequences,” says Buckeridge.

“I think the really big message in terms of anything we do, whether we’re thinking herd immunity or not, is do we have the systems in place to do sufficient amount of testing and make sure that data from testing gets back into the system quickly so that we know if we have gone too far before it’s too late.”

The problem with epidemics is exponential growth and it could be very challenging to stop that spread if we don’t have the capacity to track infection rates relatively quickly, says Buckeridge.

“To open up society we have to be thinking about who’s going to be infected and how that transmission is going to spread through the population and at what rate, whether we’re thinking about it from the herd immunity perspective or not,” says Buckeridge.

“My point is: it’s more important to think about the process we’re going to use to open up the population and understand how quickly infection is spreading through any subpopulation, whether it’s kids or anybody else, so that we can control the rate of that spread no matter how we go about it.”

That’s the most critical piece because it’s going to take us time to get to that number of infections, he says.

“Although we all want to get out of this faster, the last thing we want is to have uncontrolled spread in the population, in any population because then we have no way of slowing things down,” Mody says.

Canada’s Chief Public Health Officer Theresa Tam is also urging people to be “extremely cautious” about the concept.

“The idea of … generating natural immunity is actually not something that should be undertaken,” Tam said Saturday.

For reasons beyond our control, and for an undetermined period of time, our comment section is now closed. However, our social networks remain open to your contributions.