Blog: The Maine doorway to the Arctic

A few weeks ago, I took a red-eye flight from Los Angeles to the Arctic. Or at least that’s how some officials in Maine might describe my destination, which was the coastal of Portland, population 66,000.

That’s because Maine is increasingly looking northeast for political and economic support rather than southwest to the rest of the United States. This new direction in outlook largely draws inspiration from Icelandic shipping company Eimskip’s relocation in 2013 of its North American port of call from Norfolk, Virginia over 1,000 kilometers up the Atlantic seaboard to Portland, Maine’s largest city.

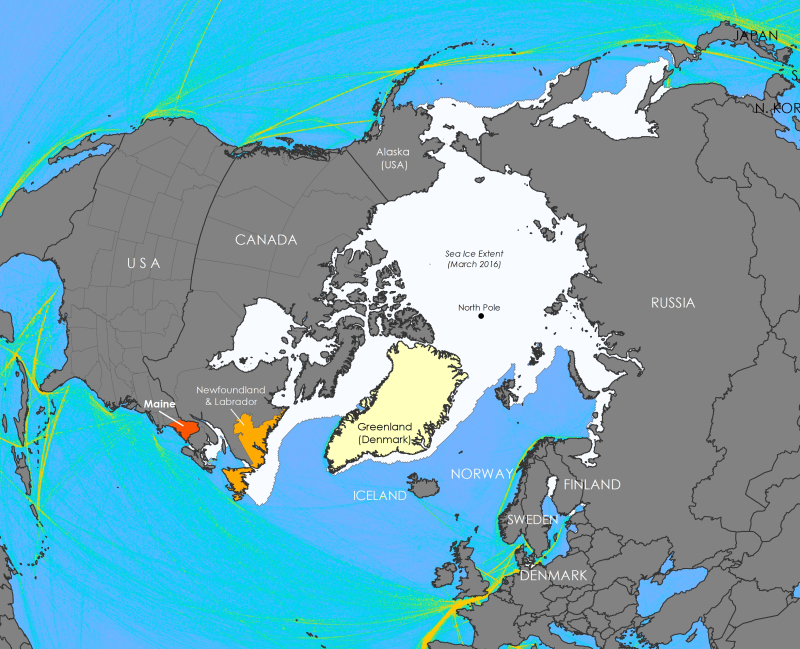

Yet Maine’s connection to the Arctic is a lot more than three years old. My reason for traveling to the United States’ northeasternmost state was to give a talk at Bowdoin, a picturesque liberal arts college thirty minutes north of Portland in the town of Brunswick. For over 150 years, Bowdoin has held a connection to the Arctic through its students and professors. In 1860, a professor from Bowdoin led a group of students to Labrador and West Greenland – two areas that are just a hop, skip, and jump between Maine and the North Pole, as depicted by the above map. Bringing the glory of Arctic exploration at the time to Maine, between the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, two Bowdoin graduates, Robert Peary and Donald MacMillan, led numerous expeditions to the Arctic both together and separately. In 1909, Peary and his team, including four Inuit men and African-American Matthew Henson, claimed to be the first to reach the North Pole after originally setting off from New York City the summer before.

Yet Maine’s connection to the Arctic is a lot more than three years old. My reason for traveling to the United States’ northeasternmost state was to give a talk at Bowdoin, a picturesque liberal arts college thirty minutes north of Portland in the town of Brunswick. For over 150 years, Bowdoin has held a connection to the Arctic through its students and professors. In 1860, a professor from Bowdoin led a group of students to Labrador and West Greenland – two areas that are just a hop, skip, and jump between Maine and the North Pole, as depicted by the above map. Bringing the glory of Arctic exploration at the time to Maine, between the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries, two Bowdoin graduates, Robert Peary and Donald MacMillan, led numerous expeditions to the Arctic both together and separately. In 1909, Peary and his team, including four Inuit men and African-American Matthew Henson, claimed to be the first to reach the North Pole after originally setting off from New York City the summer before.

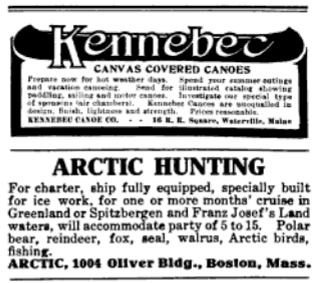

While Peary’s claim has been disputed for over one hundred years (the first incontrovertible conquest of the North Pole did not occur until 1928, when Norwegian explorer Roald Amundsen flew over it in an airship), he, MacMillan, and their supporters established a tradition of Mainers in the Arctic that is today being revived academically, economically, and politically. For instance, Maine’s Senator Angus King is a founding co-chair of the U.S. Senate’s Arctic Caucus along with Senator Lisa Murkowski from Alaska. Maine’s North Atlantic Development Office, referred to as MENADO, was formed in 2013 to enhance trade and investment between Maine and the North Atlantic region and to build the state’s Arctic policy. These efforts also connect with New England’s historic connection to the Arctic’s resources, like during the nineteenth century when Arctic whaling expeditions would set out from New Bedford, Massachusetts – the former whaling capital of the world. And in a 1912 issue of hunting and fishing magazine Forest and Stream, an ad for an Arctic hunting vessel for charter out of Boston appeared under an ad for canoes from Waterville, Maine.

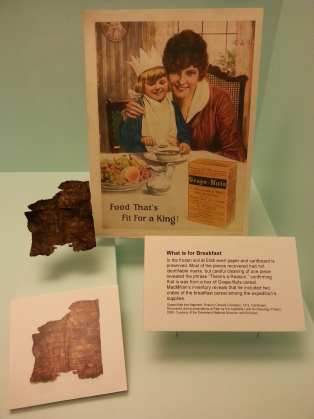

Bowdoin’s Peary-MacMillan Arctic Museum, one of two Arctic-only museums in the United States, celebrates the accomplishments of the two eponymous individuals and others, such as Henson, who is often left out of historical accounts of Arctic exploration. One current exhibit, “A Glimmer on the Polar Sea: The Crocker Land Expedition, 1913-1917,” discusses MacMillan’s effort to try to find a fabled landmass north of Alaska in the Arctic Ocean, which ultimately proved to be a mirage. A Bowdoin team leading an archaeological dig in Etah, Greenland, an abandoned settlement that once was a starting point for expeditions northward, revealed an empty package of Grape-Nuts that MacMillan had brought for the Crocker Land Expedition. Grape-Nuts, as I learned, have traditionally been popular in Maine and New England, with some restaurants even serving “Grape-Nut pudding.” Post Grape-Nuts was so excited about the discovery of Grape-Nuts, which are probably rarer than gold nuggets in the Arctic, that they sponsored the reception for the exhibit. Not to miss a marketing opportunity, they insisted that two dishes made out of Grape-Nuts be served.

Given its hardiness, crunchiness, and caloric density, this New England staple could be considered a food fit for Arctic explorers in line with pemmican and walrus blubber. In fact, Grape-Nuts have also fueled expeditions to Antarctica and Mt. Everest and America’s World War II operations in the tropics. Since I would bet that nobody in the history of mankind has ever eaten Grape-Nuts without spilling a few of these miniscule crunchy nuggets around them, I can only imagine future archaeologists looking for remnants of this breakfast cereal (which also never seems to go stale) in the Arctic and beyond.

After my visit to Bowdoin, I traveled back down to Portland. There, I toured Eimskip’s port facilities, met with a professor from the University of Southern Maine working on Arctic law of the sea issues, and visited the offices of Ramboll – the world’s leading consultancy in the Arctic. Portland, a hip town with a working waterfront and supposedly the most restaurants per capita in the United States, also might have perhaps the most Arctic-engaged people per capita in the nation outside of Alaska.

This fall, since the U.S. is currently chair of the Arctic Council, Portland will host numerous Arctic events building off of the Arctic Council’s Senior Arctic Official meeting, which will take place from October 4-6. With the Arctic Circle conference – “the world’s largest global assembly on the Arctic” – starting the day afterwards in Reykjavik, participants will be able to easily catch the five-hour direct flight from Boston’s Airport, less than two hours away from Portland, to Iceland.

This ease of connection between Maine and northern places like Labrador, Greenland, and Iceland underscores Maine’s relative proximity to the Arctic, even if its actual inclusion within the region is up for debate. Folks in Alaska are grumbling about having to fly all the way to Maine for the Arctic Council events. In reality, Alaska is more isolated than Maine in relation to where a lot of the current Arctic development is happening: in the North Atlantic rather than the North Pacific. For all of the Canadians, Europeans, and Russians based in their nation’s capitals and centers of power who have to travel to the U.S. this year for Arctic Council meetings, Maine is closer than Alaska. It’s more or less business as usual, then, with the future of the Arctic being decided in the south.

In my next post, I’ll write more about Eimskip’s operations in Portland, Maine – a state which I heard one Icelander refer to as being like “Iceland that speaks English.”

This post first appeared on Cryopolitics, an Arctic News and Analysis blog.

Related stories from around the North:

Asia: Asia ahead on preparing for polar climate change, says U.S. Arctic rep, Eye on the Arctic

Canada: Blog: The return of the Arctic Five, Eye on the Arctic

China: China’s silk road plans could challenge Northern Sea Route, Blog by Mia Bennett

Finland: US seeks Finnish support for Arctic goals, Yle News

Greenland: Arctic countries ban fishing around North Pole, Alaska Dispatch News

Norway: China eyes Arctic Norway infrastructure projects, Barents Observer

Russia: The Arctic Council’s Immunity to Crimean Flu, Blog by Heather Exner-Pirot

Sweden: Arctic Council – From looking out to looking in, Blog by Mia Bennett, Cryopolitics

United States: Arctic Alaska meeting planned for Kerry, Lavrov and other officials, Alaska Dispatch News