Canadian eastern Arctic: Inuit organization accuses Nunavut’s education system of ‘cultural genocide’

An Inuit organization in charge of overseeing the implementation of the Nunavut Agreement that created Canada’s newest Arctic territory 20 years ago told a United Nations meeting Monday that both the federal and territorial governments are complicit in “cultural genocide” for failing to protect the Inuktitut language.

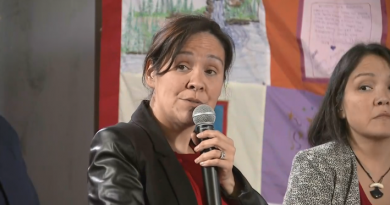

During a three-minute presentation at the 18th session of the UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues, Nunavut Tunngavik Incorporated (NTI) president Aluki Kotierk said both levels government have failed so far to deliver on their promise to protect and promote the use of Inuktitut.

Speaking with Radio Canada International from New York City, Kotierk said during her presentation she referenced a report commissioned by NTI and titled “Is Nunavut education criminally inadequate? An analysis of current policies for Inuktitut and English in education, international and national law, linguistic and cultural genocide and crimes against humanity.”

The report, which was written by Rob Dunbar, a professor at the University of Edinburgh, Tove Skutnabb-Kangas, a Finnish linguist and educator, and Robert Phillipson, a professor at the Copenhagen Business School, analyses domestic and international legislation in terms of Indigenous language rights, she said.

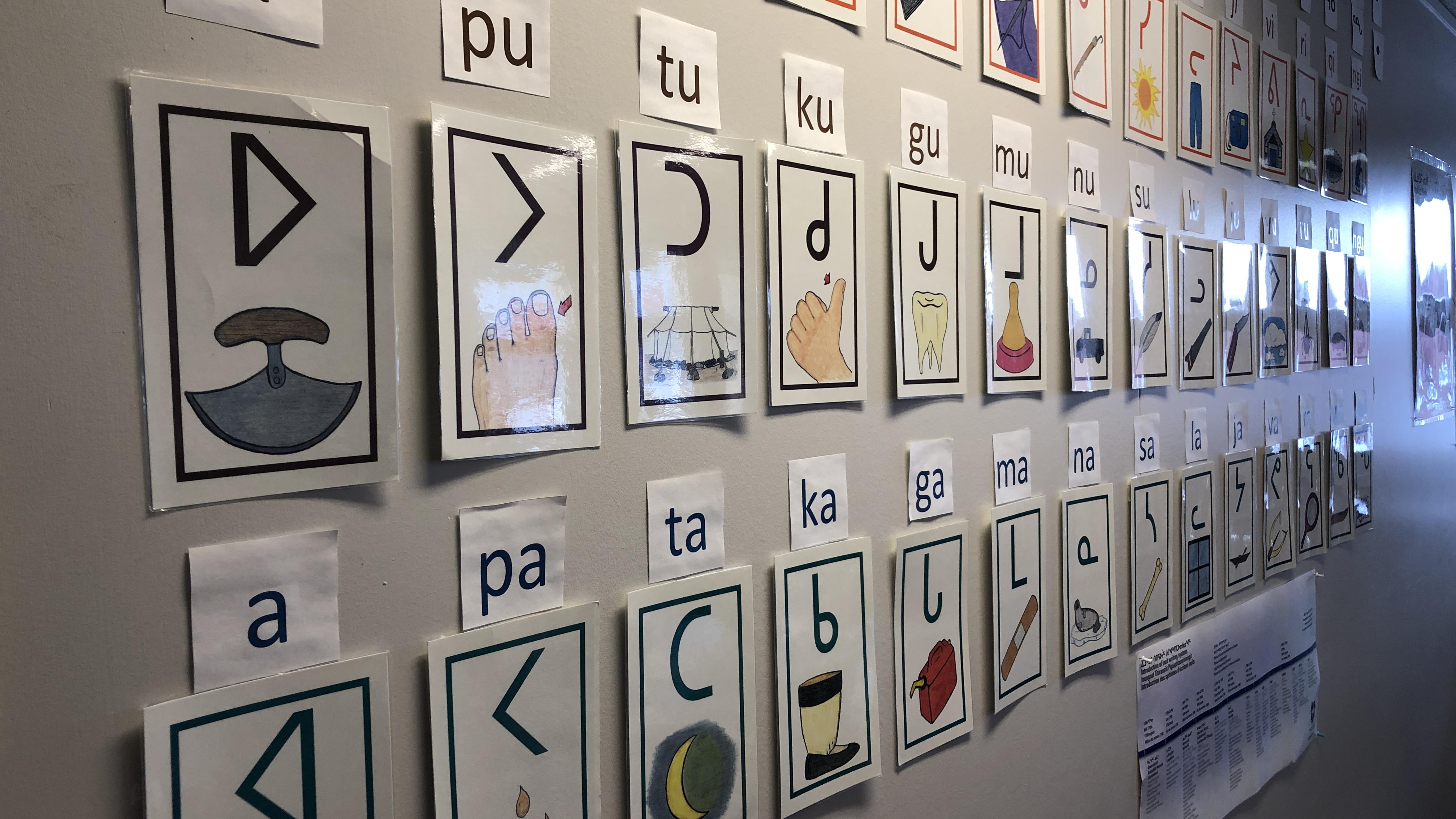

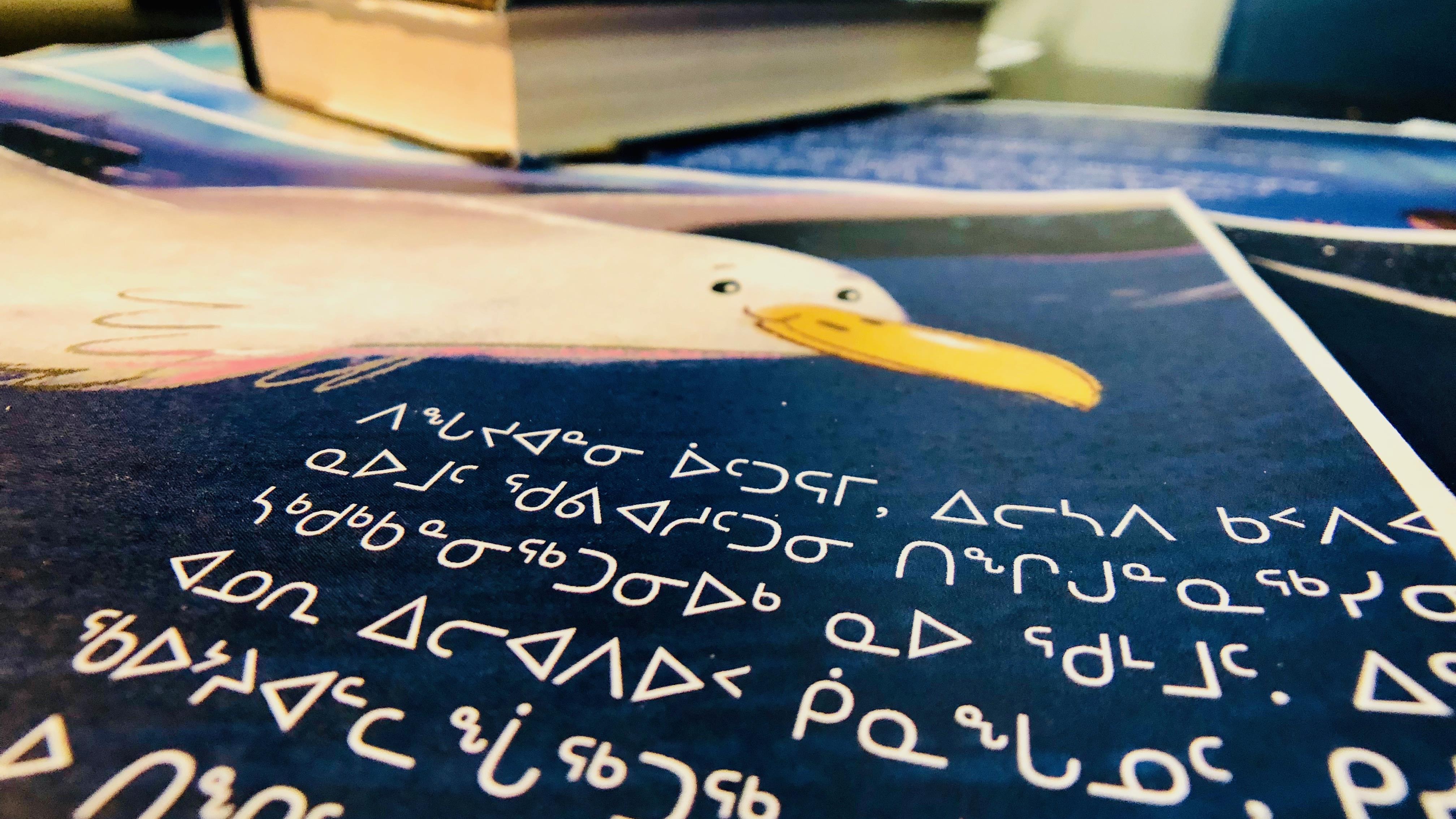

It specifically looks at Nunavut, where despite the fact that Inuktitut is the language of the majority Inuit population of the territory, the school system is mostly in English, Kotierk said.

‘A crime against humanity’

“When a child is not being taught in their mother tongue, it could potentially be a crime against humanity,” Kotierk said.

(Click to listen to the full interview with Aluki Kotierk)

Education in Nunavut has a history of cultural genocide, destruction of Inuit language and history that continues to this day, she added.

“We have language rights, we expect to be able to receive essential services and programs in Inuktitut,” Kotierk said.

But Inuktitut is not provided nearly the same level of resources and support as French or English-speaking minorities receive in other parts of the country, she said.

“One of the things that I would hope this report does is create the space to have dialogue about the resources that are required as well as the ideological change or approach that needs to take place,” Kotierk said. “As Inuit parents we want our children to go to school in Inuktitut.”

The report speaks to the benefits of having education in the students’ mother tongue, she added.

“What we would like to see is that there be a robust and concerted effort to increase the number of Inuktitut-speaking teachers,” Kotierk said.

But that alone won’t be enough, she said.

Additional resources need to be allocated to ensure that an Inuit-centred curriculum is developed, and teaching materials and resources are developed to allow teachers to teach in Inuktitut from kindergarten to Grade 12, Kotierk said.

“In addition to that, I think there needs to be a change in the way in which the government functions in Nunavut,” Kotierk said.

Pressure to assimilate

Karla Jessen Williamson, assistant professor at the University of Saskatchewan who specializes in Inuktitut education, said the education system in Nunavut is a “travesty.”

Nunavut has nothing to celebrate when it comes to its Inuktitut education system, she said.

“The achievement so far has been really-really dismal in terms of keeping up the language of the Inuit,” Jessen Williamson said.

Some studies suggest that the use of Inuktitut has declined by 10 per cent in the last 20 years, Jessen Williamson said.

“For those of us that are in the Indigenous communities the incredible pressure to become assimilated into these languages [English or French] is incredibly strong,” Jessen Williamson said. “And the way in which Inuktitut has been disappearing has been very-very profound.”

Investing in Indigenous languages

Nunavut Premier Joe Savikataaq dismissed the report as “somewhat one-sided and based on the research of academics from outside our territory.”

“I appreciate and respect NTI’s passion for education and language preservation, and I continue to encourage them to work directly with us to find solutions together to our shared goals to revitalize Inuktut in Nunavut,” Savikataaq said in an emailed statement to Radio Canada International, referring to a term that describes both Inuktitut and Inuinnaqtun, the two official Indigenous languages of Nunavut, and their various dialects.

Simon Ross, press secretary of Minister of Canadian Heritage and Multiculturalism Pablo Rodriguez, said the Liberal government of Prime Minister Justin Trudeau is very cognizant of the fact that Indigenous languages across the country are endangered and disappearing.

“This is a direct consequence of the government’s past actions meant to destroy Indigenous cultures,” Ross said in an emailed statement. “We are taking action and making history.”

The Liberal government has tabled Canada’s first bill on Indigenous Languages and has invested $334 million to strengthen and revitalize Indigenous languages, he said.

“This investment is an important first step,” Ross said. “This is Reconciliation in Action.”

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: U.N. Year of Indigenous Languages: When policy isn’t enough, Eye on the Arctic

Finland: Budget cuts threaten international Sámi language cooperation, Yle News

Iceland: Can environmental diplomacy save Arctic languages?, Blog by Takeshi Kaji

Norway: Inuit, Sami leading the way in Indigenous self-determination, study says, CBC News

Russia: Sami languages disappear, The Independent Barents Observer

United States: Alaskan Inuit dialect added to Facebook’s Translate app, CBC News