Meteorologists should watch the tropics rather than the Arctic to predict extreme cold in North America, study says

Meteorologists often look at the behaviour of the polar vortex to predict extreme cold events in North America, but the real key may lie further south, according to a new study.

“Despite the most extreme cold snaps experienced in North America often being described as ‘polar vortex outbreaks’, our study suggests vortex strength should not be considered as a cause,” researcher Simon Lee, an atmospheric scientist at the University of Reading in England, said in a news release.

The stratospheric polar vortex is a river of winds that circles the Arctic at heights of 10–50 km, trapping cold air inside.

In Europe and Asia, it is the strength of these winds that creates the episodes of cold winter. When the polar vortex weakens, it releases cold, freezing air from the Arctic to southern regions.

“We know that a weakened polar vortex allows cold air to flood out from the Arctic over Europe and Asia, but we found this is surprisingly not the case the other side of the Atlantic,” Lee said.

“In fact, our work suggests we should actually look south to conditions around the equator, rather than north to the Arctic, for the causes of these widespread freezing conditions in North America.”

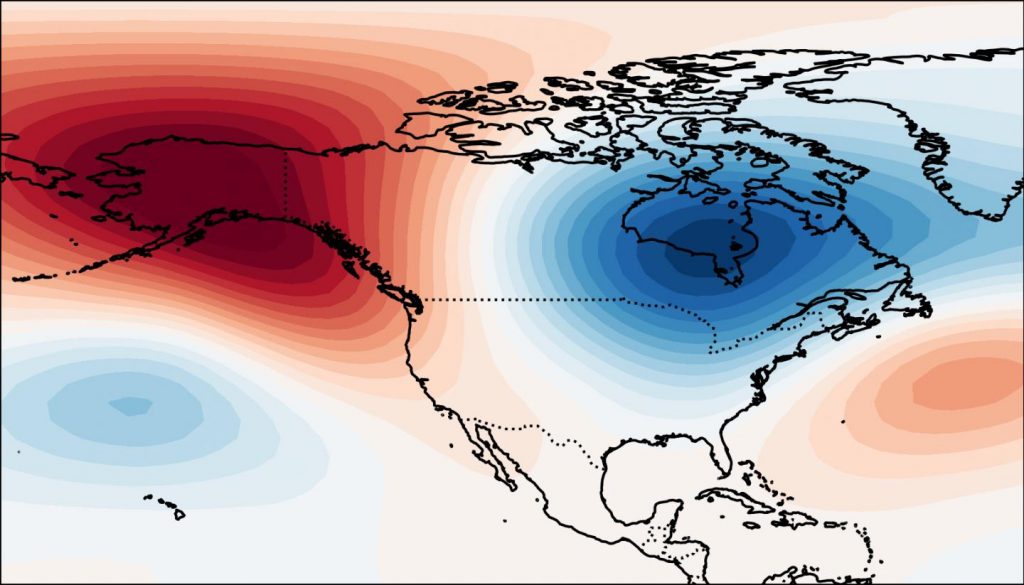

The study found that when tropical atmospheric patterns at the equator push high-pressure systems northward to Alaska, they cause the polar vortex and its freezing winds to move towards southern parts of North America.

So, extreme cold episodes are not due to the weakening of the polar vortex as in Europe or Asia, but rather to its move southward in the lower atmosphere.

This phenomenon affects the Alaskan Ridge regime which is associated with the most extreme and widespread cold in North America.

Useful for weather forecasting in North America

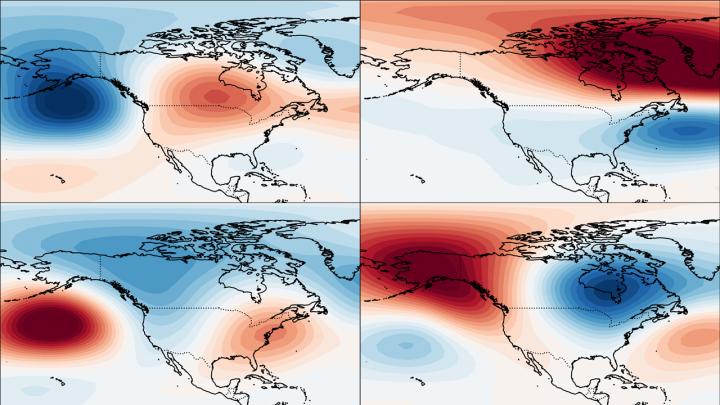

Apart from the Alaskan Ridge regime, scientists also looked at the three other winter weather patterns affecting the North American continent—Pacific Trough, Arctic High and Arctic Low.

They found that the strength of the polar vortex has a real influence on them. By looking at the polar vortex, meteorologists could potentially better predict severe weather moving across the continent, for example.

“Our results did reveal that the polar vortex strength provides useful information on the likelihood of most weather patterns over the US and Canada further in advance, including some potentially disruptive temperature changes or heavy rain.” Lee explained.

As an example, a strong polar vortex increased the likelihood of extremely cold conditions in the western parts of North America—including Alaska—by up to 11 percent.

On the opposite, it also suggests much milder conditions in the central and eastern parts of the US.

Now, the authors hope their work will inspire scientists to incorporate the polar vortex into their winter weather forecasting models, but also tropical atmospheric models such as El Niño.

The study has been published in the journal Geophysical Research Letters.

Related stories from around the North:

Antarctica: Could snow cannons in Antarctica help avert catastrophic sea level rise?, Eye on the Arctic

Canada: Bizarre winter weather in South caused by changes in atmosphere, not sea-ice loss: study, CBC News

Finland: Cooler summer weather has positive effects in Finland, Yle News

Greenland: Evidence of powerful solar storm which occurred 2,600 years ago found in Greenland ice, CBC News

Norway: Arctic summer 2019: record heat, dramatic ice loss and raging wildfires, The Independent Barents Observer

Russia: A hot summer across the Arctic, Russian meteorological institute says, The Independent Barents Observer