Inuit org says term “local communities” undermines Indigenous rights on international stage

The Inuit Circumpolar Council (ICC) says the use of the term “local communities” by UN member states, as well international forums, undermines Indigenous rights and should be replaced.

“The undermining of the rights of Inuit and other Indigenous peoples by States and intergovernmental organizations is unacceptable, particularly at a time of surging international interest and activity throughout Inuit Nunaat now unfolding against the backdrop of a global climate crisis and pandemic,” said ICC Chair Dalee Sambo Dorough in a news release.

Inuit Nunaat refers to the traditional Inuit homeland that spans Alaska, northern Canada, Greenland, and Chukotka, Russia. ICC represents the approximately 180,000 Inuit in the region.

“The grouping of Indigenous peoples with “local communities” in conventions and multilateral agreements has resulted in the slow and incremental erosion of the distinct nature of the interrelated, interdependent and indivisible rights of Indigenous peoples,” she said.

“Alarming trend”

In a policy paper released on Monday, ICC says the term suggests that Inuit rights are on par with local Arctic communities, without taking into account the internationally recognized rights of Indigenous peoples.

“Although State and intergovernmental organization motives for grouping and conflating Indigenous peoples with local communities is unclear, doing so diminishes the distinct rights and status of Inuit and other Indigenous peoples and may undermine the full and effective participation of Inuit in intergovernmental organizations and fora,” the policy paper said.

“This trend is alarming due to the uncertain legal status of local communities as well as the unclear meaning of this term. Language advanced by States and intergovernmental organizations has tended to suggest a false equivalency of rights between Indigenous peoples and local communities, potentially undermining advances made by Inuit and other Indigenous peoples to secure recognition of our distinct status, rights, jurisdiction, and roles vis-à-vis all others.”

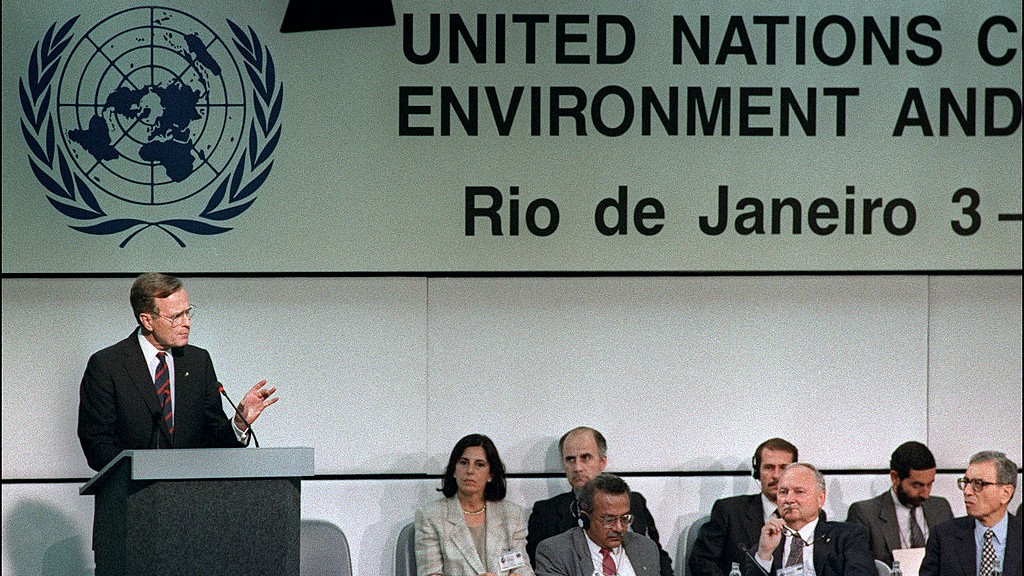

The ICC says the term first appeared in the context of international environmental law during the UN Conference on Environment and Development in 1992 in Rio de Janeiro.

“The element of grassroots participation is central to environmental law, often resulting in the pitting of Indigenous peoples’ rights and claims to land and decision-making in favor of “local” groups including farmers, environmentalists, etc.,” the policy paper says.

“Similar to other attempts to lump Indigenous peoples into other collective terms is problematic because the term “local” does not account for Indigenous peoples who have been removed from their lands and discounts the particular circumstances of Inuit. Among numerous examples, the creation of major national parks in Alaska without accommodating Inuit use, occupancy, status, rights, and role is a dramatic one in the context of millions of acres of land.”

Inuit are rights holders, not stakeholders says ICC

The ICC says reference to “local communities” or “local knowledge” has gained a foothold since appearing in related documents from the Rio conference right up to language used in the Paris climate agreement and the 2018 Agreement to Prevent Unregulated High Seas Fisheries in the Central Arctic Ocean.

Something the organization says sends a message that local inhabitants of a particular Arctic community have the same internationally protected rights as Indigenous people do.

“States have recognized the distinct rights and status of Inuit in domestic law and policy, including through constitutional recognition of Inuit rights, national and sub-national legislation, and Inuit land claims agreements,” the policy document says.

“Local communities by contrast are neither a recognized minority population nor stakeholder group in the jurisdictions where Inuit live. And, the grouping of Indigenous peoples with local communities remains incongruous with the extensive domestic or national law, policy, and jurisprudence on the distinct status, rights, and role of Inuit [and other Indigenous peoples].

“The collective nature of Indigenous peoples’ human rights is among the fundamental differences between Indigenous peoples and various other stakeholders that are already represented by States. Grouping Indigenous peoples and local communities therefore likely provides a platform to a constituency that is already represented by States.”

The ICC policy paper makes five recommendations for change:

- recognition that Inuit are rights holders, not “stakeholders” or “minorities”

- that the UN and other international organizations reform procedural rules so Inuit and other Indigenous peoples have full participation

- that states and intergovernmental organizations implement distinctions-based policies and engage with Inuit as separate from civil society stakeholders

- the use of distinctions-based language by states and intergovernmental organizations co-developed with Inuit and Indigenous peoples

- discontinuation of drawing from language in documents prior to the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples (UNDRIP)

“Inuit are rights holders and we seek full and effective participation in all conventions, multilateral agreements, and international fora where our rights, culture, and way of life are impacted,” the ICC says.

“This can only be achieved if States and intergovernmental organizations cease grouping and conflating Indigenous peoples with “local communities”, reform outdated procedural rules that marginalize Inuit and other Indigenous peoples, and utilize the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples as a framework for uplifting the status, rights and participation of Indigenous peoples.”

Write to Eilís Quinn at eilis.quinn(at)cbc.ca

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: Reconciliation means doing business differently in Canada, northerners say, Eye on the Arctic

Finland: Miners hunting for metals to battery cars threaten Finland’s Sámi reindeer herders’ homeland, The Independent Barents Observer

Norway: The Arctic railway – Building a future or destroying a culture?, Eye on the Arctic

Russia: Russian Indigenous groups call on Elon Musk to boycott company behind Arctic environmental disasters, The Independent Barents Observer

Sweden: Sami in Sweden start work on structure of Truth and Reconciliation Commission, Eye on the Arctic

United States: Alaska reckons with missing data on murdered Indigenous women, Alaska Public Media