Low earthquake risk in Canada’s eastern Arctic, says paper

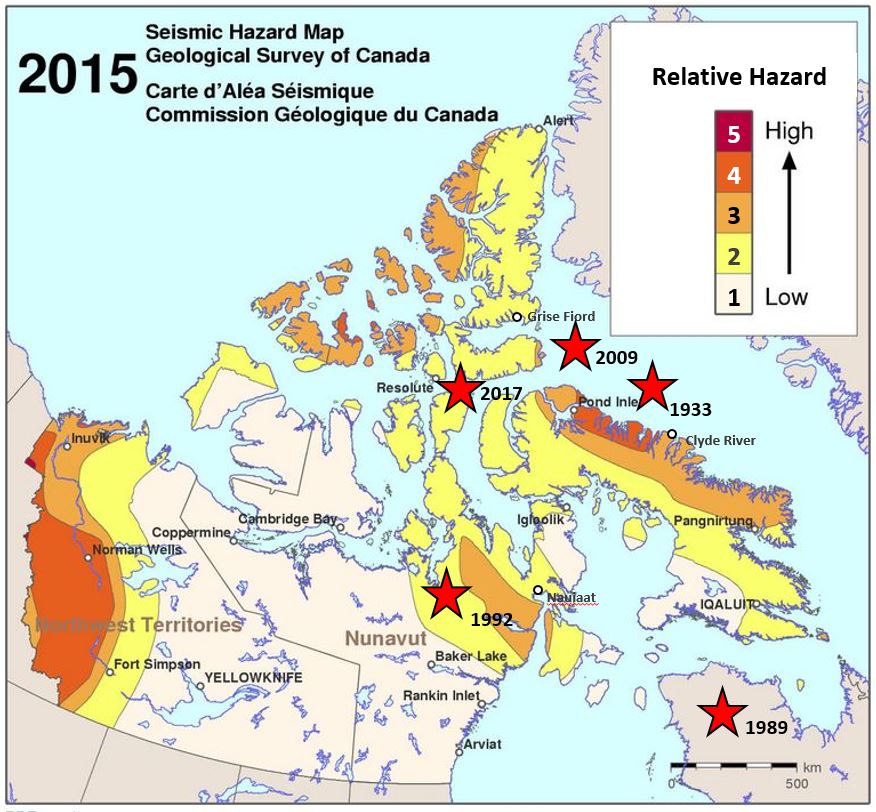

A paper exploring past, present and future earthquake risks in Arctic Canada shows dangers in the northeastern part of the country remain low.

The paper “Earthquakes in the Eastern Canadian Arctic: Past Occurrences, Present Hazard and Future Risk” was published in Seismological Research Letters by Natural Resources Canada research scientists Maurice Lamontagne and Alison Bent.

Unlike places that are on, or near, geographical fault lines or tectonic plate boundaries where the majority of earthquakes occur, Canada’s eastern Arctic is what’s known as a intraplate region where earthquake activity is low.

“Most earthquakes on a global scale occur at plate boundaries,” Lamontagne said in a telephone interview. “Plate boundaries are where tectonic plates move in respect to each other. So we can think of California, Japan, British Columbia and Alaska, but the eastern Arctic is not part of such a tectonic context.”

Ten significant earthquake events have been recorded in the region with magnitudes between 5.5 and 7.4, but only five of those events were noticed by people in local communities. None of them caused any damage.

The 1989 Ungava earthquake is the rare earthquake in the eastern Arctic that resulted in a visible fault line at the surface.

“When an earthquake occurs, it’s the friction on the fault that produces the seismic waves,” Lamontagne said.

“In general, this motion is deep inside the earth’s crust and in eastern Canada, generally it’s from 10 to 25 km under the surface. So when an earthquake occurs, we never see anything at the surface. We feel the vibrations but we don’t actually see movement on the fault.

“But we went to Ungava six months after the earthquake and we were able to see a rupture. So one side of a lake went down and the other side went up along the fault. And that was the first time something like that was seen in eastern North America.”

Climate impact on seismic activity in Canada’s eastern Arctic?

Climate change is unlikely to have any significant effect on seismic activity in the region, Lamontagne said.

“Climate change does not change the tectonic environment of earthquakes, or increase the likelihood they will occur” he said.

An exception could be in the cases of glaciers that decrease in size because of global warming.

“Very locally there is the potential to have small earthquakes because when you have a glacier sitting on the earth’s crust it’s more or less pushing down the crust,” Lamontagne said. “And when you remove this mass, sometimes the earth’s crust will tend to come back up and that can lead to earthquakes. But in the eastern Arctic, the masses of glaciers is so small we don’t think that it’s going to cause many earthquakes of interest.”

New infrastructure in the Arctic is already built with changing permafrost conditions in mind, however older buildings could be affected, as increasing thaw and freeze of the permafrost layer could make ground less stable and could result in increased damage to infrastructure should an earthquakes occur.

More ground movement could also potentially cause things like landslides, he said.

“In the paper, we say there are communities that could be affected by this potential for landslides in the future if we get a significant earthquake in the North, and this potential could be slightly greater than what we’ve seen in the past although probably more in the western Arctic than in the eastern Arctic.’

Write to Eilís at eilis.quinn@cbc.ca

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: What ancient earthquakes along the Denali fault in Yukon can tell us about what could come in Canada, CBC News

United States: No tsunami threat to B.C. after powerful M8.2 earthquake shakes Alaska, The Associated Press