The huge Greenland ice sheet is changing and in a newly discovered way.

Traditionally, snows falling on the ice sheet transform into new ice as they become compacted by the weight of several metres of snow falling on top of them year after year. This snow to ice layer is known in scientific circles as “firn”.

It was always thought that in periods of surface melting, the firn would act like a sponge and water would seep down through the porous snow with little “loss” to then freeze and remain as part of the ice sheet.

New research by an international team shows the firn reacting quickly and in a surprising way to climate change, and that ice-loss may be greater than thought.

Glaciologist William Colgan was a member of the research team. He is an assistant professor at York University’s Lassonde School of Engineering in Toronto Ontario.

Listen

The ice sheet itself is between 1.5 to 2 kilmetres thick at its deepest points, and normally the firn is up to 60 metres deep. What the researchers discovered was a previously unknown phenomenon which dramatically changes the firn and its composition.

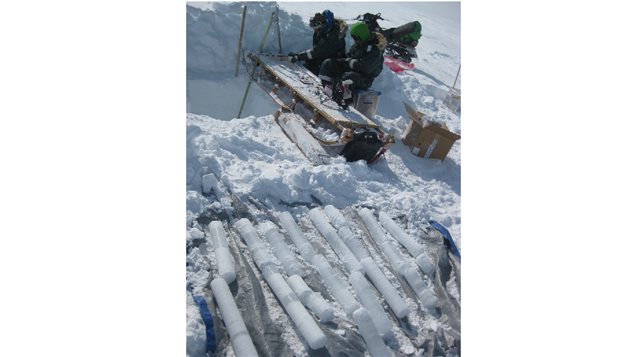

The research and analysis was performed in conjunction with lead researcher Horst Machguth of the Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland, Mike MacFerrin of the University of Colorado at Boulder and Dirk van As of the Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland. Three expededitions to the ice sheet were carried out in 2012, 2013 and 2015 to gather the data.

The study was published online January 4, 2016 in the scientific journal Nature-Climate Change

What they found was that an extreme melt in 2012 and subsequent freeze resulted in a thick layer of ice forming just below the surface. In subsequent melt periods the water which previously seeped down through many metres of porous snow, hit the solid ice cap. Instead of being re-absorbed by the ice sheet, it now flowed along the top of this ice-cap and into the sea as run-off in hundreds of rivers.

Colgan said the change was dramatic; “to see no rivers one year, and the next to see rivers extending ten or twenty kilometres inland and in places they had never been seen before”

Professor Colgan says, “It overturned the idea that firn can behave as a nearly bottomless sponge to absorb meltwater. Instead, we found that the meltwater storage capacity of the firn could be capped off relatively quickly.”

Colgan says the Greenland ice-sheet is losing an average of 8,000 tonnes of mass every second. What this new research shows is that the firn reacts quickly to climate change and is no longer necessarily the “bottomless sponge” that can reabsorb meltwater and limit overall mass loss.

As this is a new discovery, current modelling of the ice-sheet melt and its contribution to sea-level rise did not take this firn “cap-off” into consideration so that there may be more meltwater into the ocean than calculated. He estimates as high as a 30 percent increase in melt runoff or water loss over previous computer models which did not take this recent phenomenon into account.

Colgan says this same phenomenon is also likely occurring in several areas of glaciers and ice-sheets in the Canadian Arctic as well.

This new data will now have to be factored into computer modelling of melt and sea-level rise. Because this is a recent occurrence, he says until now ice-loss estimates are probably fairly accurate, but this will affect projected ice loss modelling.

Colgan says the change in the firn composition also affects the ice sheet “albedo” or sunlight reflection rate which in turn has an affect on melt rate. This will be his next area of research.

For reasons beyond our control, and for an undetermined period of time, our comment section is now closed. However, our social networks remain open to your contributions.