A report submitted to the UN Human Rights Council on Monday paints a bleak picture of anti-black racism in Canada.

Prepared by a UN working group that came to Canada last October, the report makes a series of recommendations to Canada’s federal government.

Those include apologizing for slavery and to consider making reparations for historical injustices.

(According to the 2006 Census by Statistics Canada, 783,795 Canadians identified as black, constituting 2.5% of the entire Canadian population. Of the black population, 11% identified as mixed-race of “white and black.”)

“History informs anti-black racism and racial stereotypes that are so deeply entrenched in institutions, policies and practices, that its institutional and systemic forms are either functionally normalized or rendered invisible,” the report says.

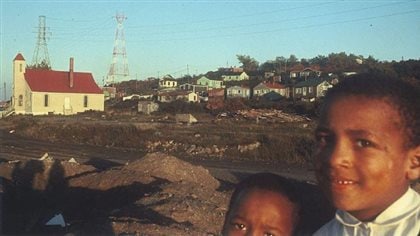

The report had especially harsh words for the situation in the East Coast province of Nova Scotia, calling current socio-economic conditions “deplorable,” and calling the displacement of black residents in Halifax’s Africville district in the 1960s a “dark period” in Nova Scotian history.

Urging the federal government to address the problem and citing statistics suggesting that black people are “extraordinarily overrepresented” when it comes to the use of lethal force by police, the report says Canada’s criminal justice system is marked by anti-black racism.

It notes that that between 2005 and 2015, the number of black inmates in federal prisons increased by more than 71 per cent.

Other recommendations include addressing what it calls “environmental racism,” the risks created by environmental hazards–landfills, waste dumps and pollutants that are disproportionally situated near black communities.

As well, the report recommends the creation of a federal department of African-Canadian affairs and providing compensation for the impacts of discrimination, such as targeted hiring practices similar to those for Indigenous Peoples.

For some perspective, I contacted Jack Jedwab, as expert on immigration, multiculturalism and human rights.

He is currently president of the Association for Canadian Studies (ACS) and the Canadian Institute for Identities and Migration and previously served as executive director of the Quebec branch of the Canadian Jewish Congress.

I spoke by phone with him at his Montreal office on Tuesday.

ListenWith files from Canadian Press, CBC, Postmedia

For reasons beyond our control, and for an undetermined period of time, our comment section is now closed. However, our social networks remain open to your contributions.