Concussion effects last longer than thought

A Canadian-Dutch collaboration into concussion research used a new technique to discover how the brain works around concussion damage.

The study, using functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) revealed interesting information about concussions and that brain changes lasted much longer than previously thought.

Ravi Menon (PhD) is a professor of medical biophysics at Western University’s Schulich School of Medicine & Dentistry, and scientist at Robarts Research Institute in London, Ontario and senior author of the study.

ListenGenerally, analysis of concussion effects have been subjective based on symptoms and recovery. The new technique provides a more objective analysis of the injury.

The study was published in the journal Neurolmage: Clinical, under the title, “Linked MRI signatures of the brain’s acute and persistent response to concussion in female varsity rugby players” (open access here)

Ravi Menon (PhD) Western University professor anddirector of the Western U. Centre for Functional and Metabolic Mapping. (Western University)

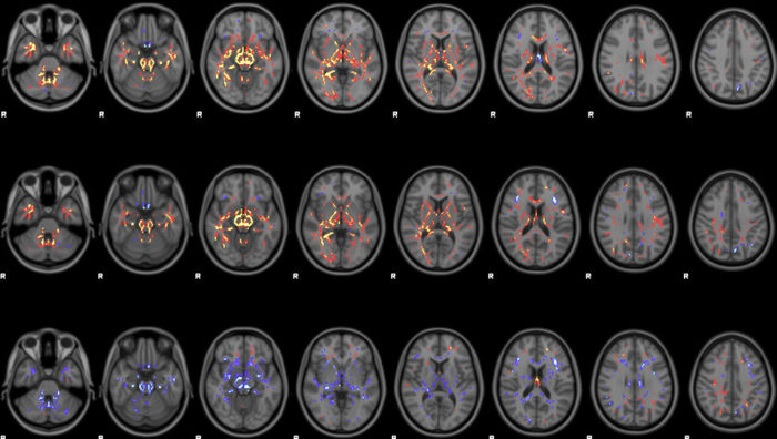

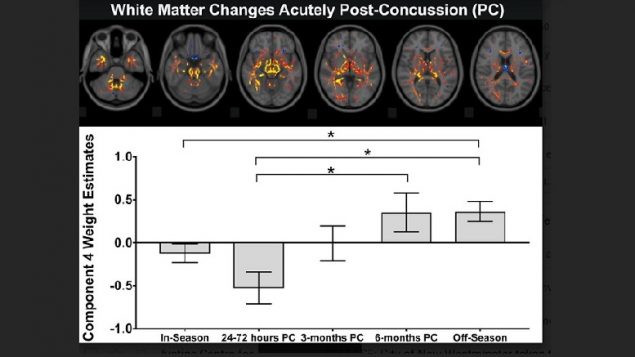

The innovative process combined simultaneous examination of both structural and functional information by combining multiple brain imaging measures.

The five-year study involved some 51 female university rugby players, 21 of whom had suffered a concussion.

What they discovered was the functional changes in the brain lasted long after any typical symptoms had cleared up.

What this means is that perhaps people playing sports should not be cleared to resume play simply once the symptoms of concussion are gone.

Professor Menon also says that their study showed three distinct injury signatures; one showing acute brain damage after a concussion, another showing changes that have persisted as long as six months later, and a third that shows evidence of concussion history.

The study looked at 51 female rugby players, about half of which had suffered a concussion. The research team used a technique that combined multiple brain imaging measures to be able to look at structural and functional information at the same time. The result was a much more sensitive and complete picture of concussion injury. ( Manning et al, Western U)

He also says the study showed that players who had not had concussion, still showed concussion like brain changes, possibly from repetitive low-level hits from “heading” the ball. Such changes were not evident in swimmers, a sport with virtually no incidence of concussive activity..

Menon says they don’t yet know why some people are able to sustain several concussions and function quite well, while others may exhibit long term problems after just one blow. He also suspects that each brain may have a finite limit to its “plasticity” that is the ability to develop new paths to “work around” a damaged area. The theory is that once the brain uses up all its alternative pathways, any future concussion could mean the brain has run out of options so-to-speak.

The 3-T MRI scanner used in the study is similar to technology widely available in medical centres so this newly developed technique can be easily used in other hospitals and clinics.

The study, in collaboration with the Donders Institute in the Netherlands, was funded by Schulich Medicine & Dentistry, Brain Canada, Western’s BrainsCAN, and NSERC

For reasons beyond our control, and for an undetermined period of time, our comment section is now closed. However, our social networks remain open to your contributions.