Growth in Arctic shipping warrants Polar Code adjustments, say experts

Despite dangerous and unpredictable conditions, Arctic shipping has seen seven per cent annual growth over the last decade, something that warrants adjustment to the Polar Code, say experts in a new paper published in the journal Nature.

“The Arctic’s extreme environmental conditions and remoteness make it a complex and dynamic environment for maritime operators,” the paper says. “We find that Arctic shipping has grown by seven per year over the past decade, despite the hazardous weather and sea-ice conditions that pose risks to vessels operating in the region.”

Rapid growth in Arctic shipping

In Arctic is warming more than the rest of the planet, and in some places, four times faster than the rest of the world.

The reduction of sea ice extent has made swaths of Arctic waters increasingly accessible for ship traffic. But the accessibility does not guarantee easy or safe traversal, as unpredictable ice conditions and volatile weather still make transportation through Arctic waters challenging.

To do the study, the researchers, all based at Norwegian institutions, focused on pan-Arctic vessel traffic using 10 years of satellite data from the Automatic Identification System (AIS) that’s used to track ships.

“In order to highlight important gaps in this definition of hazardous conditions we demonstrate the growing level of activities under metocean conditions that pose potential challenges for maritime operations,” the paper said.

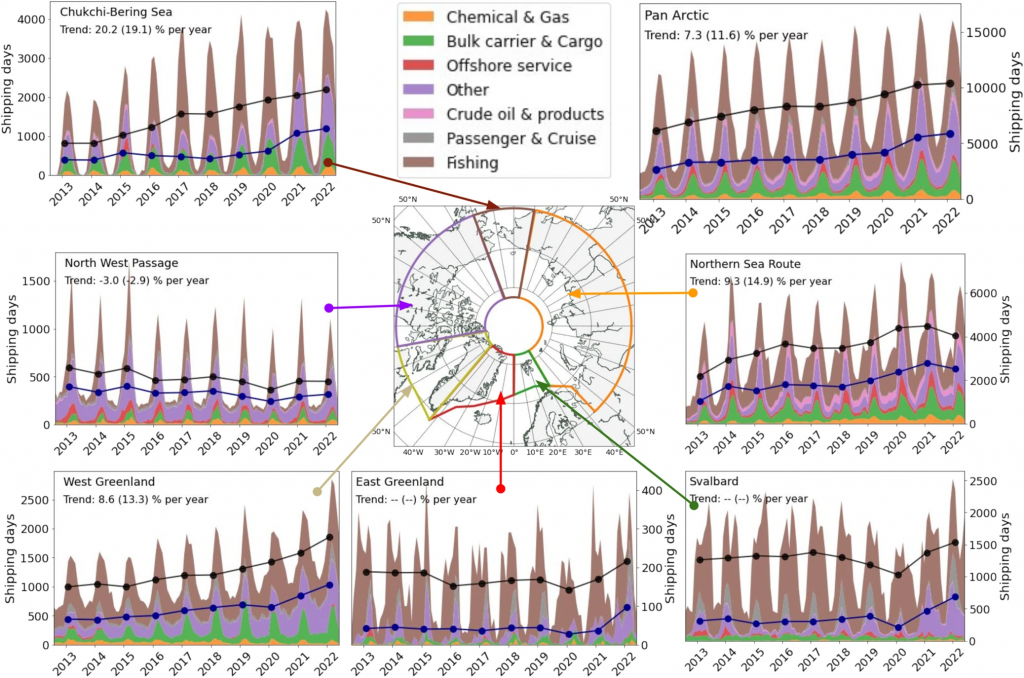

The data showed that four areas saw the largest number of shipping days: the Northern Sea Route (NSR) over Russia, the Chukchi-Bering Sea, West Greenland (including the Hudson Strait areas), and Svalbard.

The types of ship traffic vary depending on the geographical area, with the NSR a particular standout, with most of the traffic related to energy and mineral resource projects in the Russian Arctic

“Along the NSR, transit navigation became active around 2010 and until 2022 there were in total 502 voyages with no significant increase in time,” the researchers say. “The largest amount of shipping takes place as destination shipping and in total, we observe around 300 to 500 individual ships per month in the waters of the NSR .”

Meanwhile in Canada, shipping traffic along the Northwest Passage is mainly related to the summer sealifts where Arctic communities which have no road access to the southern part of the country are resupplied.

Commercial traffic remains minimal with the majority of vessels crossing the entire Northwest Passage were either icebreakers or pleasure craft.

In Svalbard, maritime traffic is mostly fishing or cruise related.

The increase of maritime traffic in the Bering and Chukchi Seas was related to fishing in the period from 2013-2020. From 2020-2022 the rise in ship traffic fell in the category of “other” or bulk carrier and cargo.

Does the Polar Code need to be revisited?

The International Maritime Organization’s International Code for Ships Operating in Polar Waters ( known colloquially as the “Polar Code”) came into force on January 1, 2017 in response to concerns around increased shipping in the world’s circumpolar regions.

Under the code, ships are classified depending on the sea ice conditions the vessel is expected to encounter and must be certified.

In addition, vessel operators are required to spell out how they will tackle and avoid dangerous ice conditions and temperature hazards.

But the researchers say the code needs to be tweaked to keep up with emerging Arctic shipping trends which includes the move from seasonal shipping to year-round traffic, especially in winter when ice and weather can be more dynamic.

“We find that during the winter-spring navigation period, where the minimum number of shipping days is observed, the numbers increase from 2 thousand shipping days in 2013 to about 5 thousand shipping days per month in 2022,” the paper said.

“This change is dominated by the strong increase of winter-spring season activities in the waters of the NSR, where the number of shipping days roughly tripled from a few hundred shipping days in 2013 to more than 1500 in 2022 due to the establishment of the Liquefied Natural Gas (LNG) and oil projects.”

The paper makes three main recommendations for modifying the code:

- expand the hazardous conditions covered to include things like wind, waves and visibility that affect ice conditions

- require vessels to use real-time monitoring instead of mostly relying on historical climate data to gauge risk

- require vessels to use existing international services like the Worldwide Met-Ocean Information and Warning Service (WWMIWS), which gives forecasts and warnings on things like weather, waves, and sea ice conditions

“There is a clear disconnect between the Polar Code guidelines for informed planning and the efficient use of weather and sea-ice information infrastructure that aims to support maritime navigation,” the paper said.

“This constrains the practical value of the Polar Code and arguably compounds operational risks. The continued high demands on weather and sea-ice information services are thus warranted and such services should form an essential element of the regulatory system.”

Related stories from around the North:

Canada: Canada comes out in favour of heavy fuel oil ban in Arctic, Eye on the Arctic

Finland: Finland investigates oil leak risks from Baltic Sea shipwrecks, Yle News

Greenland: Stranded cruise ship pulled free at high tide in Greenland, the Associated Press

Iceland: Iceland to restrict heavy fuel oil use in territorial waters, Eye on the Arctic

Norway: LNG-reloading operations end in Norway’s Arctic waters, The Independent Barents Observer

Russia: Shipping figures rising on Russia’s Northern Sea Route, The Independent Barents Observer

United States: Carnival Corporation ships switch to cleaner fuel on Arctic cruises, Radio Canada International