Fresh water is an absolute necessity of life, and is increasingly becoming a concern. Canada has one of the largest freshwater reserves in the world, much of it spread across northern sections of the country.

However little is known about its vulnerability to climate change and human activity. A good percentage of the reserves are in the permafrost in the subarctic and Arctic.

William Quinton has been studying the hydrology cycle in the subarctic at the edge of the permafrost at a place called Scotty Creek in the Northwest Territories.

He is Associate Professor & Canada Research Chair in Cold Regions Hydrology Department of Geography and Environmental Studies Wilfrid Laurier University, in Waterloo, Ontario.

Listen

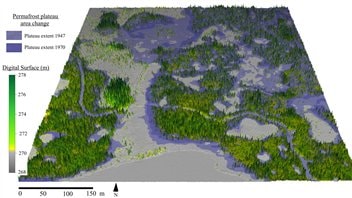

During the years Dr Quinton and his team have been studying the hydrological cycle, they noticed the region where they were studying was quickly changing.

The areas of permafrost were experiencing substantial thawing, and along with them, the forested area which only exists above permafrost in the region.

The permafrost beneath the ground is at a temperature only fractionally below freezing, and as the warming trend increases in the north, it penetrates further into the ground and permafrost thaws.

As the water melts out of the icy earth, the earth sinks and the depressions fill with water which kills the trees. The result is that forested areas recede year after year as more bogs and channel fens replace them.

Dr Quinton notes that climate change is having a much more dramatic effect in the north, than in lower latitudes, and in some places the edge of the permafrost is receding at a rate of a metre per year.

He adds that their research camps have had to be moved several times over the years as the permafrost, which supports a stable surface, thaws, sinks, and the area becomes flooded.

Along with the changes to the extent of forest cover, and the actual composition of the forests, the melting permafrost also has the potential to alter other key aspects of ecosystems.

These include things like runoff and snowcover, biodiversity, and habitat for keystone species.

Other changes include surface-atmosphere interactions including greenhouse gas fluxes, forest fire regimes and the quantity and quality of water flows to downstream ecosystems and the Arctic Ocean.

Local communities have also told researchers that typical trapping seasons have changed dramatically as they have to wait much later into the season before the ground freezes thoroughly in winter enabling them to walk without sinking as they set and retrieve traps. It also makes snowmobile travel more hazardous.

Even NASA has become involved in the widened scope of the research in correlating satellite and high-level imaging with research findings on the ground by both Canadian researchers and other visiting scientists.

Dr Quinton says there is a great deal of new and important research being performed by this wide variety of scientists from differing fields who visit the camp.

He adds while their research is extremely interesting, there is also a deep concern among the scientists about the rapid pace of the change and the uncertainty of what these changes will mean.

He says the research being conducted by Laurier University researchers and the many scientist working in the north is therefore extremely important as they work towards a better understanding of the highly complex interactions and feedbacks among climate, water, biogeochemistry, and the ecology of subarctic ecosystems.

For reasons beyond our control, and for an undetermined period of time, our comment section is now closed. However, our social networks remain open to your contributions.