Proponents of development in the far north, often mining, claim it will bring needed employment and money to the region.

While this is true, there are also unexpected social drawbacks for indigenous communities, especially for Inuit women.

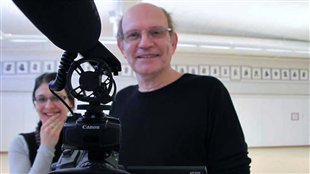

Professor Frank Tester, graduate student Karina Czyzewski and Pauktuutit (the national Inuit Women’s Organization) recently produced a report on the effects of a big mine on the women of the hamlet of Baker Lake.

Tester is a professor in the School of Social Work at the University of British Columbia with years of experience working in the Arctic.

ListenThe Meadowbank gold mine is located about 110 km north of the hamlet of Baker Lake, locally known as Qamani’tuaq, with a population of about 1,700.

The recently released report is entitled ,“The Impact of Resource Extraction on Inuit Women and Families in Qamani’tuaq, Nunavut Territory”

As of December 2012, the Inuit workforce represented about 25 per cent of the approximately 550 workers at Meadowbank. About half of the Inuit workers were women.

While it is true that the mine has provided employment and needed money into the community, it has also changed lifestyles.

Long absences due to the work schedule are something that the Inuit workers and families have virtually no experience with. Workers spend two weeks away, and then two weeks at home.

Combined with an increase in the use of drugs and alcohol – made possible by money and employment – this work schedule has contributed to jealousies and sometimes to violence directed at women staying at home while their partners work at the mine, or the women who work at the mine away from home.

The culture of a mining camp also means there have been cases of rape, usually not reported to officials because of fears of reprisals at work or at home, and a potential loss of the job.

While proponents emphasize that the mine will lead to skilled job training, most of the women are on temporary contracts as janitors, laundry, or kitchen staff. Agnico-Eagle, the mining company, has however, made every effort to train women who are interested as drivers of huge trucks carrying ore to the crusher.

Because of the absences of parents, children are too often left unsupervised. Researchers noted that absence from school increased when one or both parents were away working.

The Inuit women report that the mine has brought blessings in increased employment and money but with it, this increase in violence, discrimination, substance abuse and so on, which has led to breakdowns in family relationships.

There are other less obvious stresses in the community as well. New trucks, ATVs and better dressed children are seen in the community thanks to the influx of money, but that money is not distributed equally, which creates certain tensions in a community where traditionally things like food and equipment have been shared.

Most of the women participating in the workshops and questioned about the mine’s affect upon their lives, said they wanted to see more benefits for the whole community rather than for certain individuals.

As part of the Inuit impact and benefit agreement between the mine owners and the Kivalliq Inuit Association, a Community Economic Development Fund was created.

This was supposed to fund sustainable alternatives to mine employment, and yet though the mine is already halfway through its expected life, there has been no application process to access the funds. Practically no money has been spent on meeting the needs of women in the community or on future employment creation after the mine closes. Questions remain about where royalty payments to Inuit organizations, benefiting from the presence of the mine, are being spent

One of the report’s recommendations is that the Kivalliq Inuit Association put the community development fund in place as soon as possible.

The researchers note that Inuit women want more involvement in the negotiations and planning related to mining, in a community where the possibility of more mines being developed in the region is a reality

For reasons beyond our control, and for an undetermined period of time, our comment section is now closed. However, our social networks remain open to your contributions.