Score a hard-won victory for British Columbia civil libertarians, a win that likely will have wide ramifications and repercussions across Canada.

After years of dissembling and bobbing and weaving around the issue, Vancouver police finally admitted on Wednesday that they used a controversial mass-surveillance device during a suspected abduction case nine years ago.

The admission follows years of back and forth between the police and the British Columbia Civil Liberties Association and other civil society groups that has been pushing relentlessly for full disclosure on the matter.

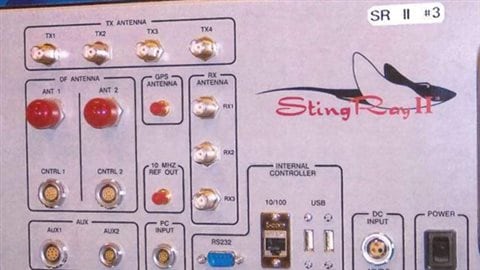

Prior to Wednesday’s admission, Vancouver police denied having any records on the use of the RCMP’s so-called StingRay device, which tricks mobile devices into connecting to it by mimicking a cellular communications tower, allowing police to–at a minimum–access geo-location information and sometimes collect content data.

Vancouver police Const. Brian Montague now says the device was used “in 2007 as an investigative tool to support a VPD suspected abduction case that is now an investigation into a possible homicide.”

Montague said the StingRay was used to locate a specific cellphone owned by the person who may have been abducted.

The police did not get access to any of the data that was collected, Montague said, adding that he could not clarify any further details because the investigation is continuing.

The problem for civil libertarians is that the StingRray intercepts personal information indiscriminately, capturing every cellphone user in the vicinity.

And therein lies most of the rub.

Civil libertarians want to know what happens to the data on calls not connected with a police investigation–calls made by people minding their own business.

Micheal Vonn is policy director of the BCCLA and has been in the forefront of the fight with the Vancouver police.

She says the lack of paper trail for the police department’s use of the StingRay and Wednesday’s admission raise serious legal and public accountability issues.

Safeguards are needed, she says, to protect civil rights.

For Vonn’s take on the week’s events and what they may mean for civil liberties in both British Columbia and Canada, I spoke by phone with her in Vancouver on Thursday.

Listen

For reasons beyond our control, and for an undetermined period of time, our comment section is now closed. However, our social networks remain open to your contributions.