Roughly 120 years ago, Canada was starting to feel the effects of an international social upheaval. Women around the world were demanding the right to vote in elections.

Although there had been stirrings of a women’s voting movement long before, it really began to gain momentum starting in Berlin in 1904. From there the demand for equal voting rights for women, suffrage, had begun to spread internationally.

Berlin poster to get women to come out to a “Women’s Day” suffrage event in March 1914. (wiki Commons)

While some progress for women’s suffrage had been made in Australia, New Zealand and several smaller jurisdictions, including in Toronto municipal affairs, voting in Canada, like many other democracies in the late 1800’s and early 1900’s was an affair reserved for men.

In Winnipeg, Mrs Nellie McClung who had long advocated for social reforms in western Canada, formed a group called the Women’s Political Equality League.

“Give us our due!”

Starting in 1914, her group had presented petitions to the provincial government for the right to vote. She said at the time the delegation had come not to beg for a favour but to obtain simple justice. “Have we not the brains to think? Hands to work? Hearts to feel? And lives to live?” she demanded. “Do we not bear our part in citizenship? Do we not help build the Empire? Give us our due!

The government rejected the petitions and the idea of women’s suffrage.

Nellie McClung pictured in January 1916. She championed women’s suffrage in Manitoba and later was involved in a federal case to have women legally declared as “persons” and eligible to hold public office (via CBC)

McClung then staged a very successful theatrical piece which presented a mock parliament in which the male/female roles were reversed and female politicians with McClung playing the role of the Manitoba Premier debated whether men should get the vote. The play was popular and ticket sales helped finance the suffrage movement.

The Winnipeg Telegram of Jan 29th 1914 reported: “From the standpoint of an entertainment, it was excellent and few burlesques or light comedy productions have ever met with a heartier response than last night’s burlesque on the system of government as it exists today”.

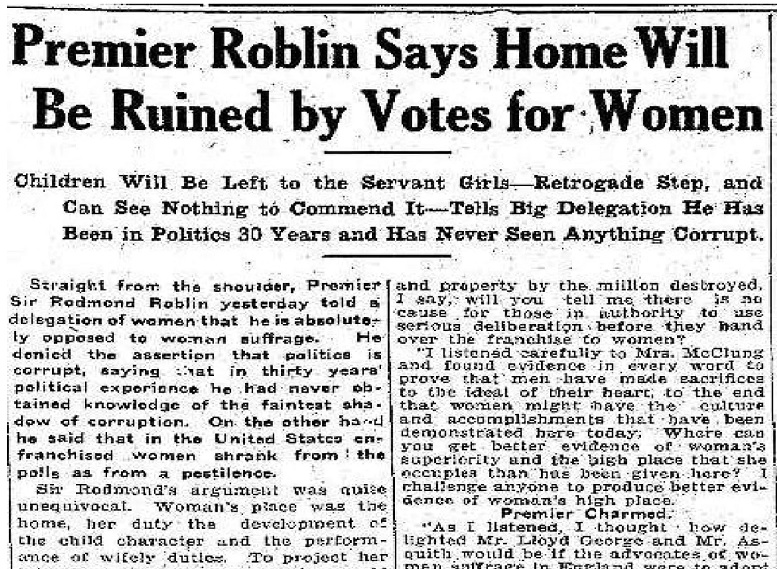

A Jan. 28, 1914, newspaper clipping from the Manitoba Free Press details the strong rebuke the premier offered after he was confronted by women’s suffragists. “Sir Rodman’s argument was quite unequivocal. Women’s place was the home, her duty the development of the child character and the performance of wifely duties” (newspaperarchives.com)

With the outbreak of the First World War in 1914, women had been taking up positions in factories and offices doing work previously only done by men, breaking a previously impossible work barrier. The arguments against women’s suffrage began to be whittled away.

Then in 1915 the provincial government that had rejected suffrage was defeated.

With the Manitoba government she had campaigned for had won the election, another large petition was presented on Jan 26th, 1916, and with so many names, they were obliged to table it for a vote on the 27th and it passed on this date, January 28th, 1916.

Thus Manitoba became the first province to allow women the right to vote in provincial elections.

Other jurisdictions soon followed. Women’s suffrage came the same year in Saskatchewan on March 14, and Alberta on April 19. British Columbia followed a year later on April 5, 1917, then Ontario a week later on the 12th. Nova Scotia changed its laws in April 1918, and New Brunswick in April 1919, and Prince Edward Island in 1922.

The federal wall began to crack under the pressure as well.

n 1917, with so many men fighting overseas and so many women now in the work force further increasing their desire to have a voice, the federal government finally agreed to the increasingly powerful suffragette movement. In September it passed the “Wartime Elections Act” granting the vote to the wives, mothers and sisters of serving soldiers, as well as women serving in the armed forces.

This “half-measure” did not stop the pressure on the federal government, thus in 1918, all female “citizens” aged 21 and over became eligible to vote in federal elections, with the proviso they were “aged 21 or older, not alien-born and met property requirements in provinces where they exist.” In July 1919 women gained the complementary right to stand for the House of Commons, but still could not be appointed to the Senate, as they were deemed not to be “persons” eligible for senate position under the law.

McClung continued her suffrage campaign when, along with Irene Parlby, Henrietta Muir Edwards, Emily Murphy and Louise McKinney- who together became known as the “Famous Five”, they sent a petition to Ottawa to clarify the term “Persons” in Section 24 of the British North America Act 1867.

Clockwise from top left: The Famous Five are Louise McKinney, Nellie McClung, Henrietta Muir Edwards, group shot, Irene Parlby and Emily Murphy. Because of their efforts, on October 18, 1929, the Privy Council declared in the famous “Person’s Case of 1929” that women were persons and thus eligible to hold any appointed or elected office. (Glenbow Archives)

The petition sent in 1927, was defined in a Supreme Court decision in 1928 which declared that women were not “persons” under the law and could not be appointed to the Senate.

That decision was appealed and finally overturned once and for all by the British Judicial Committee of the Privy Council on 18 October 1929, which at that time still held the final word over Canadian law.

Statues of the “Famous Five” on Parliament Hill, Ottawa. These five Alberta women, helped to complete the work of women’s suffrage in Canada through their challenge to be defined as “persons” under law in 1927-29.. Other statues dedicated to the women exist in Manitoba and elsewhere Photo Credit: via CBC

Only Quebec resists

It should be noted that the in the mainly French-speaking province of Quebec, the Catholic church and politicians and many citizens were against women’s suffrage, and fought against it for years.

“The entry of women into politics, even if only by suffrage, would be a misfortune for our province. Nothing justifies it, neither natural law nor the social interest; the authorities in Rome approve of our views, which are those of our entire episcopate.” (translated) wrote Cardinal Bégin as cited in a Quebec historical magazine in 1990 ( Cap-aux-Diamants, no 21, spring 1990, p. 23).

Also cited in the same edition of the historical magazine was a comment by Henri Bourassa who founded the newspaper Le Devoir, “…French-Canadian women risk becoming “public women”, and “veritable women-men, hybrids that would destroy women-mothers and women-women.”

“The argument of the similarity with the other provinces is cited, as if for some, progress consists of aping what others do. Québec has its traditions, its customs and they are its strength and its greatness. Were this bill to pass, women would resemble a star having left its orbit” said L-A. Giroux, a legislative councillor (Wellington), on April 25,1940, recorded in the debates at the Legislative Assembly.

Faced with this strong opposition, women gained the right to vote in Quebec elections only in April 1940.

For reasons beyond our control, and for an undetermined period of time, our comment section is now closed. However, our social networks remain open to your contributions.