As demonstrators protest COVID-19 restrictions across the country, other Canadians continue to scratch their heads trying to figure out just what the heck is going on.

“It’s not like anybody’s asking them to storm the beaches of Normandy,” say many.

“All people are being asked to do is wear a mask and socially distance.

“What’s the problem?”

Explanations abound.

Protesters gather outside the Ontario Legislature in Toronto, as they demonstrate against numerous issues relating to the COVID-19 pandemic on Saturday, May 16. (THE CANADIAN PRESS/Chris Young)

A study published in May at Carleton University indicated 46 per cent of Canadians believed at least one of four unfounded COVID-19 theories: the virus was engineered in a Chinese lab; the virus is being spread to cover up the effects of 5G wireless technology; drugs such as hydroxychloroquine can cure COVID-19 patients; or rinsing your nose with a saline solution can protect you from infection.

“But why?” many ask.

In an interview with Nancy Carlson, host of CBC Edmonton’s News at 6, following the release of the Carleton findings, University of Alberta professor Timothy Caulfield noted: “When things are uncertain, when there’s a lot of fear, when the science is still moving, people are more likely to believe conspiracy theories.

“That’s certainly the situation that we have now.”

Now, a new study adds another piece to the puzzle.

It found that the more someone relies on social media to learn about COVID-19, the more likely they are to be exposed to misinformation and to believe it, and to disregard physical distancing and other public health guidelines.

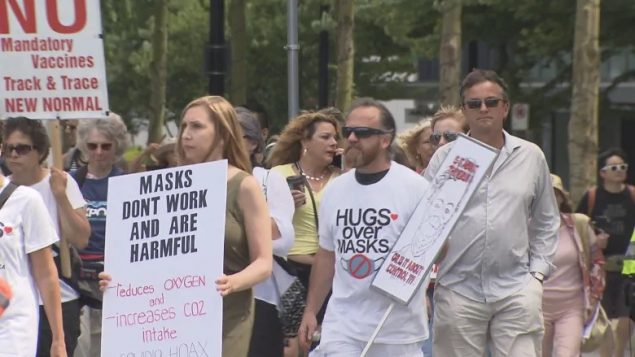

About 50 people attended an anti-mask protest at Jack Poole Plaza in Vancouver on July 19. (CBC)

“We thus draw a clear link from misinformation circulating on social media, notably Twitter, to behaviours and attitudes that potentially magnify the scale and lethality of COVID-19,” the study reads.

In an article published Monday, Aengus Bridgman, the study’s co-author, told Jillian Kestler-D’Amours of The Canadian Press that about 16 per cent of Canadians use social media as their primary source of information on the virus.

“I think that people should be enormously concerned,” Bridgman, a PhD candidate in political science at McGill University, told Kesler-D’Amours.

Bridgman says that while some right-wing groups in Canada are pushing COVID-19 falsehoods, people across the political spectrum are vulnerable to them.

“This is a Canadian challenge,” he says.

“People across levels of education, across age groupings, across political ideas, all are susceptible to misinformation online. This is not a phenomenon that is unique to a particular community.”

With files from Jillian Kestler-D’Amours of The Canadian Press

For reasons beyond our control, and for an undetermined period of time, our comment section is now closed. However, our social networks remain open to your contributions.