At least that’s how most Canadians felt when a special Commission handed down it’s decision on the Alaska panhandle dispute.

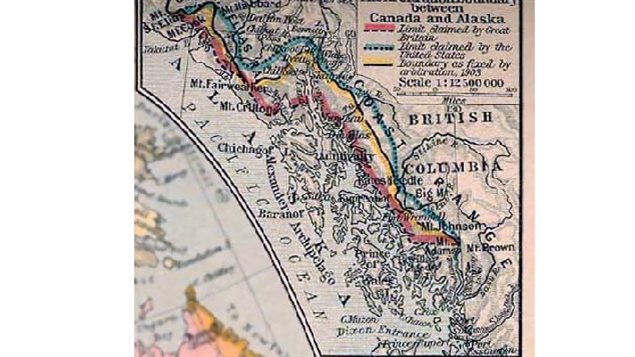

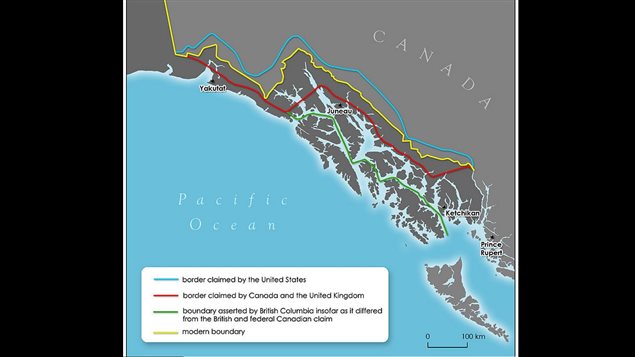

On October 20 1903, the Commission of three Americans, two Canadians, and one Briton, handed down it’s decision on the long-standing border dispute between Canada and the US regarding the actual border between Alaska and British Columbia.

In the early 1800’s Alaska belonged to Russia, and Canada belonged to Britain, and America was already threatening to expand northward.

In 1824 the Russo American agreement stated that no American colony would be established along the west coast or island north of 54°40′, and no Russian colony south of that point.

Then the Anglo-Russian Convention of 1825 chose that same point to vaguely define Russian possession along the coast although it was more of a trading agreement between a Russian company and the Hudsons Bay Company (HBC) and made no reference to sovereignty.

In the US, there was a strong movement to expand into what was still HBC controlled territory, up to 54-40 and the slogan “54-40 or fight” was often heard.

To protect it’s own interests against American expansion pressure, and an influx of Americans’ into small gold rushes, the colony of British Columbia was created in 1858. By 1867 however, it was faced with remaining as a British colony, joining Canada, or being annexed by the US. In Britain, the feeling to that point was not very strong to have it remain as a part of the Empire “The Times” and one point stating, “ British Columbia is a long way off. . . . With the exception of a limited official class it receives few immigrants from England, and a large proportion of its inhabitants consists of citizens of the United States who have entered it from the south”

However when the US bought Alaska from Russia in 1867, Britain realized that having B.C within its sphere of influence would be beneficial to its interests in the Pacific.

B.C. also had its own verision of its territory as related to the Alaska panhandle, when it joined Canadian Confederation in 1871 and pushed for a survey as Russian maps of 1825 showed the Russians and now Americans having more territory than it would seem according to the treaties.

In 1872 the US rejected surveys as being too expensive and the US-Canada/BC dispute simmered.

In 1898, the Klondike gold rush was at its height, with thousands of mostly American miners turning the region from a remote almost uninhabited wilderness without importance into a bustling hive of activity and commercial importance. That year a joint high-commission worked out a boundary compromise, but American interests objected so strongly the compromise was dropped.

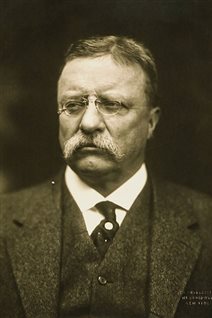

In 1901, the US under President Teddy Roosevelt began applying his policy of “speak softly but carry a big stick”. Canadian shipments were being held up, and Canadians in Alaska began experiencing harassment and denial of certain rights.

In 1903 the Hay/Hebert Treaty called for a panel to determine the border. Roosevelt had instructed the three US members to make the “right” decision or he would have to send in the US military, leaving rather clear doubt as to the impartiality of the US side.

The two Canadian members, (and all Canadians) meanwhile presumed they would get British support in return for Canada’s contribution in Britain’s Boer War.

Britain however was more concerned about creating good relations with the US, and the British member sided with the US in a decision handed down October 20, 1903.

The British position shocked and angered Canadians who considered this a betrayal.

It was also another major step towards a sentiment of Canadian identity separate from that of Britian.

In the end, the final decision was more of a compromise between the two original positions, but that didn’t assuage Canadian opinion.

One part of the decision involved the fact that Canada had not asserted Canadian sovereignty in the region whereas the Americans had established a presence.

As a result Canada sent the Northwest Mounted Police to other areas the might face similar challenges such as Herschel Island in the Arctic.

It also resulted in a perception that Canada could not rely on Britain to protect its interests and thus led eventually to the creation of Canada’s Department of External Affairs in 1909

For reasons beyond our control, and for an undetermined period of time, our comment section is now closed. However, our social networks remain open to your contributions.