A unique project is taking place in Canada to better understand ancient religious chants, and how the medieval mind worked. Because the music was not written, the monks would have to memorize up to 80 hours or more worth of all the liturgical melodies.

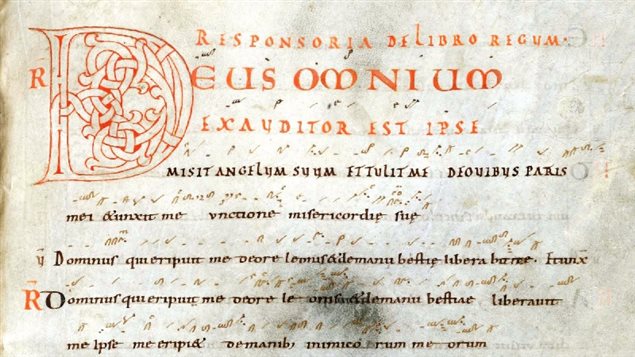

At some point prior to the year 1000, the first code was developed in this completely oral tradition in order to help remind monks of the melodies and to ensure the same music was being sung in various monasteries. These notations above the Latin text are called neumes.

Kate Helsen (PhD) , an assistant musicology professor at Western University’s Don Wright Faculty of Music at the University of Western Ontario. She leads the Optical Neume Recognition Project. *chants by group Psallentes-Hendrik Vanden Abeele- Belgium

Listen

Professor Helsen says that although there are several other institutions and scholars around the world studying ancient music and neumes, to the best of her knowledge no-one else is working on a similar effort, making this a very unique Canadian effort combining handwriting analysis software to images of thousand-year-old musical notation.

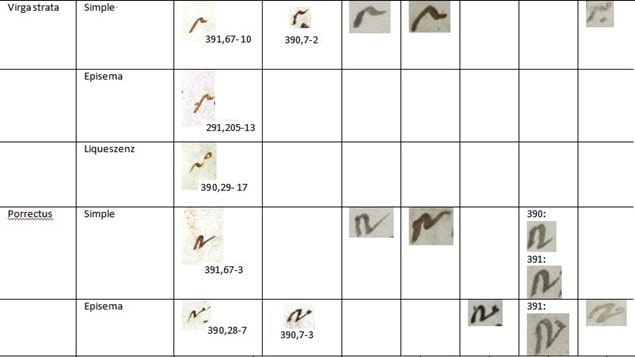

Because the neumes do not indicate pitch, one might be fooled into thinking they are simple, but in fact there are a vast number of them and it is a complex and sophisticated system.

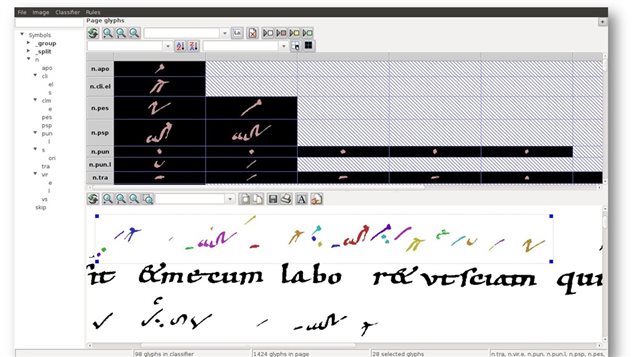

The project is developing a computer language to help researchers decipher the complex code to better understand how the music was actually sung and memorized faithfully for generations.

“Basically, we are mining these melodies for a better understanding of how the brain breaks down, thinks about and reconstructs melody year after year after year in a monastic context because that’s what was important to them, to sing the same prayer, the same way every year”, says professor Helsen.

Much like deciphering a secret spy code, the programme identifies each neume on a digital scan of a page from a historic book of medieval chant, cataloguing each one and ranking them in order of graphic similarity while additionally storing data about how often a particular neume appears in specific combinations thereby creating a virtual ‘dictionary’ of neume signs.

This greatly speeds up the work of researchers of ancient music.

The Optical Neume Recognition Project, currently funded by Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council (SSHRC), is part of a larger research collaboration known as Single Interface for Music Score Searching and Analysis (SIMSSA) led by Ichiro Fujinaga at McGill University in Montreal. It seeks to create a single clearinghouse for digital images of musical scores, both printed and handwritten, around the world.

For reasons beyond our control, and for an undetermined period of time, our comment section is now closed. However, our social networks remain open to your contributions.