Jean-Jacques Simon is worried about vaccination.

The Canadian spokesperson for the United Nations children’s agency in Bangladesh needs to find money to vaccinate hundreds of thousands of Rohingya children who have fled a vicious campaign of ethnic cleansing in their native Myanmar.

UNICEF is one of several humanitarian agencies trying to cope with the influx of more than 625,000 Rohingya refugees into one of the least developed parts of Bangladesh, an area called Cox’s Bazar, on the border with Myanmar.

With the 300,000 Rohingyas who had fled Myanmar, also known as Burma, during the previous bouts of violence there are now about a million refugees scattered in makeshift camps all around Cox’s Bazar.

‘Vaccinate, vaccinate, vaccinate’

Most them are women and children who have survived and witnessed unimaginable violence as their villages in Myanmar were attacked during a violent crackdown by Burmese security forces and vigilante groups in retribution for attacks by Rohingya militants on 30 police stations and army outposts in August.

Now, huddled in flimsy bamboo and plastic tents set in farmers’ fields or on exposed hilltops with little access to clean water and proper sanitation these Rohingya refugees are facing the threat of deadly but preventable communicable diseases.

Thus the need to vaccinate.

“These days it’s pretty much about vaccination because we have a diphtheria crisis in the camps,” Simon told Radio Canada International.

More than 700 children under the age of 15 have been affected with 10 fatalities so far, said Simon who has been dispatched to Canada from Bangladesh for meetings with Canadian officials in Ottawa in hopes of securing more funding.

“It’s a big issue for us,” said Simon. “It’s not the first time we have such a crisis, obviously over the last three months and a half, when you have 650,000 people coming in, mostly children, you have such issues. You have to vaccinate, vaccinate, vaccinate.”

Most of the refugees had never been vaccinated in Myanmar, where they were denied citizenship and basic rights even before the current outbreak of violence that the UN has called “a textbook example of ethnic cleansing.”

‘Pure horror’

“They were not allowed to have proper health services, they didn’t have education, their parents weren’t allowed to work,” Simon said. “So what really gave this population all kinds of issues especially when they crossed the border, they were traumatized because many of their parents, siblings, sisters were either killed or raped, their houses were burnt.”

The stories the children tell or draw on paper when visiting special learning centres set up by UNICEF can be overwhelming even for grizzled humanitarian workers like Simon who has over the years served in various capacities in Haiti, the Democratic Republic of Congo and Burundi.

“It’s pure horror,” Simon said.

Focus on host communities

The influx of so many people into one of the poorest regions of Bangladesh, itself not a very prosperous country, is causing all kinds of issues for the local communities in Cox’s Bazar, he said.

“That’s why we now focusing on what we call the host communities, so that the host communities, the Bangladeshis, don’t feel threatened by the Rohingya influx, don’t feel threatened that we offer services, support to the Rohingya and not them,” Simon said. “Now you have to have to focus on the host communities as well, so you don’t have clashes between the two communities because that would be really awful.”

The crisis could last several months if not years, Simon warned.

“A million people is a lot of people,” Simon said. “Imagine, it’s a big city in Canada, which is built in the matter of three months and a half.

“Imagine having an influx of a million people in Canada, well you need to organize yourselves. You need to properly offer services and you need to have structures like latrines, like clean drinking water, like vaccination campaigns, like medical centres, like schools and etc.”

That’s in the making now – not at the same level as it would exist in Canada – but it is happening, Simon said.

Light at the end of the tunnel

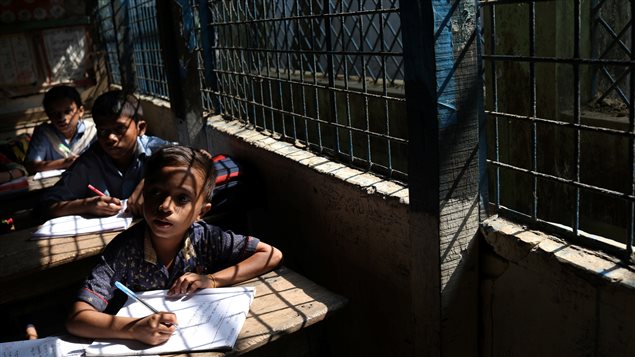

UNICEF has to create the conditions for the Rohingya children to go to school, something most of them were unable to do in Myanmar.

“We know have learning centres which allow 33,000 Rohingya students to go to school,” Simon said. “A learning centre is a bamboo structure with plastic sheeting but it still makes a big difference for many of these children: they are, for one, protected, they learn, they are together and they see some sort of light at the end of the tunnel.”

There are also huge issues facing the agency in making sure that girls and young women are not sexually exploited and sold off to prostitution rings to be trafficked all around the country, that their health needs are met, that they receive proper education and vocational training, Simon said.

“We’ve seen many cases of Rohingya girls ending up in prostitution rings across the country, not only in Cox’s Bazar,” Simon said.

“We need to support young girls who were raped who are fearful of getting married off by their parents between the age of 10 and 14, because that’s the reality as well,” he added.

Funding gap

To do all these programs UNICEF needs money.

The UN has appealed for $434 million, including some $76.1 million for UNICEF to address the immediate needs of newly-arrived Rohingya children, as well as those who arrived before the recent influx, and children from vulnerable host communities.

However, a ministerial-level pledging conference held in Geneva on Oct. 23 raised only $344 million.

This means that only 65 to 70 per cent of programs have been funded, Simon said.

For reasons beyond our control, and for an undetermined period of time, our comment section is now closed. However, our social networks remain open to your contributions.