Moose are an iconic animal of Canadian (and northern U.S) forests and they are big, with the males weighing 500 kg or more and growing huge impressive antlers.

But they are being threatened by something tiny. It’s a parasite known as the winter tick.

Slightly different and slightly bigger than other ticks, such as the black-legged tick, that can pose severe health hazards to humans including Lyme disease. Winter ticks affect mostly moose.

An engorged winter tick showing relative size (CBC News- U Laval study)

Scientists are now studying moose populations in Quebec and New Brunswick to determine how the moose change their behaviour when infested. They also are looking at the survival rate of ticks and their spread. The ticks are a bloodsucking parasite and though moose are big animals, literally tens of thousands of the parasites can seriously weaken the animals, reducing their survival.

A similar study in the U.S states of New Hampshire and Maine found up to 70 per cent calf mortality due to tick infestations literally in some cases sucking so much blood the animal dies.

A so-called “ghost moose’ with whitish skin showing where the dark fur has been rubbed off as the animal tries to rid itself of itching ticks This leads to health problems for the animal and exposes it to cold (N.H. Fish and Game Dept)

Climate change and ticks.

Scientists also note that climate change is allowing the winter tick (and other ticks) to expand further and further northward as shorter, milder winters and less snowfall fail to kill them off in large numbers.

As the ticks accumulate on the animal and irritate the skin, moose will try to scratch them off by rubbing hard against trees, but in doing so also often scrape off their own fur leaving them vulnerable to cold or causing open wounds prone to infection.

U Laval scientists pull back the fur on a sedated moose to show the high number of ticks. Scientist have found infestations of up to 70-80 thousand ticks on a single animal, They also say climate change means higher tick survival through winter and a range expanding northward. (CBC News)

The five year Canadian study, involved finding moose by helicopter then immobilizing them safely with a net fired from the aircraft. The number of ticks are counted on a patch of skin and estimated for the animal. A tracking collar is then attached that monitors the animals movements. This determines behaviour comparisons between heavily infested moose with those having little infestation.

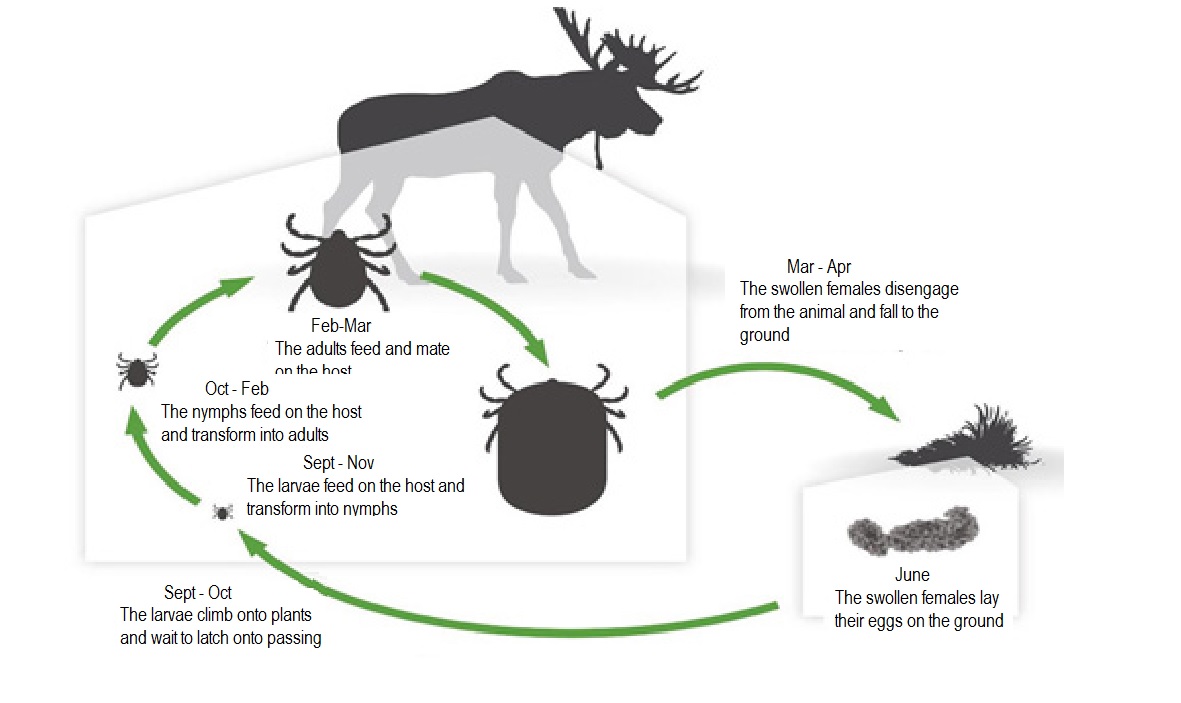

Lifecycle of winter tick (Forets, Faune, et Parcs Quebec)

The Quebec study by the University of Laval in collaboration with the University of New Brunswick also includes J.D. Irving Foresty. A representative said the trees they plant today will be harvested in 40 years, but by then the climate will have changed dramatically so they are interested in studies of animal behaviour in their forests which will change their own forest management practices.

Additional information-sources

- CBC: K. Hounsell: Feb 6/20: Thousands of blood-sucking ticks found on bodies of Canadian moose (+video report)

- The Atlantic: D Dobbs: Feb 21/19: Climate Change Enters Its Blood-Sucking Phase

- Canadian Journal of Zoology: Jul 12/28: Mortality assessment of moose (Alces alces) calves during successive years of winter tick (Dermacentor albipictus) epizootics in New Hampshire and Maine (USA)

- University of New Brunswick: C.Morris: Sep 27/19: Ghost moose concern NB scientists

- Forets, Faune, et Parcs Quebec: Moose winter tick

For reasons beyond our control, and for an undetermined period of time, our comment section is now closed. However, our social networks remain open to your contributions.