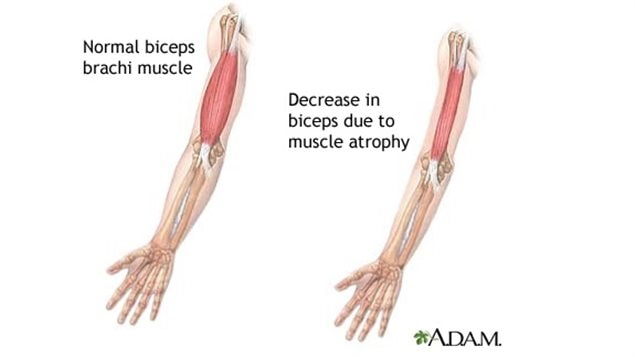

Muscle atrophy, muscle-wasting, or the more technical term cachexia are all relatively interchangeable terms.

It’s when a person begins to lose muscle and becomes increasingly weaker often as a result of a disease or infection such as cancer, HIV or others.

This weakness can reduce the effectiveness of treatment and also certainly the quality of life of those afflicted.

A McGill University and University of Alberta breakthrough after years of research has discovered a key to potentially fighting this syndrome.

Endocrinologist Dr. Simon Wing M.D, is a professor in the Faculty of Medicine at McGill, and the director of Experimental Therapeutics and Metabolism at the Research Institute-McGill University Health Centre in Montreal (RI-MUHC).

Listen

Dr Wing supervised the research which appears in the June online edition and September print edition of the FASEB Journal (Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology),

It seems in our distant evolution, the body developed a defence mechanism when the person was severely ill. In such a state, the person could not seek food, and so the body would use muscle as a source of energy to “feed” the body while fighting the infection.

This defence mechanism is so ingrained that even now when the body is being nourished through such things as intravenous feeding, the wasting still goes on.

The research breakthrough came in identifying the gene -USP19- that appears to be involved in human muscle wasting.

The researchers developed mice with that gene removed (knock-out or KO) and when subjected to typical muscle wasting situations they showed far less muscle loss syndrome, than mice with the gene. The two typical scenarios tested were when the mice were given the hormone cortisol, which can be released in stressful situations like illness or surgery, and the loss of nerve activation resulting in atrophy following a stroke and or when people are weak and bedbound.

“We found that USP19 KO mice were wasting muscle mass more slowly; in other words, inhibiting USP19 was protecting against both causes of muscle wasting,’’ says Dr. Wing. “Our results show there was a very good correlation between the expression of this gene in the human muscle samples and other biomarkers that reflect muscle wasting.’’

In a McGill press release, Dr. Antonio Vigano, director of the cancer rehabilitation program and cachexia clinic at the MUHC said “Cancer patients often present with muscle wasting even prior to their initial cancer diagnosis,’’

He added, “In cancer, cachexia also increases your risk of developing toxicity from chemotherapy and other oncological treatments, such as surgery and radiotherapy. At the McGill Nutrition and Performance Laboratory we specialize in cachexia and sarcopenia. By treating these two pathologic conditions through inhibiting the USP19 gene, at an early, rather than late, stage of the cancer trajectory, not only can we potentially improve the quality of life of patients, but also allow them to better tolerate their oncological treatments, to stay at home for a longer period of time, and to prolong their lives.’’

With this important discovery, research will now continue towards finding a way to block USP-19.

Although Dr Wing says there are still years of research ahead, the discovery could have huge clinical implications, as muscle wasting is associated with all types of cancer and with HIV/AIDS but also with chronic illnesses such rheumatoid arthritis and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease and is also a prominent feature of aging.

This study was supported by the Canadian Institutes of Health Research (CIHR) and the Terry Fox Research Institute (TFRI).

For reasons beyond our control, and for an undetermined period of time, our comment section is now closed. However, our social networks remain open to your contributions.