Forensic scientists have long used chemical and other analyses of hair and teeth to determine such things as diet of an individual, usually for historical purposes. Now researchers at the Arctic Research Centre, Aarhus University in Denmark, are using similar techniques to determine eating habits and health of the hairy ruminants of the high Arctic. They say that muskox diet and reproduction is also is related to climate change.

The study points out that in the tundra ecosystem, the muskox, Ovibos moschatus, plays a key role as one of few large herbivores.

Published in the science journal “PLOS one” on April 20, the study is called. Show Me Your Rump Hair and I Will Tell You What You Ate – The Dietary History of Muskoxen (Ovibos moschatus) Revealed by Sequential Stable Isotope Analysis of Guard Hairs”

The researchers snipped guard hairs from ten animals in Greenland and then by detecting nitrogen isotopes, were able to reconstruct diets over two and a half years.

Nitrogen levels vary according to what the animals eat, or don’t eat.

The animals have to build up and store fat in the summer, for the harsh winter months. A snowy year means less food availability and more reliance on fat reserves.

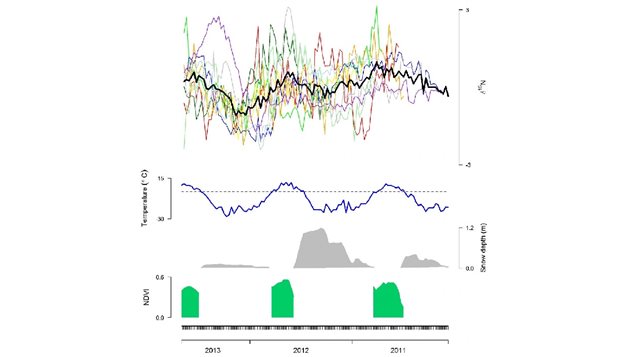

GRAPH ABOVE: Shown in the top is the muskox (Ovibos moschatus) dietary history inferred from the standardized nitrogen isotope ratios (δ15N) in guard hairs from 10 muskox cows and their mean (black line), covering approximately 2.5 years with a temporal resolution of app. 9 days. Below the stable isotope ratios are shown the ambient environmental conditions: Mean air temperature (°C), mean snow depth (m) and meadow productivity (NDVI) from the study area in the 9-day intervals. The guard hair dietary chronology matched the local environmental fluctuations, and included almost three full summer (high δ15N ratios) and winter periods (low δ15N ratios). Compared to summer diets, winter diets exhibit more pronounced inter-annual variation

As the females must have enough reserves for pregnancy, food availability also plays a role in reproduction; with lots of food meaning more calves in spring, and less food meaning fewer or no calves.

The researchers say the study provides a first glimpse at how changing temperatures and snow conditions affect the animal’s diet, and therefore production of calves.

Quoted in Eureka News, lead researcher Jasper Mosbacher says, “With climate changing twice as fast in the Arctic than elsewhere, and with declining muskox populations in the Arctic, understanding how a changing climate is affecting a key species in the Arctic is crucia

Additional information- sources

For reasons beyond our control, and for an undetermined period of time, our comment section is now closed. However, our social networks remain open to your contributions.