Since my first Safe&Sound column on throat singing, I meant to explore Canada’s Indigenous music scene. In Quebec, the most important stakeholder is undoubtedly Musique Nomade, a Montreal-based, non-profit organization dedicated to promoting and producing up-and-coming Indigenous musicians.

Based on the same model as Wapikoni, a mobile studio founded by Quebec filmmaker Manon Barbeau to help Indigenous youth making their own films, Musique Nomade’s first mandate is to bring music literacy and production tools to communities in Quebec.

Since 2011, a mobile team composed of artistic directors, filmmakers, and administrative coordinators has been visiting several Indigenous communities throughout Quebec each summer, helping hundreds of young musicians find their voice, compose, and record their own creations.

As a follow-up to these music creation workshops, Musique Nomade started showcasing its roster of new Indigenous musicians during the Presence Autochtone festival in Montreal, a flagship cultural event dedicated to Canada’s First Nations. After a 20-minute presentation – which often was their first opportunity to perform on stage for an audience – the artists would be introduced to music industry professionals.

In 2017, Musique Nomade then started Nikamotan Mtl, a larger scale outdoor concert at the heart of the Entertainment District which has been offering refreshing crossovers between Indigenous artists and other Canadian musicians. Check out below the music encounter between Montreal’s klezmer-hip hop DJ Socalled and reggae Innu singer Shauit.

Nikamowin, Canada’s Indigenous Spotify

The word soon spread that Musique Nomade was a reliable partner. More artists were calling to invite the mobile studio to give free workshops in their community. Thanks to a domino effect, music collaborations by Musique Nomade expanded from Quebec to New Brunswick and Nova Scotia eastbound, and to Ontario westbound.

To answer the demands of an increasing number of industry members requesting advice on Indigenous artists for their programming, Musique Nomade set up a music streaming and sharing web platform presenting Indigenous music of all styles.

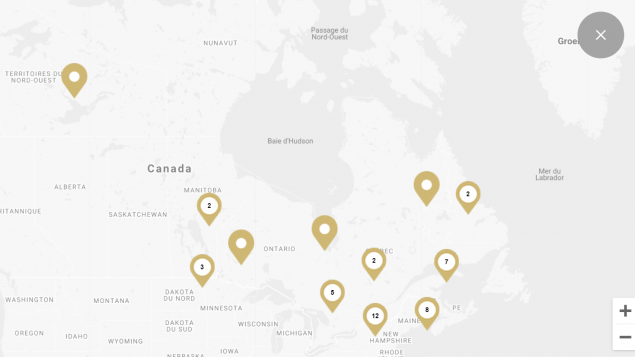

Nikomawin – meaning ‘music’ or ‘song’ in the Atikamekw language – is a unique and valuable research tool that lists about 200 artists according to their nation, language, music genre or the location of their community – Internet users can explore the territory on a geographical map.

Musique Nomade posted a map on its Nikomawin streaming platform to locate the communities of Indigenous artists. (Nikomawin screenshot)

The streaming platform also offers a monthly music playlist, a detailed information sheet about each musician, including photos, video clips and live recordings, as well as the possibility to create your own playlist. A real treasure chest of Native music gems.

Building global bridges

Three Finnish bands from the Sami Nation are featured on the Nikamowin platform. This is the result of fruitful international outreach efforts implemented by Joelle Robillard, Musique Nomade’s artistic director since 2018. She has developed projects in particular with VILDÁ, a female duo she met last year at a WOMEX industry event in Tampere, Finland.

The two members of Vildá, Hildá Länsman and Viivi Maria Saarenkylä, traveled to Montreal to take part in the 2019 Nikamotan edition. Robillard felt a music encounter was possible with two Canadian female artists, Innu Soleil Launière and Geneviève Toupin, aka Willows, a Metis from Manitoba. She contacted the sound engineers Simon and Greg, who opened up their studio to the four women last summer.

The Finnish and Canadian singer-songwriters were given the unique opportunity to create music together during a three-day session that mixed the musical universe, culture and language of each of them. This special moment led to a music documentary called Remember Your Name.

The two music pieces resulting from this energetic and spiritual journey that combines folk music, traditional yoik, accordeon and pop-alternative sounds is accessible on the Nikamowin page of each artist.

Connecting diverse musical genres and Indigenous cultures

The exploration of musical crossovers continued this spring – in March, right before the lockdown – with another residency mixing throat singing and electronic sound effects, by Mohawk and Inuit female musicians.

“At the Nikamotan 2018 edition we witnessed an organic communion between throat singing and electronic music with Sylvia Cloutier and Quantum Tangle and we found it very interesting to explore,” explains Robillard.

She called the Inuit singer Angela Amarualik, whom she had met at the Indigenous Music Award in Winnipeg, and matched her with Kiana Cross, a Mohawk DJ from Kahnawake.

Throat singing being an Inuit practice traditionally performed by two women facing each other, Robillard also included Nancy Angilirq to sing along with Amarualik. Both women come from Igloolik, in Nunavut.

Guiding them in mixing voices and beatmaking was the sound engineer and artistic director Blaise Borboën-Léonard. “The four of them explored for a week and created a mix of beats and textures around the theme of water that reminded me of Moby. We will launch their single this year,” Robillard said.

The provincial TV channel Télé-Québec broadcast a program about this music creation.

A solid foundation for the future

Joelle Robillard recalls that several North American Indigenous folk singers were popular in the 1960s and 70s, but later fell into oblivion. But in First Nations reservations, younger generations remember the heritage of role models such as Philippe McKenzie, who was the first to dare sing in Innu.

“In Quebec’s Innu community of Mani-Utenam, young artists are influenced by Philippe McKenzie, who is considered the pioneer of Innu folk. Many of them still play his songs,” Robillard said.

Saving Indigenous languages

Remember Kashtin ?

Meaning “tornado” in Innu, this band from Mani-Utenam – the same community as Philippe McKenzie – released in 1989 “E uassiuan” (“My childhood”), which immediately became a hit and sold over 200,000 copies worldwide.

Unfortunately, the 1990 Oka crisis in Quebec brought tensions that made it more difficult for Indigenous to sing in their own language and get some airplay on commercial radios.

“It was not a good idea to be an Indian in Quebec at that time … Although we had built a bridge, the (Oka) crisis was bringing us 50 years behind, » recalls Kashtin member Florent Vollant in an interview marking the 30th anniversary of his seminal album.

After Kashtin and Florent Vollant, Quebeckers heard Innu singers such as Shauit. The reggae singer explains in a documentary film that he only spoke French at first and learnt Innu to be able to talk with elders, learn about his roots, and sing in his ancestors’ native tongue.

Since the 2000s, Quebeckers also discovered the popular Inuit singer Elisapie, who sings in inuktitut, the language spoken in northern Quebec and Nunavut. And more recently, New Brunswick opera singer Jeremy Dutcher garnered a lot of media attention in Canada by re-discovering the lost language of his ancestors and singing along with archived recordings of their voices.

Despite an apparent resurgence, Robillard said convincing commercial radios to play Indigenous music remains a challenge. In her opinion, the Canadian Radio-Television and Telecommunications Commission (CRTC) should implement regulations to protect and promote Indigenous languages, just like it did in the early 1970s to support Canadian content.

She hopes the current CRTC review of its policy on Indigenous broadcasting will lead to a stronger support of Indigenous languages.

Read our previous Safe & Sound music columns:

- Orientalys festival brings music to the virtual stage, ‘as if you were there’

- US and Canadian festivals team up for a month of virtual world music shows

- Montreal’s Mural Estival closes the summer with street art and music

- “Fait Vivir”, a road movie about Canadian music gypsies in Colombia

- Music industry delegates meet online at a new global conference in Toronto

- Brazilian artist Diogo Ramos sings his love for Quebec, diversity and freedom

For reasons beyond our control, and for an undetermined period of time, our comment section is now closed. However, our social networks remain open to your contributions.